Uncategorized

Jackson Browne

„A Human Touch“ zum Beispiel: „Everybody get s lonely / Feel like it s all too much / Reaching out for some connections / or maybe just their own reflection / Not everybody finds it / Sometimes all anybody needs / IS A Human Touch“

Es gibt sie noch, die Texte zum aktuellen Zeitgeschehen, sogar musikalisch unterlegt. Ich entdeckte sie im Austin City Limit TV, wo ich mir einen Auftritt von Jackson Browne anschaute. Die Lyrics kommen aus seiner Feder. Er trat mit der Sängerin Leslie Mendelssohn auf, übrigens eine spannende Neuentdeckung für mich. „A Human Touch“ ist ein wunderbar weich gesungenes Lied, sie schrieben und sangen es zusammen für einen Film. Auf dem Programm stand noch ein anderer Song, den Jackson den Kindern von Immigranten gewidmet hat: „The Dreamer“.

Just a child when she crossed the border / To reunite with her father / And with a cruxifix to remind her / She pledged her future to thls land / And does the best she can do / A dónde van los sueños…

Das ist ein Gänsehautsong. JB knüpft an die Traditionen seiner Songwriterfreunde an, die in den 69ern begannen über Proteste, Tod und Kriege zu singen: Bob Dylan, CSNY, Joni und Joan – was für glory times!

Jackson ist ein brillanter Songwriter, ernst und immer mit der Zeit gehend. Er kann aber auch lustig sein, wie er in „Red Neck Friend“ über einen Penis albert. Oder ganz laid back in „Take It Easy“. .Damit hatte er seinen Durchbruch, obwohl der Song für die Eagles war. Für die Kinks schrieb er Waterloo Sunset, das wusste ich gar nicht. Ich habe leider Jackson Browne nie live gesehen. Vielleicht klappt das ja noch, er tourt noch immer.

Meine Songliste ist lang, sie ist seit über 40 Jahren gewebt:

These Days

The Pretender

Too late for the Sky

Here come the tears again

I am alive

Missing Person

Song for Barcelona(oder überhaupt das ganze Album, das er in Barcelona mit dem wunderbaren David Lindley gemacht hat)

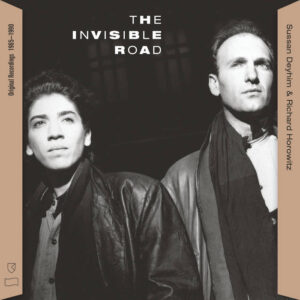

“The Invisible Road“

The Invisible Road: Original Recordings, 1985–1990 compiles an unheard, previously unreleased body of recordings by Sussan Deyhim and Richard Horowitz, dissidents from diametric backgrounds who met during the heady days of Downtown New York in the 1980s. This collection reveals the creative and life partners’ radical shared vision of avant-garde pop in all of its boundary pushing freedom, combining Deyhim’s singular approach to vocalization, Horowitz’s invention of new musical languages, and touchstones of traditional music from around the world, creating a new music that ultimately retains a voice entirely its own.

Yoshimi 2025, etc.

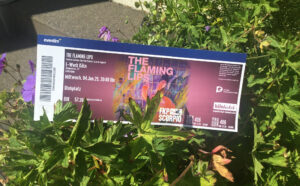

“Do You Realize“. Es ist so spannend, Olafs „Musikstories“ zu folgen. Schön, dass man eher selten das Zeitliche segnet, wenn man das eigene Leben in Rastern und Klängen vorüberziehen lässt. Da macht der Flaming Lips-Song schon Sinn. Sollte ich mal das Spiel mit den 5 Jahres-Sprüngen spielen, wäre mein fünftes Jahr ein gefundenes Fressen für jede Lebensstilanalyse. Aus irgendwelchen Gründen war ich nicht im Kindergarten, sass stets allein daheim auf einem roten Kissen, und hörte Radio. Wunderbar. By the way, es gibt noch ein paar Karten für das E-Werk in Köln, für den 4. Juli 2025, für das Flaming Lips Konzert!

on deep flow rotation in my electric cave this week: Flaming Lips: Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots (vinyl) / Joni Mitchell: Hejira (cd / remaster by Bernie Grundman) / Joni Mitchell: For The Roses (blu ray / newly released quad version) / Burning Spear: Garvey‘s Ghost (vinyl, and one of my ten most beloved dub albums ever) / Steve Kuhn: Ecstasy (vinyl, and for me his best album ever) / Brian Eno: Music For Films (1978, vinyl) /// quote of the week: „ One interviewer was astonished that Brian Eno had not influenced Gary Newman. “Everybody told me I’d like Eno, but I never used to like Roxy Music so I never listened to him. So I listened to Eno, and bought, I think, Before and After Science and didn’t like it much. And then I got Music for Films and thought that was brilliant.” We see, every music story is quite idiosyncratic, Olaf!

