Uncategorized

Spätzünder

Für mich erstmal eine Überraschung, dass sich Gillian Welch und David Rawlings auf ihren anstehenden Live-Auftritten der Musik von Grateful Dead zuwenden. Ich habe einige Alben dieses Paars, das irgendwo zwischen zeitlosem Folk und neorealistscher Countrymusik eine einsame Klasse darstellt. Was aber Grateful Dead angeht, habe ich mir in ganz jungen Jahren nur ein Album von ihnen zugelegt: „Blues for Allah“. Ich war beeindruckt, aber nicht so, dass ich die Wege dieser Mythenumwobenen weiter verfolgt hätte. Die Neuauflage von „Blues For Allah“ auf Vinyl (Rhino) packte mich dann vor Wochen einmal mehr, ohne sanfte Blicke in den Rückspiegel der Zeit. Also erlaubte ich es mir, zwei Alben der „Grossartigen Toten“ zu besorgen, die mich nach einigem Stöbern besonders anlockten: einmal „Terrapin Station“, ein feines Album, das einen Hauch von „Abbey Road“ in die USA transportiert: Streichinstrumente, grosser Raum, opulente Sphären und feinsinnge Songgespinste! Das alles serviert mit den „deep americana roots“ der Gruppe.

Aber das war nur ein gelungenes Vorspiel für die Wucht und Wirkung, die „Live Dead“ gestern Abend auf mich ausübte. Ich kann mir gut vorstellen, wie dieses ausufernde, wilde, hypnotische Live-Album 1969 auf die Hippie- und Underground-Kultur gewirkt hat, und beneide Lajla, dass sie die Jungs und Mädels einst in San Francisco oder wo auch immer livehaftig erlebt hat: ich staune! Und ich sehe keinen Grund, es nicht an die Seite zu stellen des mir seit 1971 bestens bekannten, immer wieder gehörten, innig geliebten „Live At Fillmore East“ der Allman Brothers. Und mittlerweile kann ich mir gut vorstellen, wie das Duo Gillian / Welche die Melodien und Essenzen der Grateful Dead filtern und verwandeln! Es wird Abende geben, da werde ich das Kerzenlicht anzünden und sehr gerne, je nach Stimmungslage, eines dieser drei Alben aus dem Regal holen. Verdammt gute tiefe Musik. Räucherstäbchentauglich, wenn mir diese kleine „Regression im Dienste des Ichs“ erlaubt wird! (m.e.)

Im Vorübergehen notiert

Der Plan war, heute morgen um 7 Uhr an meinem liebsten einsamen Strand von Lanzarote rumzuliegen und zu schwimmen. Aber die angekündigten Temperaturen spielten nicht mit. Im Süden zu frisch, im Norden zu kalt. Eisberge vor Rügen, really? Die Alternative war, auf der Uwe-Düne in Kampen auf die Nordsee zu schauen mit Ralph Towners „Solstice“ im Walkman. By the way: wer erinnert sich noch an „The Sylt Loneliness Treatment“?! So reinigte ich den Pellett-Ofen, liess meine Mädels ausschlafen, ging Brötchen holen und die kleine Bergrunde. Im März dann!

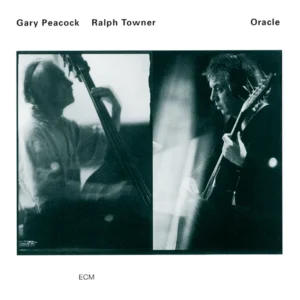

Es ist Steve Tibbetts gewesen, der mir erstmals vor Jahren von Schallplatten erzählte, die in seiner Jugend wochenlang seinen Plattenspieler blockierten: „Dis“ von Jan Garbarek zählte dazu, Jefferson Airplanes „After Bathing at Baxters“, Cans „Tago Mago“. Jetzt, wo ich nur noch wenige Sendungen mache im Jahr, kehrt auch bei mit dieses Ritual bedingungslosen Wieder- und Wiederhören bestimmter Alben zurück. In der letzten Woche hörte ich songut wie nichts anderes als die neue Vinylfassung von „Oracle“ von Gary Peacock und Ralph Towner.

