Uncategorized

One Beat

here is something suiting to Brian’s post on musical hybrids: a one-month residency of 23 young ‘world’ musicians from all over the globe under the heading of KINSHIP + GATHERING at the Avalon Farm Music Institute, New Hampshire, U.S.

It celebrates the spirit of kinship in our practices and lives. Focusing on both physical and conceptual spaces that serve as sanctuaries for connection and belonging, this residency invites fellows to uncover the threads that weave us together, recognising the inherent strength and beauty found in the tapestry of community. Via my personal connection Kateryna Ziabliuk to this residency, i hopefully can post some interesting observations. Here is an overview of the participants and link to the organisation.Participants are from a greater variety of countries: India Nepal Kazakhstan Ghana Indonesia USA Japan Argentina Egypt Turkey Ukraine Kenya Brazil Colombia Nigeria Cuba Senegal Pakistan

Up to your imagination how this could work (out) in the hands of a present young generation. To be continued …A Spontaneous Discussion of Musical Hybrids

[I recently had a discussion on social media with an iconoclastic instrument inventor who had a lot of strong ideas about the state of today’s music and the industry itself. One thing he touched upon was the uselessness of categorization of musical styles. He didn’t like the term “World Music” because he felt every music on the planet was in a very real sense, “World Music.” How could I not agree? What follows is a short essay I wrote when he suggested that not enough cross-pollination is going on in today’s musical realms. He also asked what it might’ve been like if European composers had, for instance, incorporated Indonesian music in their orchestral works.]First of all, in my opinion, the term “World music” is a perfectly fine way to describe music from around the globe. I have no problem with it and it sure beats the term “ethnic”. In truth, I consider all of these categories as arbitrary, and are essentially meaningless, as for the most part they don’t convey any useful information, and are created by suits to describe music primarily so they can sell it. A lot of contemporary artists don’t fit neatly in a pigeon hole.

There’s a lot unpack in your comment, but I’ll just say this: cross cultural pollination is exactly what is happening today and it’s never been more vibrant.

And it goes back a long way:

In fact, European composers did exactly what you have suggested – incorporate gamelan music, and as early as the late 19th were influenced by it. Debussy is a good example: when he first heard a Javanese gamelan at the Paris World Fair in 1889, it totally flipped him out and it influenced his work, especially in pieces like Pagodes.

The first wave of the influences of different cultures always seems to start out as a passing, rather shallow toe dip into foreign waters, usually followed by a much deeper dive. For example, in the European dominated symphonic traditions, we later find composers like Colin McPhee, who lived in Bali for a number of years in a hut in the middle of a rice field, with an old upright piano, and wrote some magnificent music.

in the 50s Lou Harrison, who also studied Balinese and Korean music, composed music for both gamelan and western ensembles. He incorporated some of the Balinese techniques such as kotecan (interlocking parts,) into his chamber music compositions. Check out his wonderful Concerto for Violin, Piano and Small Orchestra. Find the CRI version conducted by Leopoldo Stokowski if you can. A contemporary of Harrison, Henry Cowell was another pioneer in bringing the music of Persia and Asia into Western music.

Also, Jody Diamond of Gamelan Sekar Jaya fame comes to mind. Along with Ingram Marshall, she became an important composer of new music for Gamelan. There is also a new generation of Balinese composers who have in turn been influenced by western composers. There are countless examples of this kind of thing. Indeed, today we live in a world where cross cultural pollination is no longer rare, but in fact, the norm. It’s literally everywhere, in pop, jazz, electronica, classical etc. In a way, this hybridization is the cornerstone of 21st century music. It’s a huge subject, and I’m only going to focus on jazz for the rest of this piece.

Jazz is an art form that started right out of the gate as a cultural hybrid, in this case primarily a blend of African music/rhythm and European harmony, and also soon incorporated popular music from the American songbook, which was sourced mostly from show tunes and films. Later, artists like Dizzy Gillespie became fascinated with Cuban music, and thus began a longstanding tradition of cross pollination between two cultures that is still vibrant today.

The same thing holds true of American jazz musicians like Stan Getz and Charlie Byrd, who started hanging out and playing with Brazilian musicians in the “first wave” in the 60s, but once again, it quickly became a two way street, morphing into an ongoing feedback loop where at a certain point it became difficult to parse who was influencing whom.

Artists like John Coltrane and Miles Davis experimented with incorporating Indian music into their music in the 60s and early 70s. After all, jazz being an improvisational tradition, it seemed only natural for western jazz artists to start playing with Indian musicians. Later, artists such as John McLaughlin (who seriously studied the Raga and Konecal systems) and Indian tabla master Zakir Hussein, who helped bridge the cultural divide from the Eastern side, came together to form Shakti, a true east/west collaboration that remains active today. Of course there were earlier experiments. The much earlier collaboration between Ravi Shankar and Yehudi Menuhin comes to mind.

