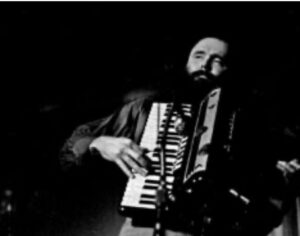

RIP Garth Hudson, the last man standing

RIP Garth Hudson, The last man standing. Garth was the secret weapon behind the Band’s sound. His organ and keyboard playing, not to mention his accordion, sax and arranging skills, coupled with his vast musical knowledge, elevated the band’s sound, and was the glue that held it all together, but of course it was ultimately the synergy between all its moving parts that resulted in that unmistakable and paradoxically loose knit but at the same time, tight groove they alone could conjure.2024 listening list

I don’t focus much on new music, nor do I prioritize listening to something based on its being newly released. That being said, here’s a random list of some of the stuff I’m listening to which happened to come out in 2024, in no particular order:

Planetarium – Ben Monder (a monster of a record – (3 CDs and stays coherent and focused all the way thru)

Touch of Time – Arve Henriksen, Harmen Fraanje – (quiet, meditative sound paintings)

Milton and Esperanza – Milton Nascimento and Esperanza Spalding -( joyous, affectionate and intimate music)

Moondial – Pat Metheny – (soothing, calm pieces played on a lovely sounding baritone guitar)

Y’ Y – Amaro Frietas – (earthy, impressionistic, Amazonian jungle sounds)

Little Big III – Aaron Parks – (Little Big’s third album might be their best so far – trippy “jam band” music with great writing.)

Balalake Sissoko and Derek Gripper – Balalake Sissoko and Derek Gripper (Kora master with classical guitarist who has beautifully brought Malian kora repertoire to the guitar)

Taking Turns – Jakob Bro – (lovely stuff, much of which is related to Black Pigeons.)

Celebration – Wayne Shorter (perhaps the best live last quartet album)

First Song – Soren Bebe Trio (another beautiful, understated album by the quiet Danish pianist.)The Sky Will Still Be Here Tomorrow – Charles Lloyd – (a gorgeous album by the master of subtlety.)

Out of Into – Motion I – Joel Ross, Gerald Clayton, Immanuel Wilkins, Matt Brewer and Kendrick Scott – (cutting edge burning state of the art jazz from the next generation of masters.)

I’ve been following Joel Ross’s career for a long time, as well as Gerald Clayton’s. I’ve seen both of them together and separately a number of times and in different contexts. They are both incredible bearers of the flag, steeped in the history and yet looking forwards, as are all their compatriots. Fearless, essential stuff.

A Spontaneous Discussion of Musical Hybrids

[I recently had a discussion on social media with an iconoclastic instrument inventor who had a lot of strong ideas about the state of today’s music and the industry itself. One thing he touched upon was the uselessness of categorization of musical styles. He didn’t like the term “World Music” because he felt every music on the planet was in a very real sense, “World Music.” How could I not agree? What follows is a short essay I wrote when he suggested that not enough cross-pollination is going on in today’s musical realms. He also asked what it might’ve been like if European composers had, for instance, incorporated Indonesian music in their orchestral works.]First of all, in my opinion, the term “World music” is a perfectly fine way to describe music from around the globe. I have no problem with it and it sure beats the term “ethnic”. In truth, I consider all of these categories as arbitrary, and are essentially meaningless, as for the most part they don’t convey any useful information, and are created by suits to describe music primarily so they can sell it. A lot of contemporary artists don’t fit neatly in a pigeon hole.

There’s a lot unpack in your comment, but I’ll just say this: cross cultural pollination is exactly what is happening today and it’s never been more vibrant.

And it goes back a long way:

In fact, European composers did exactly what you have suggested – incorporate gamelan music, and as early as the late 19th were influenced by it. Debussy is a good example: when he first heard a Javanese gamelan at the Paris World Fair in 1889, it totally flipped him out and it influenced his work, especially in pieces like Pagodes.

The first wave of the influences of different cultures always seems to start out as a passing, rather shallow toe dip into foreign waters, usually followed by a much deeper dive. For example, in the European dominated symphonic traditions, we later find composers like Colin McPhee, who lived in Bali for a number of years in a hut in the middle of a rice field, with an old upright piano, and wrote some magnificent music.

in the 50s Lou Harrison, who also studied Balinese and Korean music, composed music for both gamelan and western ensembles. He incorporated some of the Balinese techniques such as kotecan (interlocking parts,) into his chamber music compositions. Check out his wonderful Concerto for Violin, Piano and Small Orchestra. Find the CRI version conducted by Leopoldo Stokowski if you can. A contemporary of Harrison, Henry Cowell was another pioneer in bringing the music of Persia and Asia into Western music.