– 25 –

25 – Blumfeld – Old Nobody

Fast wird mir schwindelig, wenn ich an meine Jahre Anfang bis Mitte 20 denke. Auszug von zu Hause. 5 Umzüge: nach Potsdam, dann noch zweimal innerhalb Potsdams, nach Potsdam, New York im Nordosten der USA – ein Auslandsjahr an der Partneruniversität – mit Mitte 20 schließlich nach Berlin. WG Leben. Ich studiere Anglistik/Amerikanistik und Geschichte. Ich lerne meine jetzige Frau kennen. Ich werde Vater.

Klar, jede Menge Musik. Elektronische Musik kommt in mein Leben. Reggae, Dub. Trip Hop. Stundenlanges Tanzen in Berliner Clubs. Berlin ist in den 90er Jahren ein toller, für mich magischer Ort, viele Nischen, viele Freiräume. Durchfeierte Nächte. Und alles ist sehr günstig.

An meinem 25. Geburtstag, meine Freundin ist schwanger, feiern wir eine große WG-Party. Viele Freunde kommen, auch H und C, die damals bei der Musikzeitschrift Intro arbeiten. Sie bringen mir eine gebrannte CD mit, darauf das neue Album von Blumfeld, das erst in 6 Wochen erscheinen wird. Old Nobody.

Blumfeld hatten 1992 und 1994 jeweils ein Album veröffentlich, Ich-Maschine und L’etat Et Moi. Gitarren, Bass und Schlagzeug, eine flirrende Musik, mit seltsam atemlosen, vom Hip Hop beeinflussten, eher gesprochenen als gesungenen Texten, Geflechten aus Zitaten, Alltagssprache, Poesie und Diskurs, inhaltlich zwischen Gesellschaftsanalyse und Liebesliedern. Chiffernschriften, die sich in meine Gedanken einnisten.

Und nun also diese CD. Ich packe die zur Seite, mixe Cocktails, wir feiern bis zum Morgengrauen, überall in der Wohnung schlafen Menschen. Dann zum Frühstück lege ich sie in den Ghettoblaster in der Küche. Das erste Stück ist ein langes Gedicht, spoken words, wird schnell übersprungen.

What is this shit? Statt verzerrten Gitarren eine Drum Machine, Keyboard Flächen, sanfte, verträumte Gitarrenklänge. „In mir 1000 Tränen Tief/ Erklingt ein altes Lied/Es könnte viel bedeuten“. Eindeutige Texte, der Sänger Jochen Distelmeyer singt davon, in den Alltag zu wollen, stets dem Leben zugewandt zu sein, darüber sich gegenseitig „tief, ganz tief“ in die Augen zu sehen, „Küss mich dann/Wie zum ersten Mal“, „Da steht ein Pferd auf dem Flur.“ Und genau: er singt, ich mochte es doch immer so gerne, wenn er spricht. Und: es gibt im zweiten Song einen Kinderchor.

Der zweite Song klingt wie eine weichgespülte Blumfeld Coverversion, der nächste ist wieder schrecklich melodisch, im dritten läuft ein Disco Beat im Hintergrund. Was bitte ist hier los, was soll das?

Wir coolen Menschen Mitte 20 stehen verkatert in der Küche und sind ratlos, warum unsere Helden nicht mehr cool sind. Sondern: Gefühlvoll, weich, poppig. Und dann machen wir das Album wieder an. Und wieder. Und wieder. Und es läuft immer noch. In fünf Wochen gehe ich – doppelt so alt wie 1998 – zum Solo Konzert von Jochen Distelmeyer. Ick freu mir drauf.

– 20 –

20 A Tribe Called Quest – Midnight Marauders

Als kleiner Nachtrag: Zwischen 10 – 15 bin ich ein eher zurückhaltender, introvertierter (vor-) pubertärer Jugendlicher. Jeans, Strickpulli, Turnschuhe. Im Gymnasium an guten Tagen ein mittelmäßiger Schüler, „blaue Briefe“ flattern mehr als einmal ins Haus. Ich lese viel, Krimis von Edgar Wallace oder Agatha Christie, was halt so zu Hause rumsteht. Recht früh lese ich (wohl in der 8. Klasse) „Der Fänger im Roggen“ und „Die neuen Leiden des jungen W.“ und bin beeindruckt von der Unangepasstheit der Hauptfiguren – und deren Ablehnung der Gesellschaft.

Und mit 16 ändert sich einiges. Das Feiern tritt in mein Leben. Parties in Gemeindezentren und im Haus der Jugend. Manchmal auch Discos (ich darf bis 22:00 draußen sein). Alkohol. Schüchterne Schwärmereien. Und auf einmal jede Menge neue Menschen.