Another Miles Davis alumni and one of the founding members of Weather Report, Vienna born Joe Zawinul always brought together musicians from all over the world into his bands, which allowed each artist to bring his or her individual cultural voice to the table. I have always thought of Zawinul as a visionary, not just because of his wonderful musical contributions, but because of his utopian vision of a world in which each culture remains unique and distinct, yet comes together to create a harmonious whole.

And any discussion of hybrid music which blends the influences of different cultures would be incomplete without mentioning Paris born Vietnamese virtuoso guitarist/composer Nguyen Le, yet another cutting edge musician who has created a kind of “world jazz” that’s entirely unique, collaborating with African, Moroccan, Vietnamese, Sardinian and American artists (just to name a few,) to create his own unique hybrid.

Cuban piano/keyboardist Omar Sosa, has become an ambassador of unique collaborations with artists from other cultures. Pictured above is his SUBA trio with African kora master, Seckou Keita and Venezuelan percussionist maestro, Gustavo Ovalles. Sosa exemplifies the healthy exploration of searching for and finding common ground between cultures.

Tigran Hayasman is another interesting example. As a young boy living in Armenia, he started off as a classical pianist but soon became fascinated with jazz. He was a prodigy, and while still in his teens, won the Thelonius Monk competition. But Tigran quickly outgrew the constraints of the jazz label and started making music which is impossible to categorize. He loved the complex time signatures of his native country and soon incorporated them into his own compositions, combining traditional folk melodies with heavy metal, prog rock, electronica, hip hop, pop and classical music. The result is hard to describe, and while I realize it is an acquired taste for some, I find it challenging, often quite beautiful and staggeringly original.

Last, but hardly least, Oregon needs to be mentioned. To me they exemplify the essence of intelligent, passionate musical cross pollination. They effortlessly blended western contemporary classical, jazz, free improvisation, world music of all sorts, and in the early days at least, East Indian influences in particular, to create an emblematic hybrid that has stood the test of time. Indeed as the decades have rolled by, their importance has only grown in stature.

In this world of ours, which has gotten so much smaller thru technology, this kind of thriving collaborative community is only natural and ongoing in virtually all genres and subgenres.

The subject of cultural appropriation sometimes comes up in discussions like these. What I have learned regarding whether it is appropriate to borrowing from other cultures has a lot to do with the culture one is borrowing from, and the attitude of the person doing the borrowing. For instance, in Bali, my sense has always been that Balinese musicians are very open, and generally love collaborating with people from other cultures. They not only welcome it, they have a long tradition of embracing it. My own teacher in Bali once proudly played me a cassette of himself playing drums with a gifted young Australian blues guitarist. The whole time it was playing my teacher was proudly beaming at me. The Balinese people have always been open to experimentation; I once attended a performance in Bali in which all the musicians were sitting down at synthesizers instead of traditional acoustic gamelan instruments.

On the other hand, my longtime music mentor, who is friends with a number of musical luminaries and considered to be one in certain circles, once told me a story about a famous artist who had borrowed an mbira part which he incorporated into a contemporary track. Apparently, when the African artist who had played the mbira part heard the finished track, he broke down in tears, because to him this was sacred music, and it was being desecrated by being used in what he perceived to be a secular context.

At one point, I was considering taking up the traditional African mbira myself, and the teacher I asked for lessons snubbed me because she felt that I was going to use it in my own music and that I didn’t show enough respect for the sacredness of the tradition in order for her to accept me as a student.

My take on cultural appropriation is that one should always ask one’s teachers and fellow musicians how they feel about incorporating their music into one’s own. That being said, my own experiences have shown me that for the most part, musicians from other parts of the world are flattered when an artist shows interest in their musical culture.