Also, Jody Diamond of Gamelan Sekar Jaya fame comes to mind. Along with Ingram Marshall, she became an important composer of new music for Gamelan. There is also a new generation of Balinese composers who have in turn been influenced by western composers. There are countless examples of this kind of thing. Indeed, today we live in a world where cross cultural pollination is no longer rare, but in fact, the norm. It’s literally everywhere, in pop, jazz, electronica, classical etc. In a way, this hybridization is the cornerstone of 21st century music. It’s a huge subject, and I’m only going to focus on jazz for the rest of this piece.

Jazz is an art form that started right out of the gate as a cultural hybrid, in this case primarily a blend of African music/rhythm and European harmony, and also soon incorporated popular music from the American songbook, which was sourced mostly from show tunes and films. Later, artists like Dizzy Gillespie became fascinated with Cuban music, and thus began a longstanding tradition of cross pollination between two cultures that is still vibrant today.

The same thing holds true of American jazz musicians like Stan Getz and Charlie Byrd, who started hanging out and playing with Brazilian musicians in the “first wave” in the 60s, but once again, it quickly became a two way street, morphing into an ongoing feedback loop where at a certain point it became difficult to parse who was influencing whom.

Artists like John Coltrane and Miles Davis experimented with incorporating Indian music into their music in the 60s and early 70s. After all, jazz being an improvisational tradition, it seemed only natural for western jazz artists to start playing with Indian musicians. Later, artists such as John McLaughlin (who seriously studied the Raga and Konecal systems) and Indian tabla master Zakir Hussein, who helped bridge the cultural divide from the Eastern side, came together to form Shakti, a true east/west collaboration that remains active today. Of course there were earlier experiments. The much earlier collaboration between Ravi Shankar and Yehudi Menuhin comes to mind.

Another Miles Davis alumni and one of the founding members of Weather Report, Vienna born Joe Zawinul always brought together musicians from all over the world into his bands, which allowed each artist to bring his or her individual cultural voice to the table. I have always thought of Zawinul as a visionary, not just because of his wonderful musical contributions, but because of his utopian vision of a world in which each culture remains unique and distinct, yet comes together to create a harmonious whole.

And any discussion of hybrid music which blends the influences of different cultures would be incomplete without mentioning Paris born Vietnamese virtuoso guitarist/composer Nguyen Le, yet another cutting edge musician who has created a kind of “world jazz” that’s entirely unique, collaborating with African, Moroccan, Vietnamese, Sardinian and American artists (just to name a few,) to create his own unique hybrid.

Cuban piano/keyboardist Omar Sosa, has become an ambassador of unique collaborations with artists from other cultures. Pictured above is his SUBA trio with African kora master, Seckou Keita and Venezuelan percussionist maestro, Gustavo Ovalles. Sosa exemplifies the healthy exploration of searching for and finding common ground between cultures.

Tigran Hayasman is another interesting example. As a young boy living in Armenia, he started off as a classical pianist but soon became fascinated with jazz. He was a prodigy, and while still in his teens, won the Thelonius Monk competition. But Tigran quickly outgrew the constraints of the jazz label and started making music which is impossible to categorize. He loved the complex time signatures of his native country and soon incorporated them into his own compositions, combining traditional folk melodies with heavy metal, prog rock, electronica, hip hop, pop and classical music. The result is hard to describe, and while I realize it is an acquired taste for some, I find it challenging, often quite beautiful and staggeringly original.

Last, but hardly least, Oregon needs to be mentioned. To me they exemplify the essence of intelligent, passionate musical cross pollination. They effortlessly blended western contemporary classical, jazz, free improvisation, world music of all sorts, and in the early days at least, East Indian influences in particular, to create an emblematic hybrid that has stood the test of time. Indeed as the decades have rolled by, their importance has only grown in stature.

In this world of ours, which has gotten so much smaller thru technology, this kind of thriving collaborative community is only natural and ongoing in virtually all genres and subgenres.

The subject of cultural appropriation sometimes comes up in discussions like these. What I have learned regarding whether it is appropriate to borrowing from other cultures has a lot to do with the culture one is borrowing from, and the attitude of the person doing the borrowing. For instance, in Bali, my sense has always been that Balinese musicians are very open, and generally love collaborating with people from other cultures. They not only welcome it, they have a long tradition of embracing it. My own teacher in Bali once proudly played me a cassette of himself playing drums with a gifted young Australian blues guitarist. The whole time it was playing my teacher was proudly beaming at me. The Balinese people have always been open to experimentation; I once attended a performance in Bali in which all the musicians were sitting down at synthesizers instead of traditional acoustic gamelan instruments.

On the other hand, my longtime music mentor, who is friends with a number of musical luminaries and considered to be one in certain circles, once told me a story about a famous artist who had borrowed an mbira part which he incorporated into a contemporary track. Apparently, when the African artist who had played the mbira part heard the finished track, he broke down in tears, because to him this was sacred music, and it was being desecrated by being used in what he perceived to be a secular context.

At one point, I was considering taking up the traditional African mbira myself, and the teacher I asked for lessons snubbed me because she felt that I was going to use it in my own music and that I didn’t show enough respect for the sacredness of the tradition in order for her to accept me as a student.