Der Soundtrack dazu ist vielfältig. F bringt eine Kassette mit – wahrscheinlich sind wir gerade 16 geworden, meine Eltern sind nicht zu Hause, sturmfrei. „Indie Mix“ ist der Titel, darauf sind die Pixies, They Might Be Giants, Hüsker Dü, Dinosaur Jr, Phillip Boa, Snuff, Nomeansno, vielleicht auch schon Yo La Tengo. Außerdem hat er sich schon eine Schallplatte mit dieser neuen Musik gekauft: „In God We Trust, Inc“ von den Dead Kennedys. Die Lieder sind – mit einer Ausnahme – unter 2 Minuten lang, alles ist sehr laut, sehr verzerrt, sehr schnell, sehr super. Nachdem wir erst das Tape und dann die LP gehört haben, sieht meine musikalische Welt sieht anders aus.

Und irgendwie kommt in der Zeit, vielleicht etwas später, Hip Hop in mein Leben. Sicher auch durch ein Mix Tape (von denen ich auch selber unzählige aufnehme und verschenke, als ich mein Tape Deck zur Reparatur bringen will, werde ich gefragt ob es im Profigebrauch gewesen sei). Sicher vor allem durch Artikel in der Zeitschrift Spex, die schnell den Musik Express ablöst und die ich bis sie schließlich 2018 eingestellt wird immer wieder lese.

Als ich 19 war habe ich aber den Blues und zwar so richtig. Meine Freundin hat Schluss gemacht, kurz vor der mündlichen Abi-Prüfung. Das zieht mir tatsächlich den Boden unter den Füßen weg, ich bin für ein halbes Jahr zu kaum etwas zu gebrauchen.

Gleichzeitig beginnt mein Zivildienst. Ich betreue eine Studentin, Mitte 20, die im Rollstuhl sitzt. Ihr Freund lebt in Trier, dorthin begleite ich sie immer wieder. Und dort, in einem kleinen Eckladen, stehen im November 1993 auf einmal zwei CDs, auf die ich schon sehr lange warte: „Doggy Style“ von Snoop Doggy Dog und „Midnight Marauders“ von A Tribe Called Quest.

Sehr lange Vorrede, aber das zweite Album geht es mir. Diese unglaublich positive und lebensbejahende Musik holt mich ins Leben zurück. Die Welt ist auf einmal nicht mehr schwarz-weiß, sondern farbig. Der Einfallsreichtum der Musik, die Detailverliebtheit, der rote Faden, der durch eine Art Moderatorin gesponnen wird, die Texte – all das macht einen großen Eindruck auf mich, bereitet mir Freude. Aber das Beste sind die beiden Rapper: das Zusammenspiel von Mastermind Q-Tip mit dem anti-hesitator, funky diabetic Phife Dawg ist einzigartig. Und all das macht mir mit 50 immer noch viel Spaß und gute Laune. Musik hat mir aber noch nie so viel Trost gespendet wie im November 1993.

(Ich habe lange überlegt, ob ich nicht doch das Album „Illmatic“ des Rappers Nas nehme, über das ich irgendwann noch einmal schreibe. Ein Gitarrenalbum hat sich komischerweise nicht so aufgedrängt, kommt aber dann zum Eintrag 25.)

“Our Time“ – a jazz hour at the Deutschlandfunk

Here we go. Thanks to some supportive agents in the background, my „JazzFacts“ of September 6, 9.05 p.m. have now finally been shaped. Always possible that there‘ll be another last minute change, but this following sequence is nearly carved in stone. Two albums from Pyroclastic, two from ECM, one from Red Hook and WeJazz – and a „Souffle Continu“ reissue of Byard‘s Lancaster‘s works on Palm Records (1973-74) promise different kinds of thrill and blue.

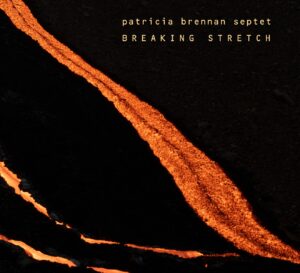

Next year, I will do (at least that’s the plan) four „Klanghorizonte“ hours in a row, in March, May, July and September, and a one hour portrait of an artist still to be chosen. The end of my radio years. So, hurry up, Steve Tibbetts – what started in October 1989 with a „Studiozeit“ on the guitarist from Minneapolis, could be the best way to let the curtain fall. In November 2025. Now, as I said before, here we go, starting with a composition from Patricia Brennan‘s forthcoming album, „Palo de Oros“.