King Crimson: Sheltering Skies (Fakten und Erinnerungen)

27. Juli 1982 an der Cote d‘Azur. King Crimson touren mit dem neu formierten Quartett (Fripp, Belew, Bruford, Levin) durch Europa, meist zusammen mit Roxy Music, und machen Station in Fréjus. Wenn Platten besprochen werden, besteht ein wiederkehrendes Lieblingsmotiv der Musikkritk in dem Ausdruck „dead quiet vinyl“. Nun, diese 200 Gramm-Pressung kommt dem nahe – die komplette Aufnahme ist von roher Direktheit, hyperrealistisch fast, und wer die studiotechnischen Brillianz und Balance der drei Platten des Quartetts kennt, nimmt hier erst mal Adrian Belews Härte 10 auf der elektrischen Gitarre zur Kenntnis, in den ersten dissonanzfreudigen Minuten dieses Doppelalbums. Das klingt und ist knallhart, kein Schmeichler zum Auftakt, und kein Röhrenverstärker würde für mildernde Umstände sorgen. Aber die Ohren adaptieren die Wucht. Das Quartett belegt mit diesem Aufritt einmal mehr, dass King Crimson wohl die einzige Gruppe aus der Ära des Progressiven Rock war, die sich vom Punkvirus äusserst kreativ inspirieren liess. Der Fripp-Faktor! Obwohl seine neuen Kompositionen einmal mehr ausgeklügelt, detailversessen und anspruchsvoll waren, wird hier rein gar nichts notengetreu abgeliefert. Oder makellos reproduziert. Alles kann jederzeit Feuer fangen. Und fängt Feuer. Deswegen macht hier auch eine andere Lieblingsformel der Musikkritik Sinn: play it loud!Listening to this late summer evening music

at the Cote d’Azur on July 27, 1982

brings back memories.

The same band, King Crimson,

a week (or so) later. Nürnberg.We were lying on the grass,

we were bloody everything,

our faces east, our feet dancing,

Robert, Tony, Adrian, Bill playing Heartbeat“ –

at that moment, night included,

eternity (in decay mode),

the gloom of the moon on your nakedness,

later, in that odd old hotel,

windows to the heavens,

i can still feel your heartbeat (in the song),

and though everything was loss later,

pictures running on empty,

in circles through my mind, it doesn‘t matter.

- Erste Veröffentlichung eines King Crimson-Konzerts aus den 1980er Jahren auf Vinyl / Erste eigenständige CD-Veröffentlichung des kompletten Konzerts / Das komplette Konzert aus Fréjus, Frankreich, aufgenommen von den Original Mehrspurbändern von Robert Fripp & Brad Davis. / Die Aufnahme von ‚The Sheltering Sky‘ aus Cap d’Agde ist ebenfalls enthalten / Vinyl geschnitten von Jason Mitchell bei Loud Mastering / Gepresst auf 200-Gramm-Vinyl und präsentiert in einem Gatefold-Sleeve / CD gemastert von Alex R. Mundy bei DGM / my little essay on Robert Fripp‘s boxset „Exposures“ can be read HERE, and end with that poem above, simply titled „September 1982“

The Grand Wazoo im Transistorradio

Es gab in meinen zwei letzten Jahren an der Oberschule ein Transistorradio in der Küche, und da spielte eines Morgens Frank Zappa. Es war die Zeit seines fulminanten Jazz-Rock-Epos „The Grand Wazoo“, und bei diesem unvergesslichen Liveaufritt gab ein gewisser George Duke den Keyboardmeister, der Frank Zappas vertrackten Synkopen in jeden hintersten Winkel und darüber hinaus folgte. Ich hatte grossen Spass an dieser Musik, zumal ich meinen leichten „Kater“ vom Vorabend mit zwei grossen Gläsern Milch und einer Alka-Seltzer gut in den Griff bekam. Was für eine verspielte, wandlungsfreudig rockende Big Band! Frank Zappas Hang zur Satire sorgte dafür, dass ich das Opus irgendwo zwischen den Marx Brothers und Monty Python einsortierte. Nie in meinem Leben liess ich auch nur den geringsten Lacher los beim Ansehen eines Films der britischen Komiker, während der anarchistische Humor von Grouch und Co. mich meistens leichtfüssig einfing. Es passt dazu, dass ich „The Grand Wazoo“ seit damals mit einem gewissen Hin- und Hergerissensein hörte: enweder liess mich die ausgefuchste Klangkunst kalt, oder sie packte mich mit ihrer immensen Spiellaune, die, live dargeboten, noch manch freien Extralauf und Schabernack bereithielt. Zuletzt hörte ich das Album in wunderbar gelungenem Surround, und das Pendel schlug wieder aus in Richtung der unbändigen Freude von einst, anno 1972, in der Küche mit dem silbernen Toaster, dem kleinen Metallradio, George Dukes irrwitzigen Läufen, meinen 17 Lenzen, und zwei rasch heruntergestürzten Milchgläsern!