Jens hat schon recht, wenn er das karge Echo der Presselandschaft auf den Tod Towners bemerkt. Aber Der Spiegel betreubt seit Jahrzehnten konservativen Musikjournalismus, „Die Zeit“ hat nie einen würdigen Nachfolge für Konrad Heidkamp präsentiert, und nach dem Verschwinden von Karl Bruckmaiers „Musikseite“ ist auch die SZ im mediokren Zeitgeist angekommen: wenige Ausnahmen bestätigen die Regel, dass jedes neue Beyonce-Album einen Vierspalter verdient und jedes neue Freunschaftsbändchen der Taylor Swift-Gemeinde mehr Aufmerksamkeit erfährt als der Verlust visionärer Musiker jenseits des Mainstreams.

Ich suche noch ein konsensfähiges Konzert als Geburtstagsgeschenk, für das sich die Mädels so begeistern können wie ich. Nicht leicht: In Hamburg, da, wo Elke, Olaf, Norbert und ich Anouar Brahem erlebten im letzten Jahr, tritt 2026 Elvis Costello auf. Das Thema: seine frühen Songs! Retro kann aufregend sein bei diesem Elvis, denn man weiss nie: lässt er es krachen, oder serviert er ein Streichquartett? Aber 110 Euro für einen guten Sitzplatz und die weite Reise bedeuten ein dezentes No. Köln wäre noch okay gewesen.

Es ist ein paar Tage her, da bot ich auf dem Blog den „heiligen Gral“ von Herrn Roedelius zum Verkauf, nun meldete sich ein Interessent aus Passau, der mich auf 150 Euro runterhandeln wollte für meine limitierte „Forster Schatztruhe“ aus den 1970er Jahren. Ich lehnte freundlich ab. So lange Autofahrten ins tiefe Bayern sind schon ein paar Jahre her. Einmal sauste ich mit meinem Toyota nach Garmisch-Patenkirchen, um mir mittels einer Seilbahnfahrt zur Zugspitze die Eustach‘sche Röhre zu öffnen (voller Erfolg!), einmal besuchte ich Manfred Eicher im Hauptquartier, für eine längere Sendung über Tigran Hamasyans ECM-Album „Atmosphères“, einmal trafen sich die „Pioniere“ der kognitiven Verhaltenstherapie für Suchterkrankungen in Furth. i. W. vierzig Jahre später (auf der 8 Stunden Fahrt lief unentwegt Robert Fripps „Music For Quiet Moments“) – drei ganz spezielle „road movies“!

„Zwei Amerikas“ – Joe Boyds Rundbrief

Andrea und ich haben uns auf ein 18-monatiges Abenteuer begeben, um „And the Roots of Rhythm Remain” von Seattle bis Jaipur, von Edinburgh bis Querétaro zu promoten. Menschen und Momente bleiben lebhaft in Erinnerung, aber nur wenige sind so eindrücklich wie die von unserem Besuch in Minneapolis im vergangenen März. Unsere Veranstaltung fand im Cedar Cultural Center statt, einem warmen und einladenden Ort, an dem regelmäßig Künstler auftreten, die aufgrund ihres Aussehens oder ihrer Sprache von ICE-Schlägern von der Straße weggeholt werden könnten. Nach unserem Soundcheck schlenderten wir ein paar Häuser weiter, um in einem familiengeführten Restaurant äthiopisch zu essen. Andrea, die einen Großteil ihrer Jugend in Addis Abeba verbracht hat, erklärte, es sei eines der besten Gerichte gewesen, das sie je gegessen habe.