Paul Lyytinen: Lehto / Korpi (WeJazz)

feature one: Florian Weber: Imaginary Cycle (Niklas Wandt)

Frisell / Cyrille / Downes: Breaking The Shell (Red Hook)

Fresh from the archive: Byard Lancaster on Palm Records (1973-74)

Patricia Brennan Septet: Breaking Stretch (Pyroclastic)

feature two: Miles Okazaki: Miniature America (Karl Lippegaus)

Trygve Seim / Frode Haltli: Our Time (ECM)„The Forests Of Your Mind“ – an interview with Paul Newland aka Clevelode

„Round, like a circle in a spiral / Like a wheel within a wheel / Never ending or beginning / On an ever-spinning reel…“ Well, that‘s another song, but leading on the right track. “Muntjac“ by Clevelode took me by surprise. In many ways. At first it may be easy to speak about a wonderful balance of song and ambient worlds. But there is so much more revealed in this epic, minimal, grandiose, ascetic, captivating, „less-is more“ cycle of songs and atmospheres than any clever amalgam of styles may suggest.

I wanted to send my questions to multi-instrumentalist, singer and composer Paul Newland quite soon, after first listening, but then they seemed like take from the standard book and doing no justice to the album. I returned to this work, again and again, and there is no other way than to do it in the old-fashioned way, from start to end (being aware of the fact you might get lost on the way).

As time went by, I felt myself walking through Epping Forest, or, better said, through those green power spots of younger and older days on the margins of Dortmund. Though there are references here and there, „Muntjac“ is a completely idiosyncratic work of art, far away from any rip-off from other classics of this and that genre. Which genre anyway, you may ask after another deep walk & listen. Though the geographical coordinates seem crystal clear, this journey is „Where-am-i-music“ in the best sense. So many ways inside the shades of blue, the trees of green… but the easy access doesn‘t take away any of its mysteries!

Michael: The second piece of the album, ‘High Beech’, is a fantasy and reflection at the same time: the importance of that forest as life‘s company, and a time travel experience from a distant past to future times. A figure appearing here, like a ghost, is the poet John Clare. Apart from being a quintessentially romantic poet, can you tell something about his role here, in a kind of key track of the whole album?

Paul: It’s nice that you think ‘High Beech’ is a key track, Michael. I agree. And I think your reading of the song is spot on.

Clare’s link to the area was very much in my mind when I thought about making an album about Epping Forest. But the song ‘High Beech’ was written very quickly, with barely any editing of the lyrics. I kind of came out of nowhere. I didn’t set out thinking about Clare. But he appeared as I wrote. It was as if he was lurking in my subconscious. Perhaps I was also projecting myself – as a lone ‘poet’ wanderer in the forest – onto the figure of Clare – although that sounds rather pretentious!

My interest in psychogeography and stories of east London have been profoundly influenced by the writer Iain Sinclair, whose book on Clare, Edge of the Orison, was probably lurking in my mind somewhere too.

I was aware of the asylum in High Beech as a kid (my grandparents lived near there), even though I only learnt about Clare and his time up there as an adult. In one of my favourite Clare poems “The Gipsy’s Camp” he writes: “My rambles led me to a gipsy’s camp, / Where the real effigy of midnight hags, / With tawny smoked flesh and tatter’d rags, / Uncouth-brimm’d hat, and weather-beaten cloak, / ‘Neath the wild shelter of a knotty oak, / Along the greensward uniformly pricks / Her pliant bending hazel’s arching sticks.” I think some of the lines in ‘High Beech’ probably owe a debt to these lines – the reference to the gypsy train, for example.

The song ‘High Beech’ is also influenced by the late-Victorian novel After London; Or Wild England by Richard Jeffries. I wanted to use the lofty forest landscape to imagine a future in which High Beech actually becomes a beach, after Essex and London are flooded. So there is an almost post-human ecological slant to the song – and to the album – too. The forest as portal to the past, present and future.

On the title track, ‘Muntjac’, the transparency and the airy jazz bass bring to mind – in moments – a kind of ECM-‘space’, soundwise. Do you have a close relationship to some more or less ancient ECM albums, maybe even some with a direct link to nature like Jan Garbarek‘s „Dis“?

Yes, I’m a fan of Garbarek, and of Dis in particular. I’m a fan of a lot of ECM music. Keith Jarrett. Ralph Towner. Chick Corea. Terge Rypdal. Eberhard Weber. Weber’s The Colours of Chloë is a big favourite of mine – I love the picturesque, romantic, minimalistic and harmonically interesting nature of the music.

One of the things about ECM that I like is how a lot of the music they put out refuses to acknowledge boundaries between genres. I think ECM’s motto is „the most beautiful sound next to silence“. My music is often quiet! They put out beautiful recordings. Such care and attention to detail.

I also write about film, and I’m aware that ECM has a special relationship with film, and has released some interesting soundtracks, such as Histoire(s) du cinémaby Jean-Luc Godard.

It is easy to speak about a melange of song structures and ambient music. But there’s a lot going on in these long instrumental pieces. For instance, the first track, ‘Loughton Camp’: looking back on it, can you feel some more or less hidden, unconscious influences that may have crept into the making that, interestingly enough, begins with very high notes that normally signal danger…

I think I’m a songwriter first and foremost. Recently I’ve been trying to think about more experimental ways to write. Tim Noble was a huge influence on me when we worked together in the Lowland Hundred. He really encouraged me to think and work more experimentally. To take risks.