My take on cultural appropriation is that one should always ask one’s teachers and fellow musicians how they feel about incorporating their music into one’s own. That being said, my own experiences have shown me that for the most part, musicians from other parts of the world are flattered when an artist shows interest in their musical culture.

Thoughts on Listening

I am not a quick study when it comes to music. I often describe myself as an eternal student of the craft and spend time every day learning new concepts and getting them under my fingers. It usually takes a year or longer before a concept percolates into my playing.

How that applies to listening to music is that I am by and large not a rabid consumer of new music. When someone recommends an album to me by an artist I don’t know, it takes me a long time to discover what makes that album and the artist tick. If I decide I like it enough to really “take on” an album, that usually translates to hours of deep listening, sometimes study and even possibly a transcription of a tune or part of the solo. In short, I am anything but a passive listener.

This has its advantages and disadvantages. The obvious advantages are, by going deeper into a smaller number of new albums, I gain a deeper understanding of what’s really going on in the music, which greatly enhances my listening enjoyment. For me, listening is a very active thing, and it requires the attention of both my intellect and my emotions. Because after all, on a certain level, what is music, if not mathematics invested with human emotions? In my view, the best music is a balanced amalgam of the two.

The disadvantages are obvious: I don’t seem to have nearly the ability to absorb a large volume of new music as I once did; I honestly envy those who do. I have a friend who used to be the editor of and a contributing reviewer for a prominent audiophile magazine. We recently had a discussion on this very subject and here are his thoughts: “Yes, I’m one of those friends of yours who does NOT listen to a new and much-loved album over and over. I am very chary of overexposing myself to stuff I love and wearing out my appreciation of it. This has the odd result of my greatly loving many recordings without actually knowing them very well. I was sort of naturally bent this way anyway, in a sort of default asceticism, but then my work at (name of magazine) pretty much demanded it. I couldn’t linger. Had to keep listening to, or at least sampling, new disc after new disc after new disc.”

I have another friend who owns around 8000 CDs and thousands of downloads. He recently sent me a large volume memory stick filled with hundreds of his favorite things. He is one of the most eclectic music lovers I have ever met. In this “trove” as he likes to call it, is a hefty collection of classical (he was once a classical radio DJ,) jazz spanning many decades and sub genres, folk, world, esoteric pop and experimental recordings which don’t really neatly fit a category, all of which would take hundreds of hours to sample, much less listen through. There are a lot of wonderful things in there. Of these, I recognize a good portion of the artists and composers, but many are unknown to me. It’s frankly overwhelming. Sometimes I’ll make a coffee in the morning and randomly play something by an artist I’ve never heard of, having no idea what to expect. Yet several months after the memory stick arrived, I have barely scratched the surface.

I’m not sure there’s a point to any of this. I have a couple thousand CDs and a few hundred vinyl albums. I also have a growing collection of multichannel SACDs, DVD Audio and Blu-ray audio discs, and literally hundreds of quad releases which have been generously shared with me over the years. Not to mention a burgeoning collection of HD audio files. In all honesty, It’s all probably more than enough to keep me going for the rest of my life.

Do I Need more new music? Probably not, yet I subscribe to Qobuz and still listen to new things every so often, but not nearly with the frequency I used to. Is it age? I don’t know. An old Far Side cartoon comes to mind. The scene is a classroom and in the front of the room is a kid with a noticeably small head, his hand raised. The caption reads, “Mr Osborne, may I be excused? My brain is full.”

That’s me in a nutshell.Monica Salamaso trio live

I’ve been a fan of Monica Salmaso for a number of years, first encountering her on a couple of albums by the now defunct group Vento em Madeira. This was a kind of super group of Brazilian artists which created unbelievably sophisticated, free and adventurous music, some of which seemed to be comprised of intricately written out arrangements, but according to Ms Salamaso, were completely made up and refined in the studio on the fly and then rigorously rehearsed. Yet the evolved arrangements are balanced with free playing, loosening up the music with a completely spontaneous vibe that entices the listener to revisit these albums. My favorite of the three albums put out by this group was Brasilia. All three are sadly out of print, but worth tracking down.

