Vorzeitlich / Archaic / naturgegebene Klangquellen

In einem Kommentar zum Beitrag LIVE ZÄHLT schrieb ich Folgendes:

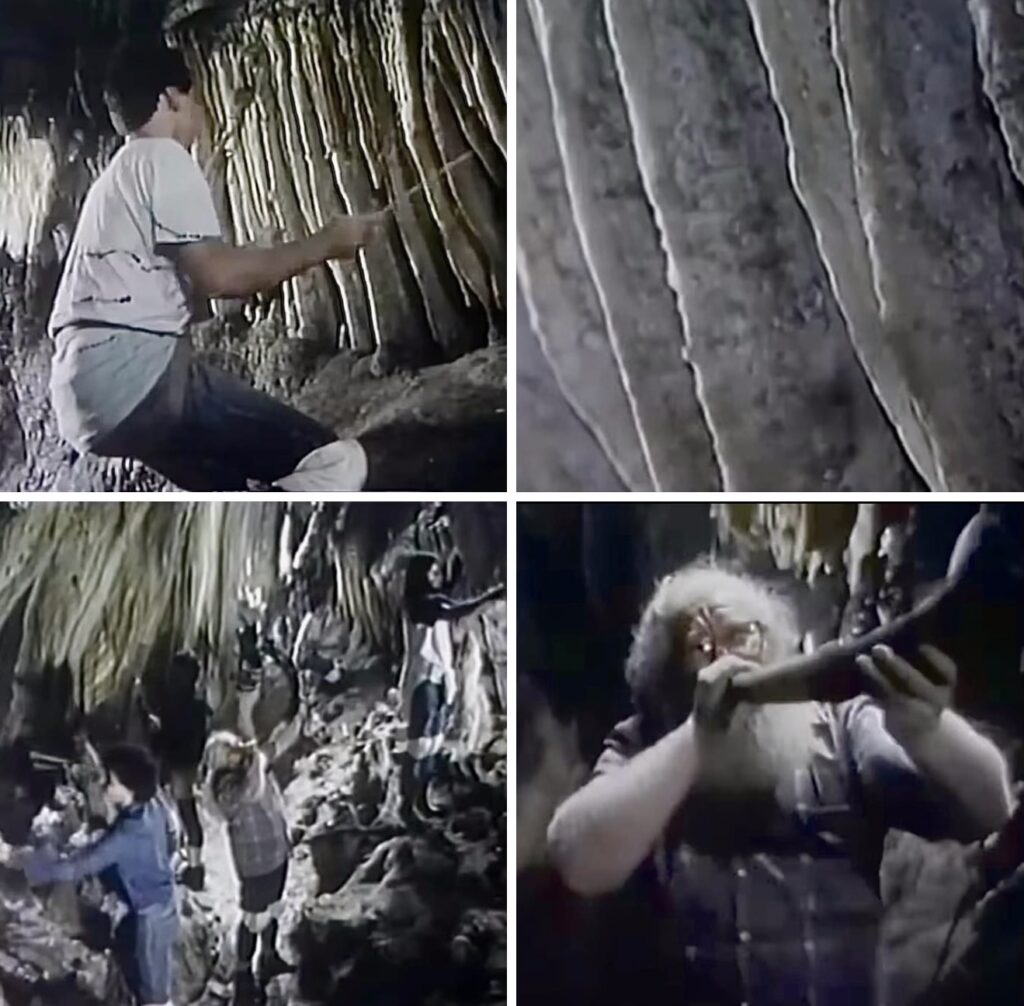

Archeologen haben sich lange gewundert, warum es bezüglich archaischer musikalischer Praxis so wenig Fundstücke gibt. Ja, ein paar zu Flöten präparierte Knochen oder ein paar aus Holz gefertigte Artefakte. Dieses Desiderat brachte einen französischen Akustiker dazu, archaische Resonanzräume näher zu inspizieren, also Höhlen, die als Versammlungsplätze dienten. Ein wichtiger Anhaltspunkt waren für ihn rote Markierungen in Höhlen, die bisher niemand erklären konnte. Seine Prüfung ergab, dass sich an diesen Stellen die besten akustischen Resonanzräume befanden. Aber dann? Aber wie?

Ja, die Instrumente hingen direkt vor seiner Nase. Und koordinierte Schläge darauf erzeug(t)en magische Klänge. Plus die menschliche Stimme, die ja schlicht da war, hatte in so einem Resonanzraum ein erstaunliches Potential (mit Verstärkung und Dubeffekten).

Hermeto Pascoal war vor längerer Zeit auf derselben Spur und nutzte die herunterhängenden Stalaktiten und aufsteigenden Stalakmiten als Klangkörper. Er selbst fügte den Klang eines Naturhorns hinzu.