Am Abend zuvor hatten wir in einem Hmong-Restaurant eine kulinarische Offenbarung nach der anderen erlebt. In den Nachrichten wurde letzte Woche von einer Razzia der ICE in der Hmong-Gemeinde der Twin Cities berichtet. Es fällt schwer, die Brutalität zu verdauen, die wir auf diesen eisigen Straßen sehen, wenn wir uns an die herzliche Geselligkeit in einem wunderbaren Restaurant voller Minnesotaner aller Herkunft erinnern. Wir aßen mit alten Freunden, deren Namen ich aus Vorsicht nicht nennen möchte, da sie derzeit Einwandererfamilien versorgen, die gefährdet sind, wenn sie ihr Zuhause verlassen, um zu arbeiten oder einzukaufen. Ein Freund fungiert auch als Späher, der von der ICE identifizierte Nummernschilder verfolgt und den Widerstand über deren Aufenthaltsort informiert.

Heutzutage scheint es zwei Amerikas zu geben: Bei unseren Veranstaltungen begegnen wir dem Amerika, das Freude an ungewohnter Musik, Essen und Sprache hat und gerne mit Menschen unterschiedlicher kultureller Herkunftzusammenkommt. Diese Menschen legen auch Wert darauf, dass die Fakten stimmen. Auf der anderen Seite der Kluft sehen wir ein Amerika, das Angst vor dem „Anderen” hat und es ablehnt, während es Beweise, die seine Vorurteile nicht stützen, ablehnt und bekämpft. Die Einwohner von Minneapolis mögen vielleicht faktenorientierter sein als die Einwohner anderer amerikanischer Städte, aber die Region scheint Einwanderer und den Reichtum, den sie mitbringen, auf jeden Fall willkommen zu heißen. Vielleicht sind es auch die skandinavischen Wurzeln vieler Menschen, die am Oberlauf des Mississippi leben, die sie gegen Trumps Drohungen, Grönland zu beschlagnahmen, aufbringen. Wie dem auch sei, wir sind ihnen zu großem Dank verpflichtet.

In Großbritannien patrouillieren keine maskierten Bewaffneten auf den Straßen und werfen unschuldige Menschen in Transporter, aber es lohnt sich, an unseren „MAGA-lite“-Moment im Jahr 2013 zu erinnern, als die konservative Innenministerin Teresa May Transporter mit Schildern und Lautsprechern durch Einwandererviertel schickte, um den Menschen zu sagen, sie sollten „nach Hause gehen“ oder „mit Verhaftung rechnen“. 83 Jahre alt zu sein bedeutet, mehr Zeit mit Ärzten des NHS und deren Hilfspersonal zu verbringen, von denen etwa 90 % (jedenfalls in London) eindeutig nicht „angelsächsisch” sind. Ich bin immer wieder bewegt von der Empathie, Effizienz und Fröhlichkeit, mit der ich behandelt werde. Die meisten dieser heldenhaften Gesundheitsfachkräfte haben irgendwann einmal rassistische Beschimpfungen von Menschen mit meiner Hautfarbe erlitten, halten aber dennoch unbeirrt an ihrer Arbeit fest.Die meisten dieser heldenhaften Gesundheitsfachkräfte haben irgendwann einmal rassistische Beschimpfungen von Menschen mit meiner Hautfarbe erlitten, halten aber dennoch unbeirrt an ihrer Aufgabe fest, uns alle gesund zu halten. Ich habe eine Fantasie, in der Nigel Farage und Jacob Rees-Mogg krank werden und mit einem ausschließlich aus Weißen bestehenden Team von Krankenschwestern konfrontiert werden, angeführt von Louise Fletcher in ihrer Rolle als Schwester Ratched aus „Einer flog über das Kuckucksnest“, die eine riesige und ziemlich stumpfe Injektionsnadel schwingt.

Ich lese gerade „The History of White People“ von Nell Irvin Painter. Unter vielen anderen Entdeckungen ist die Tatsache, dass vor dem 16. Jahrhundert die Versklavung von Weißen genauso verbreitet war wie später die Versklavung von Schwarzen. Als diese abscheuliche Institution zu sehr mit Afrikanern in Verbindung gebracht wurde, wurde der Handel mit weißen Männern eingestellt und durch Zwangsrekrutierung, Strafarbeit und Leibeigenschaft ersetzt. Junge weiße Frauen wurden jedoch oft noch als „Beute“ im piratenhaften Sinne des Wortes behandelt.