La Selva de los Relojes

There are a couple of album covers with my live drawings in the recent past among them also a c over for LA SELVA DE LOS RELOJES of young Catalan cellist Pau Sola Masafrets (living and working in The Netherlands). He gave me the recordings he made with his group comprising Björk Nielsdottir (vocal), George Dumitriu (violin), Marta Warelis (piano) and George Hadow (drums) that he wanted to release as an album and asked me if I can produce a drawing for the album cover. I can, I said, but i can only do it when the music is played live. Pau then organised a private session I joined with my live drawing. This is documented in a very nice video made by Beatriz Lerer Castelo. The music works with texts of Frederico Garcia Lorca and Albert Einstein.

V I D E O

The music of the album you can find on bandcampLichtBilder

In der Fotografie geht es für mich in erster Linie um das Fangen von Licht und Lichtfall. Ich beginne den Tag regelmäßig damit. Die Variationen des Lichts an demselben Ort, auf der gleichen Strecke zu verschiedenen Zeitpunkten sind erstaunlich unermesslich und damit eine ständige Herausforderung, etwas von dem Faszinierenden davon einzufangen. Was ja höchstens andeutungsweise gelingt. Licht ist eben viel fliessender (und schneller) als z.B. Töne, Klänge es sind. Getrieben von einer Lichtvorstellung, einem tieferen 'Lichtwunsch' versuche ich dem immer wieder näher zu kommen. Festhalten oder festlegen ist dafür nicht der passende Ausdruck. Licht ist ja immer in Transition. Große Fotografien stellen ja auf verschiedenste gestalterische Weisen einen verstärkten oder subtilen Eindruck dieses Transitionellen her. Beim Fotografieren stehen für mich nicht unbedingt Objekte im Vordergrund, sondern das Spiel des Lichts und das Einfangen desselben, das Spiel des Lichts, das Objekte in spezieller Art'hervortreten' lässt oder verschwinden lässt. Manchmal kann man Objekte in der Fotografie ja auch gar nicht (wieder)erkennen, oder sie können übertrieben zum Vorschein kommen. Es gibt da einen großen Spiel-Raum und Arten von Stimmigkeit. Wobei der Ausdruck 'Stimmigkeit' ja interessanterweise eine vokale Herkunft hat.

Ich werde regelmäßig Resultate meiner täglichen Lichtjagd im changierenden Lichtfluss hier einbringen, einmal aus der Serie "Musical Gazes" und etwa der Serie "Otheristan".

A record to spend a night with

….and THIS is from an album to spend day and night with…

….das sind oft gehörte Umschreibungen, für bestimmte Alben die Nacht zu empfehlen, den Somntagmorgen, oder sonstige lauschige Nischen der Zeit – „modern mood music“ und ihre idealen Zeitzonen. Ich war ganz froh, den Film „Music For Black Pigeons“ abends gesehen zu haben, und einen Tag später fiel mir auf, dass mir eine Platte des Jahres 2023 vollkommen entgangen ist. Ihre Aufgabe, lieber Leser, besteht nun darin, sich das Album „Once Around The Room“ von Jakob Bro und Joe Lovano zu besorgen, das mit den Hitchcock-Vögeln auf dem Cover, und die ideale Zeit zum Hören herauszufinden….(m.e.)

Neue Herumtreiber und ein dicker Hund – eine kleine Geschichte voller Seitensprünge zu den frühen Jahren des American Analog Set

„What a fucked-up city. Imagine how many people out there are fuckin‘ right now man, just goin‘ at it? (Slater, looking at the panoroma of Austin at night, in Dazed and Confused)

No, they certainly do not rock. One listen to The American Analog Set’s debut, The Fun of Watching Fireworks, released last year on Trance Syndicate/Emperor Jones confirms that loud and… well, not so loud — but clear. Like a whisper in a hushed room. And if you’ve ever seen the local quartet live, whether crammed into the corner at the Blue Flamingo, or under the neon lava glow of the Electric Lounge sign, hushed is the atmosphere you’ll find — where every beer bottle dropped into a garbage breaks the mood like a telephone call during sex. (Austin Chronicle, 1997)

Selbst damals in den Neunzigern waren die Republikaner, die Rednecks, ziemlich präsent in Austin, Texas. Lucinda Williams kannte dennoch ein paar nette Menschen dort. Wie dem auch sei, zu all den Orten, zu denen ich gerne via Zeitmaschine reisen würde, zählt, in milder Rückschau, neben London 1965, Santa Monica 1967, seit kurzem auch, Austin, Texas, 1996. So etwas passiert Musikjournalisten eigentlich nur, im puren Spiel der Fantasie, wenn sie in den Sog einer Kulturszene geraten wollen, die mal grosse Wellen geschlagen hat. Und glauben Sie mir: grosse Wellen hat vor der Jahrtausendwende in Austin gar nichts geschlagen. 1993 wurde dort Linklaters Coming-of-age-Streifen „Dazed and Confused“ gedreht, eine Zeitreise ins Jahr 1973, so beknackt, dass sie fast schon liebenswert rüberkommt. Aber ein Auslandsjahr dort in Austin, bei einem lokalen Radiosender, und ich hätte mich wahrscheinlich in Lisa Roschmann verliebt.