Working largely on my own as Clevelode, I think I’m being a bit more experimental than I have perhaps been before, as a writer and as a musician/composer/arranger. Although songwriting requires structure, harmony, melody, rhythm, and tends to obey certain rules, I’m trying to embrace improvisation, chance, and even mistakes. This approach informs the songs, but also the instrumentals on the album.

I’m also getting much better at editing. I enjoy editing as a kind of meditative, unconscious pursuit. I try not to think about it too rationally. I allow myself to work on feel, on hunches. I try to trust unconscious decision making. No doubt this is where some my influences come through. Probably a huge influence on me has been the work Miles Davis did with Teo Macero. Also, of course, Mark Hollis’s work with Tim Friese-Greene on the late Talk Talk records has had a profound effect on me.

The long instrumental pieces have a unique sound field. Nothing here seems easily comparable. And in opposition to a strictly minimal approach, there‘s a lot happening, for instance, during the last two tracks: i remember, at one moment, out of nowhere, the strumming of an acoustic guitar. Your are not simply entranced by purely repetitive elements, you have to be ready for something unexpected at any time … can you shed some light into the ’tone poems’ or ‘tone stories’ of these last two tracks. Again, there may be some subtle influences…

The long instrumental pieces on the album are the result of improvisation. I’ve embraced the use of analogue synths in my work for the first time on ‘Muntjac’. I use a Prophet 5, a Moog Matriarch, and a Behringer Odyssey. These are incredible instruments. Part of the fun of this has been the ‘not-knowing-what-you-are-doing’ aspectof it. Just playing, mucking about with filters. Learning an instrument on the fly!

I like music to be unpredictable. I like to use different colours and textures, to create and maintain interest. The acoustic guitar in ‘Ambresbury Banks’ was a result of listening to what I had done with piano and synth and thinking ‘this needs another colour’, or another ‘voice’. I just reached for the guitar and improvised, first take. Sometimes on long instrumental pieces it is good to have a few sonic landmarks – interesting things the listener can navigate by.

While the opening and ending passages of the album evoke the sense of Epping Forest, of nature, the more central pieces, often much shorter, do the storytelling… ‘Grimston‘s Oak’ reminded me at one moment of a Damon Albarn song on his fantastic song cycle ‘Everyday Robots“, the phrasing of your singing probably… strange coincidence? By the way, the sequence of the album is perfect.

I admire Damon Albarn. An interesting artist. Like me, he is from Essex. Perhaps there is a link in terms of how we sing, phrase and enunciate words, as you say! He wrote a song called ‘Hollow Ponds’ (on Everyday Robots) which is about a place I lived very close to in Leytonstone for a while. I think Albarn lived in Leytonstone for a bit too. On the edge of Epping Forest. But I don’t listen to his music much, if I’m honest. Maybe ‘Hollow Ponds’ was lurking somewhere in my unconscious, though.

I’m very happy you think the sequencing of the album works well. It’s so important to get the sequencing right! This took a lot of time! Having two long instrumentals bookending the album was an early idea. I think of them as portals into the world of the album. Both ‘Loughton Camp’ and ‘Ambresbury Banks’ are iron age forts in the forest.

I know you love that long Miles Davis piece ‘He Loved Him Madly’ from Miles Davis… an influence, too, for Brian Eno making On Land… the trumpet as the figure in a ‘landscape“… similar to your history with long walks and biking through Epping Forrest: do you love to return to certain musics from time to time, like the Miles Davis composition, or are such pieces so deeply engraved in your memory, that they more function on a subconscious level in your present life?

Miles Davis’s work from the late 1960s through the mid 1970s continues to have a huge influence, yes. I certainly return to his music as much – if not more – than anyone else’s. For me, ‘He Loved Him Madly’ is just magic. This is Davis’s threnody for Duke Ellington. I love the organ drone. I love the tasteful and interesting electric guitar work by Reggie Lucas and Dominique Gaumont. Al Foster’s snare and bass drum work. I love the way the piece slowly and patiently creates a sense of space through harmony and rhythm. You can hear this music being ‘built’. It’s architectural. Over 30 minutes! I love Get Up With It, but also the long tracks on Big Fun and Circle in the Round – particularly the 18-minute version of David Crosby’s ‘Guinevere’, and the 26-minute title track.

Recently I’ve been listening to a lot of music by Wayne Shorter (particularly Schizophrenia and Odyssey of Iska), Herbie Hancock (particularly Crossings, Sextant, Mwandishi, Thrust), Harold Budd, Charles Mingus, Bill Evans, Alice Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, David Axelrod. Also Eno, who you mention, and Labradford, Mogwai, Boards of Canada. I imagine influences have crept through, particularly on the instrumentals on ‘Muntjac’.