Eine weitere Enthüllung ist, wie die griechisch-römische Welt „Barbaren” sah und sie als groß und stark, aber auch hässlich, schmutzig und stinkend beschrieb. Diese „Anderen” waren eigentlich Germanen und extrem weiß, sogar ekelerregend weiß, mit fahler Haut, verfilztem strohfarbenem Haar, unverständlicher Sprache und ungehobelten Gewohnheiten. Nachdem Germanen, Angelsachsen und Nordmänner die „europäische Zivilisation“ übernommen hatten, griffen sie diese Beschreibungen, mit denen sie einst selbst beschrieben worden waren, auf und wandten sie auf Afrikaner an. In Trumps Tiraden über Hunde essende Haitianer hören wir Anklänge an Herodot. Allerdings schrieb Herodot über Trumps Vorfahren.

Wenn wir zu angenehmeren Themen übergehen (aber nicht zu weit), finden auch unsere Besuche beim Jaipur Literary Festival in Indien und beim Hay Festival in Mexiko Resonanz. In Jaipur hatten wir die besorgten Artikel (und Berichte von akademischen Freunden) über die Unmöglichkeit, angloamerikanische Studenten dazu zu bringen, ein Buch – irgendein Buch – zu lesen, im Kopf, als wir die eifrigen Scharen junger Inder beobachteten, die zu den Vorträgen und Interviews strömten, Notizen machten, Fragen stellten und Stapel von Büchern kauften. Das Durchschnittsalter des indischen und mexikanischen Publikums dürfte etwa halb so hoch sein wie das ähnlicher Menschenmengen in Großbritannien oder Amerika. Die Welt ist jung und wissbegierig, auch wenn das in unseren eigenen, von den Medien verwirrten Gesellschaften nicht immer offensichtlich ist.

Wenn die politischen Unruhen der 1960er Jahre der Musik dieses Jahrzehnts eine zusätzliche Intensität verliehen haben, könnte dann die derzeitige aufgeheizte Atmosphäre die Leidenschaft in der heutigen Musik noch steigern? Das wird nur die Zeit zeigen, aber Andrea und ich haben in den letzten anderthalb Jahren auf jeden Fall eine Fülle spannender Live-Musik erlebt: Tinariwen beim Green Man Festival, Swamp Dogg und Arooj Aftab bei Big Ears, die Halkiades Band bei Christopher Kings „Why The Mountains Are Black”-Festival in Nordgriechenland, Olivier Stankiewicz, der der Barockoboe rockige Energie verlieh, bemerkenswert bewegende Londoner Tribute an Martin Carthy und The Incredible String Band, der südasiatische klassische Sänger Muslim Shaggan in einem Sikh-Tempel, Dan Penn und Spooner Oldham beim Americana Festival, der südafrikanische Cellist Abel Selaocoe in der Wigmore Hall, Robert Plants Saving Grace in der Festival Hall, Martin Hayes beim Borris Festival, eine Schostakowitsch-Sinfonie bei den London Proms und einige seiner Streichquartette in einer Kirche in Minneapolis, Trio Da Kali im Barbican, Michael Shannon und Jason Nardurcys R.E.M.-Tribute-Band, die mein Werk „Fables of the Reconstruction” aufführte, Martin Fröst, der Coplands Klarinettenkonzert bei den Proms grandios spielte…

Ein Höhepunkt war für mich Emmylou Harris‘ Meisterkonzert in Glasgow während des jüngsten Celtic Connections Festivals. Zu Beginn meiner Zeit als Plattenproduzent fiel mir auf, dass Harmoniegesang viel besser klingt, wenn sich die Stimmen in der Luft vermischen, als wenn jeder Sänger sein eigenes Mikrofon hat. Daher war ich begeistert, als zwei Mitglieder von Emmylous großartiger Band, Phil Madeira und Kevin Key, sich zu ihr in einem weiten Halbkreis um ein einziges Mikrofon stellten, um „Bright Morning Star“ a cappella zu singen; der Klang war tatsächlich so warm und voll, wie ich es mir erhofft hatte.