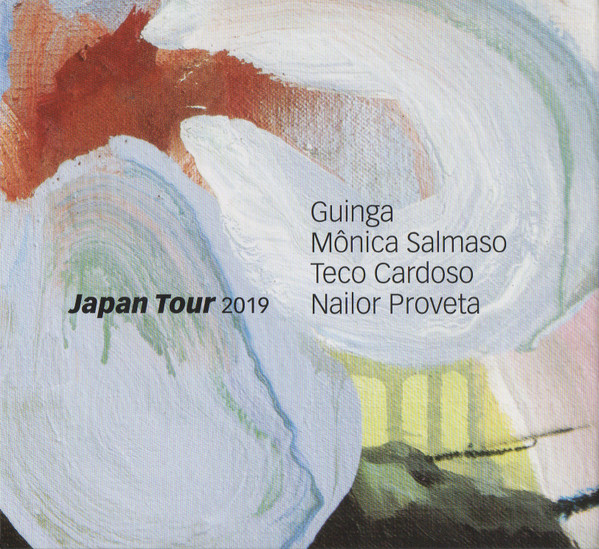

Two of the artists featured in that group were in the trio I saw last Saturday evening at the 222, a gallery turned performance space in Healdsburg California. Because of the yearly Brazil camp in nearby Cazadero, Brazilian artists sometimes perform in Healdsburg before heading home. This year, the trio of vocalist extraordinaire, Mônica Salmaso, Guinga, one of Brazil’s most celebrated composers and guitarists, took the stage with the amazing multi-instrumentalist Teco Cardoso on flute, alto flute, bass flute and soprano sax. This trio sounds like a chamber group that happens to play Brazilian jazz, (or perhaps the other way around.) The result was an intimate, passionate performance that pulled on one’s heartstrings one minute and swung madly the next. All three of these artists are virtuosos, but the secret ingredient that really elevates this music is the compositions of the incomparable Guinga. The trio played his compositions exclusively last Saturday night, with the exception of the encore. Guinga’s music is sophisticated both harmonically and melodically, and as complex as some of it is, it gradually gets under one’s skin.

Salmaso possesses an amazing instrument. Sensual, passionate and soulful, this isn’t your breathy Astrid Gilberto type singer (and don’t get me wrong, I like Astrid). Monica’s technique is anything but monochromatic, possessing a palette of colors that covers the entire rainbow of human expression. I only wish I understood the lyrics, because she performs with her entire being, investing her whole self in the stories told in these hauntingly beautiful songs.

Guinga is the consummate accompanist, laying down the backing with a sure hand and an effortless technique, an unerring rhythmic sensibility, all the while casually demonstrating an encyclopedic knowledge of the fretboard, which is always in service to the music. His style is the epitome of good taste. His writing melds the various Brazilian traditions, both folkloric and modern, sprinkling in classical motifs and harmony, occasionally borrowing from the language of Debussy, Ravel and Villa Lobos.

Teco Cardoso delivers a varied banquet of colors on his flutes and sax. He started the set on the rare bass flute, which he played exclusively for the first few tunes. He layed down deep, tasty solo lines, countermelodies and audible percussion parts played on the instrument’s keys. Teco seemed to favor the soprano sax for solos, each one a textbook example of perfect execution and conception, infused with fiery soul. His is a jazz oriented vocabulary, but he peppers it with folkloric flourishes and the result is utterly enchanting. At one point he brought a set of indigenous double wooden flutes, which I first heard on Egberto Gismonti’s classic Solo Meia Dio. But being a wind player, Cardoso took it up several notches, and mesmerized the audience with his bird calls and lovely melodic fills, instantly evoking the depths of the Amazon jungle.

Although the trio leaned heavily into slower, introspective pieces, make no mistake – this little group can really groove. Monica sometimes played pandeiro (and even a camping frying pan,) and really kicked up the excitement on the sambas.

I have a number of Salamonso’s albums. They are all quite different from one another. Some are quite densely arranged, as on her 2004 release, IaIa, and in contrast, her more recent Milton, which features Milton Nascimento’s compositions exclusively, is accompanied solely by master pianist, Andre Mehmari. I tend to prefer the less dense albums.

I searched to see if the trio I saw had any albums out, and the closest thing I could come up with was the Japan Tour 2019, which features the aforementioned three players with the addition of clarinetist Nailor Proveta. It’s a wonderful live performance which features a number of pieces featured in the set I heard, and really captures some of the magic of that memorable evening.

Romantic yet unsentimental, this music covers the spectrum of human emotion. I highly recommend exploring this artist and her talented compatriots.

Milton + esperanza

The new album with Esperanza Spalding and Milton Nascimento is a joyous affair, filled with unexpected sounds and colors that only these two artists could conjure. I believe it’s meant to be played all the way through, as the album weaves in and out of contrasting intimate tone poems and larger scale orchestrations, stitched together by little snippets of conversation filled with laughter, while Milton muses on his 60 year career in music.

When people used to ask me who is this Milton Nascimento, I would struggle to find a description. I used to call him the Beatles of Brazil, for his originality and commitment to his very personal musical convictions (and perhaps because Milton is such a huge fan of the Beatles,) but nowadays I refer to him as the Paul Simon of Brazil, for his continual search for new sounds and his intelligent, heartfelt lyrics. Milton is not merely a lyricist, but a true poet.

Over the course of his career, many artists of different stripes have wanted to work with him. Just listen to a personal favorite, his amazing album, Angelus. Here we find among others, the arranging skills of Gil Golstein, voices of James Taylor and Peter Gabriel, as well as contributions from jazz giants Herbie Hancock, Pat Metheny, Ron Carter and Jack DeJohnette, not to mention the exoticism of the unique instrumental quartet Uakti, all on one generous 80 minute long behemoth of a recording.