In our young days we were often listening to albums for weeks, they blocked our record players. Did you recently have had a similar obsession to listen to an album again and again, or have your listening habits changed?

Yes – I’ve been collecting vinyl again over the last few years. Spending too much money!!! But there are so many gorgeous pressings of jazz albums being released. I can’t resist them. The albums I buy I tend to play over and over again on my inherited 1970s hi-fi. It’s like a fine dining experience. I like to really listen to music, to really savour it and digest it, I like to make it an almost ceremonial banquet-like experience!

Stuff I’ve Been Listening To

I’ve been listening to the new Giovanni Guidi album, A New Day a lot, and had written a detailed review to post here last week. Unfortunately, due to a freak accident, I lost the file just as I was about to post it. While not inclined to write another detailed review, I will just say here that it is an exquisite album which starts right out of the gate with a couple of dreamy rubato tunes in a row, setting the atmosphere for this largely introspective, ruminative recording. This album features some really nice writing on Guido’s part, with the exception of a free group improvisation and a distinctly abstract version of the standard, My Funny Valentine.

Guidi always sounds great, and this outing is no exception. There are a few pianists out there as consistent as Giovanni Guidi. The same could be said about bassist Thomas Morgan, who seems to be appearing as a sidemen these days on a lot of records I like. The real surprise for me here was tenor sax master James Brandon Lewis, who I had not heard of before this record. Lewis is an unerring melodicist, and doesn’t seem to play a note he hasn’t completely internalized. Last but not least, drummer Joao Lobo keeps it all moving, with his subtle colors and when needed, solid groove. The album ends with the marvelous piece, Wonderland, which starts out with a rubato melody played in unison on piano with Lewis on sax. It’s a wistful, yet optimistic tune, vaguely reminiscent of some of Jarrett’s writing for the European Quartet. Eventually it goes into 3/4 time and a simple yet effective modulating Lydian progression becomes a vehicle for joyful improvisation which builds and then takes us back home to the lovely rubato intro melody.

I am also revisiting a couple classic PMG albums I recently bought in SHM SACD format. The first (aka White Album,) album has always been a favorite, and it sounds only marginally better in SACD format. Of all the new Japanese PMG SHM SACD reissues, I would say OffRamp sounds the best of this lot, but then, the original album already sounded pretty darn good. I already had the earlier SACD issue of Travels, which definitely benefitted markedly from the transfer and is still a favorite, especially in this format. Worth tracking down that one.

Incidentally, none of these SACD reissues are remasters, and honestly, they are not a huge upgrade in terms of SQ. I have always thought that PMG was given short shrift sound-wise on these early group albums, and I’ve never understood why they weren’t remastered, or better yet, remixed (doubt either will ever happen.) The same goes for Bright Size Life, which I also bought as a new SHM SACD. This one fared the least well of all these newish SHM SACD releases. Not that great recording in the first place, and there’s just not a whole lot of definition to recapture at a higher sample/bit rate, because it just wasn’t there in the first place.

Speaking of Pat Metheny, I’ve been listening quite a bit to the new solo baritone guitar recording, MoonDial. I’ve really been digging it. It has a number of new Metheny compositions, as well as a lovingly rendered version of Here, There and Everywhere, which modulates a few of times in a very subtle, tasty way. Metheny also manages to breathe new life into the Chick Corea composition, You’re Everything off of the iconic Return to Forever album, Light as a Feather, taking it all the way from the original uptempo samba down to an introverted ballad. And it really benefits from the reinvention. Metheny finds all kinds of sweet harmonic nooks and crannies to caress in this little gem. Listening to it at this slow tempo, one realizes just how beautiful this tune really is. He also puts together a really nice medley of Everything Happens to Me and the Bernstein (West Side Story) composition, Someday. At this stage of his career, Pat Metheny can take a tune like the much covered Londonderry air, a.k.a. Danny boy, and remake it into completely fresh. With its ingenuous chord substitutions, this reharmonization exceeds most versions I’ve heard in terms of harmonic invention. Metheny also explores two other standard ballads, My Love and I and Angel Eyes, breathing new life and substance into both of these chestnuts. The engaging, highly Metheny-esque title track bookends the album, giving a full reading at the beginning and then returning as a short reprise at the end of the album.

Perhaps one of the best things about this album is the sumptuous sound of the guitar itself. Linda Manzer, who has been Pat Metheny’s luthier for decades, has really outdone herself here. As great as the baritone guitar sounded on the first solo album, One Quiet Night, a couple years ago Metheny asked her to build him a new guitar for the DreamBox tour, one which was specifically designed for nylon strings. Apparently it was quite difficult to locate a set of nylon strings that would fit a baritone guitar, and Manzer had to scour the globe in order to procure a set. All I can say is, the search was worth it; The guitar on this album is the perfectly balanced electro/acoustic blend. It has the warmth, detail and intimacy of an acoustic nylon, but also possesses the deep bottom and color of an electric. It fills the entire room, and one sometimes gets the sense Metheny is working with a portable orchestra in a guitar case.