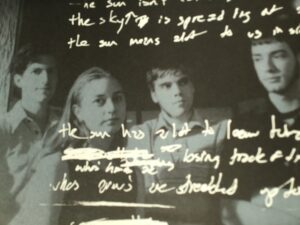

Und was hörte man so in der Independant-Szene, damals, in Austin? Stereolab waren gesagt, dann extraordinaire Band mit Baritonsaxofon, auch ein paar lokale Helden, und, die unangestrengtesten von allen, The American Analog Seit. Als zu Beginn dieses Jahres die Archivmeister der Numero Group auf fünf fabelhaft editierten und anzuschauenden Langspielplatten den Output der Analogen unter dem Titel „New Drifters“ veröffentlichte, war das Echo, wie zu erwarten, nicht riesig, aber voll des Lobes, in einschlägigen Magazinen und Blogs. Das beiliegende grossformatige Heft füttert uns mit Schwarzweissfotos aus den „salad days“ dieser jungen Band, in deren Musik ich ohne Anlauf versank, seltsam aufgehoben, aufgelöst.

Sie waren mir komplett entgangen, sonst hätten die playlists meiner Radiosendungen damals ein wenig anders ausgesehen. Immerhin hatte ich die samtweiche Nachtmusik von Morphine im Programm. Über die Seiten des tollen Beihefts verstreut, neben den Bildern, viele „lyrics“, durchweg handgeschrieben, manchmal unscharf, voller durchgestrichener Linien – perfekt in die Fotosammlung jener verschwundenen Jahre eingearbeitet. Zwei aus der Band waren ein Liebespaar, und es gab Gründe, dass Lisa ausstieg, die mit E-Piano, Flöte, Orgel, Stimme, zum Zauber einer Band nicht unwesentlich beigetragen hatte, der man Unrecht tut, wenn man sagt, sie würden alle, und das höre man auch, Galaxie 500 kennen und die Velvet Underground. Da war mehr im Spiel als irgendjemandes Urklang, und fremdes Fahrwasser.

Ab einem bestimmten Alter kommt es eher selten vor, dass man einen Narren frisst an einer Band, aber mir ist das hier passiert. Wie damals, 1980, als ich eine andere Gruppe mit einer verhuschten Mädchenstimme erstmals hörte, Young Marble Giants. Ich bin ziemlich sicher, Lisa liebt „Colossal Youth“. Ich möchte mich dem Ende dieser kleinen Abhandlung – und ein „dicker Hund“ kommt noch – nähern mit ein paar Zeilen aus „New Drifters“, ich versuche es mal mit reinem Zufall: „…the girls will get reports on the hour / from boys on the catwalk by the tower / don‘t fret (?) the kids down at the record shop …“ Das ist jetzt nichts, was den Atem stocken lässt, eine flimmernde Tagebuchnotiz. Das Unheimlich-Flüchtige ist auf diesen fünf Schallplatten stets präsent eingesponnen in Ohrwürmer, stillstehende Zeit, Klangexperimente der sanften Art, melancholisches Verschwinden (exquisit hypnotisch) – und ein paar ernsthafte Gedanken über das Mysterium der Freude an Feuerwerken.

TIME MACHINE….MARGINAL MEMORIES…. SPOKEN OUT BY ANDREW KENNY FROM AMERICAN ANALOG SET…. SPRING 2002…. „The word on the street is that Lisa was married recently. Funny that. I guess my invitation was lost in the mail… I’m not lamenting her marriage so much. It’s more a feeling that I missed a golden opportunity to be so drunk at her wedding. Slurring and stumbling through an uncomfortable toast. Being vaguely disrespectful, calling her father by his first name. Spilling cheap Merlot on the carpet at some country club I’ll never be invited back to. Having her brother and a host of faceless groomsmen toss me out of the reception. Sitting at home after, letting the sharp yet harmless click of an empty revolver being dry-fired into my midsection over and over lull me into a deep, troubled sleep. These opportunities only come calling a scant few times in life. Carpe diem and all that.“

(der Text wird weiter bearbeitet und ergänzt, und dann im November gepostet in unserer Rubrik „Poetry“ mit dem Ober- oder Untertitel „Poetry In Sound“.)