In contrast to the ambitious studio sprawl of Angelus, Milton + Esperanza is a more focused, intimate recording, made in the autumn of Milton’s life; in fact, most of the tracks were recorded in his home.

In Milton’s vocals, one can hear a lifetime of hard earned wisdom, which, although a bit rough around the edges, still communicate a depth that if anything, time has only honed and deepened. Think of Kenny Wheeler’s last album, Songs for Quintet – That’s how Milton’s voice comes across – aged yet burnished to a fine finish by time.

Besides revisiting a number of Milton’s tunes from his storied career, Esperanza contributes four of her own tunes and vocals on a number of duos, mostly sung in Portuguese, as well as some solidly supportive bass playing. The album also includes a beautiful, somewhat avant garde version of the Beatles A Day in the Life, as well as a cover of Michael Jackson’s Earth Song. It concludes with a cover of a Shorter song, When You Dream. Originally sung by Shorter’s daughter on the landmark album Atlantis, it is sung here by Shorter’s widow Caroline, who Shorter had urged to sing more often, saying the world needed to hear her voice. I think he would’ve been proud of her performance.

Esperanza seems to have a natural affinity for her elders, something she says goes all the way back to her childhood. She was good friends with Wayne, and collaborated with him in his last years on the opera Iphigenia, in which she also performed the lead role. And of course, there’s that special connection between Wayne and Milton, captured so beautifully on the timeless Native Dancer. Considering their mutual friendship with Shorter, it seems that much more fitting that Spalding would make this album with the elder artist. Indeed, at the heart of this project is the friendship between two artists from two different generations, brought together through their shared love of the music. The love and affection between the two is palpable on every track.

Speaking of Paul Simon, Simon sings on the Nascimento tune, Um Vento Passo, in Portuguese no less. Somehow, two of the most different voices in the world find a way to blend together seamlessly. Other guests include Dianne Reeves and the Brazilian guitar maestro Guinga. Multi winds instrumentalist Shabaka Hutchings appears on the album as well, adding beautiful colors to this richly textured recording.

Special mention should be made of the recording itself, which I’m guessing makes use of some of the latest psycho-acoustic 3-D effects. Even though it’s not mixed in surround, it seems to swirl around the room and immerse the listener. I actually had to check my rear speakers to see if they weren’t playing.

This album was obviously a labor of love, and is a fitting tribute to one of the most distinctive artists Brazil has ever produced.HERE is a lovely 20 minute live Tiny Desk concert with special guests, filmed in Milton’s home.

Stuff I’ve Been Listening To

I’ve been listening to the new Giovanni Guidi album, A New Day a lot, and had written a detailed review to post here last week. Unfortunately, due to a freak accident, I lost the file just as I was about to post it. While not inclined to write another detailed review, I will just say here that it is an exquisite album which starts right out of the gate with a couple of dreamy rubato tunes in a row, setting the atmosphere for this largely introspective, ruminative recording. This album features some really nice writing on Guido’s part, with the exception of a free group improvisation and a distinctly abstract version of the standard, My Funny Valentine.

Guidi always sounds great, and this outing is no exception. There are a few pianists out there as consistent as Giovanni Guidi. The same could be said about bassist Thomas Morgan, who seems to be appearing as a sidemen these days on a lot of records I like. The real surprise for me here was tenor sax master James Brandon Lewis, who I had not heard of before this record. Lewis is an unerring melodicist, and doesn’t seem to play a note he hasn’t completely internalized. Last but not least, drummer Joao Lobo keeps it all moving, with his subtle colors and when needed, solid groove. The album ends with the marvelous piece, Wonderland, which starts out with a rubato melody played in unison on piano with Lewis on sax. It’s a wistful, yet optimistic tune, vaguely reminiscent of some of Jarrett’s writing for the European Quartet. Eventually it goes into 3/4 time and a simple yet effective modulating Lydian progression becomes a vehicle for joyful improvisation which builds and then takes us back home to the lovely rubato intro melody.

I am also revisiting a couple classic PMG albums I recently bought in SHM SACD format. The first (aka White Album,) album has always been a favorite, and it sounds only marginally better in SACD format. Of all the new Japanese PMG SHM SACD reissues, I would say OffRamp sounds the best of this lot, but then, the original album already sounded pretty darn good. I already had the earlier SACD issue of Travels, which definitely benefitted markedly from the transfer and is still a favorite, especially in this format. Worth tracking down that one.

Incidentally, none of these SACD reissues are remasters, and honestly, they are not a huge upgrade in terms of SQ. I have always thought that PMG was given short shrift sound-wise on these early group albums, and I’ve never understood why they weren’t remastered, or better yet, remixed (doubt either will ever happen.) The same goes for Bright Size Life, which I also bought as a new SHM SACD. This one fared the least well of all these newish SHM SACD releases. Not that great recording in the first place, and there’s just not a whole lot of definition to recapture at a higher sample/bit rate, because it just wasn’t there in the first place.