Metheny doesn’t feel the need to show off on this record, instead choosing understatement and subtle fretwork which underscores the beauty of the instrument and brings out the lyricism of the chosen originals and covers. This is a very laid-back album which suits my mood these days, when I find myself seeking solace in quiet down tempo music. And this gem fits the bill perfectly. It’s comfort food for the soul, but not without its nutritional benefits.

Tatami

Ein unerwartet intensiver Kinobesuch: „Tatami“ von Zar Amir und Guy Nattiv. Fantastisch guter Film, klarer 5-Sterne-Film; ich wüsste gesagt nichts, was ich daran auszusetzen fände. Perfekt erzählt, in sagenhaft tollen Bildern (Kamera: Todd Martin) und von exzellenter Regie mit grandiosen Schauspielerinnen inszeniert. Auch in der epd film gibt es die Höchstwertung – „ein politischer Thriller um strukturelle Unterdrückung und individuelle Freiheit“. Die Kampfszenen wirken so eindringlich wie einst jene in „Raging Bull“.

Iranische Filme, die bei uns im Kino oder auf Festivals laufen, sind eigentlich zuverlässig sehenswert, oft hervorragend, seit ich Kinogänger bin, und so wollte ich eigentlich schon schreiben, „Tatami“ dürfte ein sicherer Kandidat für den „Oscar für den besten internationalen Film“ sein – und dann sah ich, dass es eine US-Produktion ist. Ob die so mutig sind, so einen kleinen Film mit relativ unbekannten Schauspielerinnen für den „nationalen“ Oscar zu nominieren…? Kann ich mir kaum vorstellen, auch wenn in den letzten Jahren ja immer mal wieder auch Filme mit nicht-englischsprachigen Dialogen für die großen Preise nominiert worden sind. Aber vor allem hat Guy Nattiv derzeit ja noch einen anderen, weitaus größer vermarkteten Film mit Helen Mirren als „Golda“ im Oscar-Rennen, für den die Hauptdarstellerin als Nominierte quasi gesetzt ist. Den hab ich allerdings nicht angeschaut: mir sah das zu sehr nach musealem Austattungs-Geschichtsstundenkino aus. Sicher inhaltlich und schauspielerisch interessant, ästhetisch oder künstlerisch allerdings eher nicht so relevant.

„Tatami“ sieht man an, dass die Leute hinter der Kamera Ahnung vom emotional ausgelegten großen Kino haben, und der Film ist auch klar als Genrestoff als hochspannender Thriller im Sportmilieu erzählt; es gibt auch einige Kamerakniffe, die verraten, dass das Ganze nicht super-billig und super-indie gewesen sein kann, doch die Geschichte wird immer sehr präzise, sehr klar und ganz nah an den Charakteren erzählt. Für mich ein wichtiger Faktor. Die Komponistin der eindrucksvollen, die Spannung hervorragend zuspitzenden Filmmusik, Dascha Dauenhauer, ist übrigens Deutsche (wenn auch in Moskau geboren) und hat nach ihrem Studium in Berlin und Potsdam in kürzester Zeit eine internationale Karriere hingelegt. Vor drei oder vier Jahren hat sie noch Musik für kleine deutsche Filme geschrieben, war allerdings in einem Jahr gleich für drei Deutsche Filmpreise nominiert, bevor sie, noch als Filmmusik-Studentin in Potsdam, für mehrere, auch international wahrgenommene große Serien die Musik schrieb. Aufgefallen ist sie mir wohl erstmals in der ebenfalls außerordentlich gelungenen und bewegenden Miniserie „Deutsches Haus“, die meisterlich inszeniert war.

Hier ein aktueller kleiner Text über aktuelle iranische Filme: „Wenn Filme Widerstand sind„. In der Frankfurter Allgemeine gab’s letztens auch ein überaus lesenswertes Interview mit den beiden Regieführenden:

Frau Amir, identifizieren Sie sich als Künstlerin mit dem Schicksal der Sportlerin?

Zar Amir: Unbedingt. Die Geschichte, die der Judoka zustößt, ist mir fast genau so zugestoßen, auch Kollegen und Regisseuren. In einem Land wie in Iran verstehen wir die Athleten sehr, sehr gut. Ich verstehe nur nichts von Judo.

Warum war das Milieu dieses Sports so relevant für die Story?

Guy Nattiv: Judo ist ein Sport mit Würde, Ehre und Regeln. Die Wichtigste ist, den Gegner zu respektieren. Wenn man ihn nicht ehrt, ehrt man den Sport nicht. Die iranische und die israelische Judoka, die eventuell gegeneinander antreten müssen, ehren beide diesen Sport und können das Politikgeschachere ihrer Regierungen nicht respektieren.