Televizyon, an older thang still resonating

I

You have to get that INGENIOUS IDEA to take the background sounds of the 80’s of your Turkisch homeland as material to work on with accomplished improvisers and create powerful glittery sound waves from it. Amsterdam based vocalist Sanem Kalfa DID IT joining forces with three mighty creative powerhouses: keyboardist Marta Warelis, drummer Sun Mi Hong, and bassist Ingebrigt Håker Flaten.

Kalfa on the spot caughtbrought-SOMEthing with band members who KNEW-what-to-DO – brilliantly a la moment. Pushing it to unbelievable heights already in their second concert ever (the first one was at WORM, Rotterdam, last year)

And what was this SOMETHING?

The group’s name is the Turkish word for TV, hm. TVs were running in the past (and presently too) permanently flooding people’s living spaces not only with a stream of pixels but also haunting around sounds, soundtracks of people’s everyday life.

It was not that the musicians borrowed from it to noodle-doodle along and around it a bit or mixmax it. No, they wildly enriched the catchy sketchy input of Kalfa to shoot tattering rubber balls into the sky, let jump dancing snakes out of the ground and shoot wildly circling twirling energy salvos into space. This happened in astonishing dense real time creation = improvisation.

It doesn’t went the distortion or circumlocution way. It rather was a heavy concoction emerging from deeper layers‘ of the simple figurations they took off from – a kind of conjuring sound mining. It was sheer astonishing how they drove each other up from/in the moment via different interconnecting axes concerted by Kalfa’s wildly whirling spirit. It was mostly FINDING in the natural phantasy zone, not searching. …The only obstacle were the fixed chairs in the concert hall. It was not only a question of getting carried away but of natural instinct for the next blooming realm.

The concert took place June 29, 2024, at Amsterdam BIMhuis

P.S. : Televizyon came forth from a commission of SPACE IS THE PLACE instigated by a specification of Tim Sprangers “To do something musical with a youth memory”

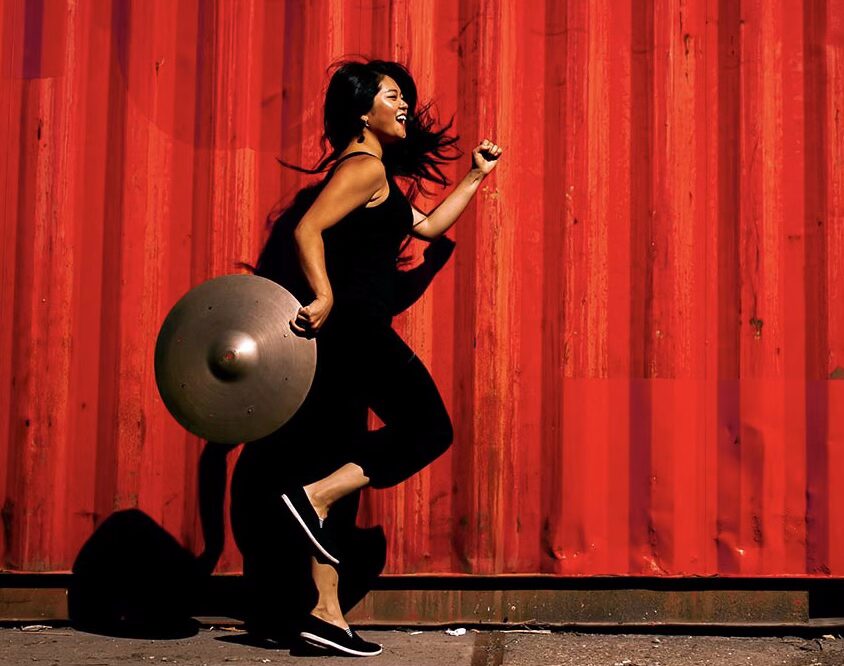

Sun-Mi Hong

Sun-Mi Hong, drummer of Korean origin, is living and working in Amsterdam since more than a decade now. She meanwhile has grown into a central figure in the younger international Amsterdam scene of the 30s and 40s also being in high demand more and more throughout Europe.

Sun-Mi Hong is a person with a strong inner concept and a strong inner force to get into the deep energy and intricacy of the music she is playing. She hits quick, hard and amazingly flexible. Every stroke is 100%, every stroke is SHE. Her hands-on mentality goes together with a stupendous joy of playing and honest openness.