Speaking of Pat Metheny, I’ve been listening quite a bit to the new solo baritone guitar recording, MoonDial. I’ve really been digging it. It has a number of new Metheny compositions, as well as a lovingly rendered version of Here, There and Everywhere, which modulates a few of times in a very subtle, tasty way. Metheny also manages to breathe new life into the Chick Corea composition, You’re Everything off of the iconic Return to Forever album, Light as a Feather, taking it all the way from the original uptempo samba down to an introverted ballad. And it really benefits from the reinvention. Metheny finds all kinds of sweet harmonic nooks and crannies to caress in this little gem. Listening to it at this slow tempo, one realizes just how beautiful this tune really is. He also puts together a really nice medley of Everything Happens to Me and the Bernstein (West Side Story) composition, Someday. At this stage of his career, Pat Metheny can take a tune like the much covered Londonderry air, a.k.a. Danny boy, and remake it into completely fresh. With its ingenuous chord substitutions, this reharmonization exceeds most versions I’ve heard in terms of harmonic invention. Metheny also explores two other standard ballads, My Love and I and Angel Eyes, breathing new life and substance into both of these chestnuts. The engaging, highly Metheny-esque title track bookends the album, giving a full reading at the beginning and then returning as a short reprise at the end of the album.

Perhaps one of the best things about this album is the sumptuous sound of the guitar itself. Linda Manzer, who has been Pat Metheny’s luthier for decades, has really outdone herself here. As great as the baritone guitar sounded on the first solo album, One Quiet Night, a couple years ago Metheny asked her to build him a new guitar for the DreamBox tour, one which was specifically designed for nylon strings. Apparently it was quite difficult to locate a set of nylon strings that would fit a baritone guitar, and Manzer had to scour the globe in order to procure a set. All I can say is, the search was worth it; The guitar on this album is the perfectly balanced electro/acoustic blend. It has the warmth, detail and intimacy of an acoustic nylon, but also possesses the deep bottom and color of an electric. It fills the entire room, and one sometimes gets the sense Metheny is working with a portable orchestra in a guitar case.

Metheny doesn’t feel the need to show off on this record, instead choosing understatement and subtle fretwork which underscores the beauty of the instrument and brings out the lyricism of the chosen originals and covers. This is a very laid-back album which suits my mood these days, when I find myself seeking solace in quiet down tempo music. And this gem fits the bill perfectly. It’s comfort food for the soul, but not without its nutritional benefits.

“Music For Black Pigeons“

I bought my copy of „Music for Black Pigeons“ a number of months ago, watched it and was very moved by it. But it wasn’t until I revisited it yesterday during a break in a session of free playing with a talented percussionist that I fully appreciated it. Watching it with a fellow artist allowed me to see it with fresh eyes and ears.After viewing it a second time, I realized just how artfully this film is executed. It is more than just merely another music documentary; it is really a humanistic art film that focuses on aging, love and the shared passion for artistic collaboration. And of course, always the beautiful music.

While the film centers on guitarist Jakob Bro, the beating heart of this film is in the elder players who recognized his talent and wanted to play with the young Danish maestro. Structurally, the film takes its time, setting the scene for each location, lingering on buildings or street scenes, giving the viewer a sense of place and atmosphere before diving into the more intimate scenes.

The brilliant direction and editing takes advantage of the nearly 15 years of filming, exploring the themes of aging and the palpable love between collaborators, which in many cases resulted in lifelong friendships. All of this moves back and forth in time, revealing the personalties of each player through fly on the wall moments in the recording studio and on stage.

Punctuating these vignettes are revealing interviews with many of the players. Unlike many such films, the questions are probing, the answers provocative and often profound. As a lifelong musician with a long career in music, I found the artists’ struggle to answer these questions relatable and incredibly insightful.

There are so many highlights it’s hard to pick just a couple. I loved every moment Lee Konitz is onscreen. He is painfully honest and real, and his humbleness is completely genuine. Here is a guy who has been a part of so many scenes in several important eras, and still demonstrates a childlike beginner’s mind in relation to Bro’s contemporary approach to modern music, and even though he admits to not fully understanding what’s going on, nonetheless embraces the moment and throws himself into the music wIth spontaneity, imbuing every note in each solo with meaning, great heart and wisdom. Just watching the love and recognition amongst his peers, especially the look on Jakob Bro’s face as Lee overdubs a brilliant solo that can only come from a lifetime of dedication to his craft, is worth the price of admission.

I also loved the portrait of nerdy bassist Thomas Morgan as we watch his morning regimen, getting on the PC (programming in DOS no less,) to cue up an incredibly diverse program of music while he performs his morning stretches and his own peculiar variations on yoga postures, then selecting his clothes for the day. Delightful as is his quirky interview, which starts off with what has to be one the longest pauses in documentary history.