(Ein weiteres Interview mit Guy Nattiv hält epd film bereit.)

– 15 –

15 Talk Talk – Spirit Of Eden

Zwischen 10 – 15 erweitert sich mein Radius. Kommt vorher die Musik entweder durch meine Eltern, meine große Schwester oder das Radio in mein Kinderzimmer (bzw. durch den Fernseher ins Wohnzimmer), werden die Tore zur Welt immer größer, zahlreicher, die Möglichkeiten Musik zu hören auch. Aus dem Kinderzimmer ist ein größeres Jugendzimmer geworden, ein Auslandsaufenthalt meiner Schwester löst innerhalb des Hauses einen Raumtausch aus. Und der Radiorekorder wird durch eine gebrauchte Kompaktanlage von Schneider abgelöst.

In der mittelgroßen niedersächsischen Stadt gibt es allein in der Fußgängerzone 5 Läden (mit Namen wie Record Corner, Brinkmann, Montanus Aktuell oder Radio Deutsch), die mindestens eine große Abteilung für Schallplatten, Kassetten und die neuen, funkelnden CDs haben.

Dann gibt es da noch eine wunderbare Institution: die Musikbibliothek. Die ist in einem spätmittelalterlichen Gebäude mitten in der Stadt ansässig und hat zwei Besonderheiten. Zum einen den großen Saal (die Decken müssen mindestens 4 m hoch sein) mit Hörplätzen. Ich kann also im Katalog nachschauen, was ich hören will, der Bibliothekar (ein sehr freundlicher Mensch) sucht mir den Tonträger aus dem Archiv und macht ihn an. Ich bin an meinen zugewiesenen Platz, setze die Kopfhörer auf und tauche in die Musik ein. Etwas später gibt es dann dort die Möglichkeit, sich CDs auszuleihen. Es ist natürlich streng verboten, die dann auf eine Leerkassette aufzunehmen, aber daran hat sich auch damals niemand gehalten. Wobei ich mir einbilde, dass meine Eltern ziemlich streng gucken.

Mit 12 oder so beginne ich dann außerdem regelmäßig „Musik Express / Sounds“ zu lesen. Im ersten gekauften Heft ist „Gracelands“ von Paul Simon die Platte des Monats, die dann auch gleich gekauft wird – immer noch ein schönes Album mit einigen tollen Songs. Auch ansonsten ist mein Musikgeschmack nicht sonderlich ausgefallen: U2, Supertramp, Queen, Dire Straits, The Housemartins, David Bowie, Die Toten Hosen, Rolling Stones, Marius Müller-Westernhagen, The Cure, immer noch The Beatles und etwas später kommen dann The Doors oder Pink Floyd dazu. Schlussendlich spiele ich zwei, drei Jahre E-Bass und komme in Kontakt zu der Jazz Musik von Weather Report oder Chick Corea.

Eines Tages lese ich im „Musik Express / Sounds“ die Besprechung einer Platte des Monats: Spirit Of Eden von Talk Talk. Der Rezensent ist schwer begeistert, die Beschreibung der Musik klingt interessant, ungewöhnlich, das Cover sieht wunderschön aus. Und als ich am Freitag derselben Woche meine Runde in die Musikbibliothek mache, hat der freundliche Bibliothekar gerade die neuen Erwerbungen einsortiert, darunter eben die neue Talk Talk, die ich mitnehme, genau so wie „The Whole Story“, eine Greatest Hits Compilation von Kate Bush.

Nach dem ersten Hören habe ich Kopfschmerzen, so etwas habe ich noch nie gehört. Was ist das für Musik – ist es überhaupt Musik? Die CD läuft das ganze Wochenende, meine Familie ist genervt (‚kannst Du nicht wenigstens mal etwas anderes anmachen?). Für mich ist die Musik wie ein Rätsel, das ich ergründen möchte. Ich nehme sie auch auf Kassette auf, „The Whole Story“ kommt auf die Rückseite. An dem Wochenende ist in der Tageszeitung ein Gemälde von Dalí in schwarz-weiß abgedruckt, das ich ausschneide und als Cover benutze.

Und ich kaufe mir „Sketches Of Spain“ von Miles Davis als meine erste eigene CD überhaupt. Im Musik Express stand, dass das ein Lieblingsalbum von Mark Hollis sei.

Insgesamt läuft in der Zeit „Spirit Of Eden“ sicher nicht so oft wie „Damenwahl“ von den Toten Hosen. Aber ich habe seither das Talk Talk Album sehr viel häufiger gehört, es hat mich musikalisch geprägt, hat Türen in unterschiedliche Richtungen geöffnet – Jazz, Avantgarde, Psychedelia, Blues – und mich die Schönheit von Klängen gelehrt.