to be continued

November Charts

Europe Jazz Media is a group comprising a greater number of Jazz Magazines, Jazz Websites and critics all across Europe. Monthly each of its members nominates an album deserving extra attention. From these choices the monthly chart is made up. As a founding member of the group I make my choice every month now for more than a decade. I allow myself to present my choices and the complete chart also here. My choice for November 2024 is

|

SUN-MI HONG BIDA ORCHESTRA – Invisible Ropes (Bimhuis Records)

|

Sun-Mi Hong’s Bida Orchestra is a six-piece raw energy unit unleashing exceptional dynamics that convenes ferocious attacks and wild outbursts with classy horn lines as mighty as elegant in utmost thrilling , mutually feeding dialectics. Old contradictions are abolished, overcome and playfully transformed to a higher fully prospering level. With its deeply reaching resilient agility the group creates an increasingly strong unifying thread. It is ferocious, full of unbridled and intelligent joy of playing, reaching into realms of touching beauty. The music designed and lead by exceptional female drummer Sun-Mi Hong fully triggers and unfolds the potentials of her high class international line-up with Mette Rasmussen (as), Alistair Payne (tr), John Dikeman (ts, bas-sax), Jozef Dumoulin (keys) and John Edwards (b). Sun-Mi Hong, a risen star from Amsterdam, is one of the internationally busiest and successful young musicians of the 30s generation. She can a.o. be seen with Bida Orchestra at this year’s Jazzfest Berlin on Thursday, October 31st.

Here’s a YOUTUBE link to the live concert at Amsterdam Bimhuis the album is drawn from. You can find the album on BANDCAMP.

Beirut Birds طيور بيروت

Here is something about and from a contemporary young artist from Beirut, Lebanon. Nour Sokhon is a truly multidisciplinary artist creating dynamic sound spectra of strong undercurrent expressiveness. I saw her several times performing live (at Punkt Festival, Gaudeamus Festival, Hennie Onstage Center) and worked with her (at Schwere Reiter, Munich). For me she is a forceful and imaginative multi-dimensional, multi-layered creator of sound visions permeated by social and political tissues and realities. .

Daily life in urban chaos from relative peaceful times to times of catastrophe and horrible war have their significant sounds people are surrounded by and taken in and lived by, sounds that resonate in their feeling and memories. Human voices in various modes mingle with it and our memory speaks in inner voices and images.

Beirut Birds طيور بيروت, created by multidisciplinary artist Nour Sokhon, is a sonic memory capsule honoring (inter)personal stories of migration, displacement, and the cyclical turbulent circumstances in Lebanon.

Nour Sokhon has undertaken and recorded interviews with diasporas and repatriates to commemorate, share, heal, and envision. These source materials become the album’s core elements that loop, narrate, and return throughout time, with herself responding with both instruments and her voice. Chanting in dialogue with the interviewees, crafting near-mantras, she further congregates these materially-rooted sound-scapes by including field recordings that she gleaned during 2018–2021 in Lebanon and her subsequent move to Berlin.

The pieces contain manipulated sounds from objects that symbolize migration, such as office bells, a luggage wheel, car parts, and bureaucratic paperwork interwoven with and carried by Nour Sokhon’s enriching improvisations on classical piano, electronics, synthesizers, violin, and various percussion instruments.

(text adapted from bandcamp where you can have a listen to the music)

get Bandcamp

Q, der bewundernswerte Allrounder

Quincey Jones hat das Zeitliche gesegnet, und es gibt reichlich Gründe für Lobeshymnen. Q hat Dinge miteinander zu verbinden gewusst und ein bewundernswertes lebenslanges offenes Interesse an den Tag gelegt. Bis in das neunte Jahrzehnt seines rührigen Lebens. Chapeau! Sein respektvolles, einladend schmunzelendes Lächeln galt auch immer jüngeren Generationen wie etwa das folgende Bild von Q mit Vokalistin Sanem Kalfa beim Montreux Festival 2011 zeigt. Sanem gewann damals den Vokalwettbewerb.

Ich will den vielen schönen Nachrufen keinen weiteren hinzufügen, sondern möchte Questlove (von The Roots) das Wort geben.

QUESTLOVE : „Wanted To Reflect On The Hundreds Of Things He Taught Me Throughout The Years. 10 Takeaways Quincy Jones would hammer home throughout the years I’d run into him.

1. The importance of connecting to people (scoring/songwriting/business ventures) your song/message/product HAS to give goosebumps.

2. “You can’t polish doo-doo”——the best singer can’t save a bad song. The most limited singer often make hit songs because limited musicians serve the song & virtuosos tend to let their ego show off too much. The song must resonate

3. Always record your music when your musicians are tired from 10pm-5am you’ll get the best results because Theta brainwaves are subconscious ———always use the “non overthinking” hours to let the magic in

4. My contact list is my most important instrument

5. The importance of sequencing albums & shows——know how to balance your strong material to your more experimental material.

6. Never look down on the generation that’s ahead of you. Never neglect the creations of the generations in your rear view mirror.

7. Study & master all arenas of creativity

8. You are never too old to achieve a new plateau or goal

9. Edit edit edit Less Is More

10. Pay it forward to the next person.

Quincy Delight Jones (1933-2024)

Reel #3

To operate a REEL: zoom in by clicking on the ‘AMSONANZA’ mark when the reel starts. The ‘AMSONANZA’ mark also appears at the end a bit larger. When you click on it, the reel will be repeated.