There are a great many musicians featured in this documentary. From memory and in no particular order: Bill Frisell, Thomas Morgan, Joe Lovano, Joey Baron, Paul Motian, Jorge Rossy, Craig Taborn , Palle Mikkelborg, Arve Henricksen, the late John Christiansen, Mark Turner, Andrew Cyrille and several others. A number of these artists are also interviewed, as well as the ones I mention here.

I don’t want to give too many things away here for those who haven’t had the pleasure of viewing this film, but I will also add that the beautiful scene with Manfred Eicher in the studio with Bro and compatriots recording Bro’s tune dedicated to Tomacz Stanko, really touched my heart. The camera wanders around the control room and rests on a picture of a younger Eicher and Stanko and other photos from a decades long association. In his interview, Manfred Eicher tries to express his feeling about his many years in the recording studio with Stanko, finding himself at a loss for words, before he is finally overcome with emotion and unable to continue.

In the end, this film is a poignant portrait of elder musicians with really young hearts who are still willing to explore the edges of creative boundaries, playing with a younger generation of open creatives, and finding much to offer as well as to receive. The film also makes it clear that it’s the music that transcends the disparities of race, age, gender and cultural origins. All of these differences are ultimately superficial when artists come together with a common purpose.

I want to add that this film looks absolutely gorgeous; even though it was released on DVD, it looks as good (and sometimes better) as many of my BluRay discs. I honestly don’t know how they pulled that off, but they did. Also the sound, which is in Dolby Digital, sounds equally amazing, as good as many uncompressed Master Audio HD soundtracks in my Bluray collection.

A Tale of Woodpecker Woes

Acorn Woodpeckers are a common Northern California sight. With their distinctive red caps atop their heads, these adorable, agile little birds have been chattering in and around the oaks that surround my woodland retreat since I moved to the hills of Forestville, CA, some 25 years ago. I have always enjoyed watching their antics – such busy, comical characters. I also love listening to their humorous laughing calls. They are active, energetic and good natured creatures. They are clannish and extremely social; families of acorn woodpeckers live and work together, their sole purpose in life (beside procreation) being to gather and store acorns. Their strong beaks and neck muscles allow them to easily pierce thru most wood; they spend a good part of their lives drilling large holes in which to store their precious bounty.

As winter approaches, they are busy picking up acorns and piling them up, huge aggregations mounting under a nearby telephone pole that is so riddled with holes the power company had to replace it. They kindly left part of the old one attached so the woodpeckers could continue their one-pointed mission.

After the acorns are stacked up and the holes are drilled for the new crop, the woodpeckers get busy picking them up one by one and slotting them into each hole. It is a painstaking, time-consuming activity, one they never seem to complete.

I used to think the acorns themselves were food for the critters, but I was wrong: acorns aren’t really meant to be eaten just as they are. The acorns attract small insects, which burrow into them. When they are full of yummy bugs, the woodpeckers retrieve the acorns and consume them. It’s a marvel that they can remember where every single one is.

There used to be a season for each activity, but with climate change, the acorn woodpeckers seem to be focused on nut gathering year round. Apparently, there can never be enough holes drilled or acorns socked away for a rainy day.

One fall, the acorn woodpeckers decided my home was fair game. They started drilling into the trim pieces on the sides of my house. Whereas I always enjoyed their antics, I soon realized I had to draw a line in the sand. This was war.

I puzzled over my options. I half-heartedly threw pebbles at them. I banged on the walls and windows. Nothing deterred them. Then I got a brilliant idea – a slingshot. I realize this sounds cruel, but my intention wasn’t to harm them, just to scare them away. I did my research and discovered there were little clay pellets used for target practice, so I purchased an intermediate slingshot along with a large bag of these lightweight pellets.

At first I was an awful shot. But eventually I got good enough to hit the metal downspout at the corner of my house where they were pecking away. That scared them off, at least for a while. I would sneak down the side of my house and aim for the downspout. One day, while I was engaged in that activity, just when I was about to take my shot, a tiny face peered around my neighbor’s fence and made an uncharacteristic repetitive screeching sound, alerting the woodpecker pecking on the corner of my house – it immediately flew away. I realized they were working together on this; the little fuckers now had spotters.

In all the years I have been battling these persistent creatures, I have only hit one once. When I did hit the little guy, he fluttered his feathers indignantly and turned towards me with a look that seemed to say “How dare you?!” He then flew away unharmed. That kept them away for a while. But they soon returned.

It became clear that my efforts with the slingshot were yielding diminishing returns. The clever little monsters anticipated my every move. They warned one another and were so aware of my presence, I could barely get off a single shot.

Thinking perhaps my trim pieces were old and easily penetrable, I replaced them with harder wood. But the new ones I installed (at no small expense) did not stop them for a second.

So I developed a new strategy. I decided, if they were going after me in my home, I would go after them in theirs. I began going out on my deck and taking pot shots at them hanging about in their favorite staging grounds, several venerable oaks in my backyard.

As I was still a terrible shot, I didn’t hit them in their trees or even come close. But I was at least good enough by now to annoy them, and after a while they would leave those trees, at least for a while. But they always came back to peck on my house, especially when I was out. I found that consistency was the key. If I responded promptly to each and every attack, going after them “where they lived”, they would eventually get the idea. It sort of worked.

After a hard day’s work, these creatures like to congregate at twilight in a spreading oak tree on my neighbor’s property. There they socialize, laugh at each other’s jests, get into arguments and presumably recount the day’s exploits. “That was a tough hole to make”, “ That asshole human isn’t worth the trouble. Doesn’t he have anything better to do with his time?” “Those squirrels are taking over this tree – we must chase them off!”

Indeed, the squirrels are the acorn woodpeckers real nemesis -after all, they are competing for the same treasures. Although to be fair, the acorn woodpeckers are the real trouble makers. Each day I watch the poor squirrels just trying to live their lives, getting kamikazied and chased away by sharp beaked dive bombers. The beleaguered animals are rarely left alone to enjoy themselves. Oftentimes after being harassed, these poor creatures take shelter on my upper deck, the only place they are safe from the attacks. There they take in the sun and relax, safe at least for a little while from the constant harassment.

Over time, I began to identify with the squirrels’ plight. Like mine, their safe homes were also being unjustly invaded. I surmised there really were enough acorns to go around for all. But acorn woodpeckers are an obsessive lot and definitely not socialists; they are survivalists and, worse, hoarders. For these creatures, there can never be enough acorns and never enough holes in which to deposit them. I began to develop a real empathy for the squirrels. And when they wearily climb onto my deck railing, I give them a sympathetic wave. It was when (I swear) I saw one conspiratorially wink at me that I suddenly knew what the next stage of my woodpecker strategy had to be: a squirrel/human alliance.

Those red-capped fuckers will never know what hit them.

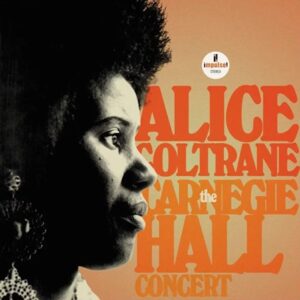

Alice Coltrane Carnegie Hall Concert

First of all, I find it amazing this fine 1971 concert recording has never seen the light of day. This set was part of an eclectic concert lineup that could only have been programmed in this period of odd juxtapositions. The evening this was recorded, Alice Coltrane was opening for none other than Laura Nyro and the Rascals. Her landmark album, Journey in Satchidananda had just been released and Impulse was hoping for a boost on record sales and perhaps a live companion album to the new studio release.The lineup for this band is impressive: Besides the inimitable Ms Coltrane on harp and piano, Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp are in the front line, both Cecil McBee and Jimmy Garrison are on bass, with no less than three percussionists as well, Ed Blackwell, Clifford Jarvis and Kumar Kramer. Together, what a joyful noise this band makes!

Alice Coltrane was so far ahead of her time, this music still sounds startlingly fresh today. Unlike her recordings, the drums and percussion are in the forefront here, thus giving this recording a more propulsive vibe than her studio albums which feature harp.

For the first two pieces, swirling harp glissandos and percussion bathe the listener in waves of beauty, lulling the listener into a meditative state, that is, until John Coltrane’s Africa rouses the audience with a potent percussion ensemble solo, followed by Coltrane’s pounding piano chords and dueling growling solos from Sanders and Schepp. After the sax solos comes a powerful Coltrane piano solo following by an explosive ensemble drums and percussion solo. The mood suddenly becomes ruminative as Garrison and McBee take the floor quite literally with an extended bass solo. The bass solos eventually evolve into a low end groove that even briefly gets the audience clapping along. One of my favorite moments is when Coltrane comes back in with a grooving ostinato, followed by Sanders and Shepp’s vocal-like screams – shouts of joy and pain explode across the aural firmament. The concert closes with another John Coltrane composition, Leo, which takes the fierce ecstatic intensity up another level, Sanders and Schepp channeling the late sax player’s cosmic wails in a cacophony of deep spiritual yearning.

As wonderful as the solos are, perhaps the best moments are when the band is just in playing together in the sound space and grooving. This is trance music of the highest order. It really takes the listener on a journey into cosmic bliss.

In a way, this release seems perfectly timed. There has been renewed interest in Alice Coltrane’s music in recent years and for good reason: in these chaotic, divisive and violent times, we need this music more now than ever. Recently, there have been several tribute concerts in the US. The most notable is harpist Brandee Younger’s 4 night residence @ SF Jazz, where one evening she even brought in a small string section to perform some of this music. It’s great to see the tradition carried on.

When I was a teen, I was drawn to this music without knowing why. Something in my soul knew I needed this medicine, for medicine is exactly what this music is. This kind of spiritual jazz has always had a special place in my heart. This album is a wonderful gift to those of us who grew up with this music and a great introduction to the uninitiated. Sound quality is fantastic, especially in Hirez.