Als ich in den frühen 60er Jahren zum ersten Mal Bluegrass hörte, gab es immer ein einziges Mikrofon und eine rituelle Choreografie, bei der die Banjo- und Dobro-Spieler ihre Instrumente unbeholfen in Richtung Mikrofon hielten, während sie schicke Soli spielten und sich alle vorbeugten, um den Refrain zu singen. Das klang natürlich großartig. Audio ist nicht der einzige Bereich, in dem altmodisches „weniger” eine Verbesserung gegenüber modernem „mehr” darstellt, aber lassen Sie mich damit nicht anfangen, sonst sitzen wir den ganzen Tag hier.

Bis zum nächsten Mal!

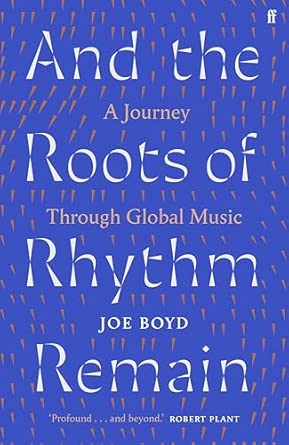

Nachbemerkung von M.E. – Am 12. März ist Joe Boyd in Berlin (siehe comments), und HIER ist ein Gespräch mit ihm, das ferne Jahrzehnte und weit entfernte Räume zum Klingen bringt. Sein Buch ist tatsächlich all die guten Kritiken wert, aber es ist ein Riesenwälzer, das man am besten hin und wieder aus dem Regal holt, um sich in eines seiner Kapitel zu versenken. Joe Boyd gehrört zu den grossen Produzenten unserer Zeit, und vertritt einen spannenden Berufsstand, zu dem mir auf Anhieb Namen einfallen wie Joe Meek (seit ich Jan Reetzes Buch über diesen producer gelesen habe), George Martin, Manfred Eicher, Brian Eno, Daneil Lanois, Rudy Van Gelder, Michael Cuscuna und und und. Die Liste ist lang. Ein besonderes Verdienst von Joe Boyd ist, dass er seine Arbeit und die Musikgeschichte überhaupt auch in zwei tollen Büchern Revue passieren lässt.

„I sing the body acoustic“ (Begegnungen mit der Musik von Ralph Towner)

„Ich habe seine Musik im Laufe etlicher Jahre als zunehmend unverzichtbar empfunden, angefangen von „Solstice“ über die Oregonveröffentlichungen und die Soloplatten. Eine echte Offenbarung war dann „At First Light“, für mich ist da nochmal das ganze Towner-Universum erklungen – und ich habe gespürt, daß das eine Art Vermächtnis sein wird. Ich habe Ralph nie im Konzert erleben können, ich hatte zweimal Karten für ein Solokonzert, eines in Blomberg/Detmold und einmal in Einbeck bei Hannover. Beide Konzerte mussten krankheitshalber abgesagt werden. Selten habe ich es so bedauert, einen Musiker nie live gesehen zu haben. So begleitet mich z.Zt. eine Ralph-Playlist auf meinen Spaziergängen im Schnee, meinem ollen ipod sei Dank, bei „Nimbus“ und „Jamaicastopover“ drücke ich dann auch gern mal die Repeattaste.“ (aus einem Kommentar von Jens)

„Ralph Towners akustisches Gitarrenspiel (classic, 12-string) war bahnbrechend und eine Inspiration – auch für viele Gitarristen. Es wurde – solo und im Oregon-Kreis – nicht nur Musik gemacht – es war, als würden Parallelwelten geschaffen und Naturgötter beschwört. Komischerweise fand ich Klassische Gitarre immer relativ langweilig, aber der Ton, den eine Konzertgitarre erzeugen kann, den finde ich reizvoll. Abends beim Einschlafen zu den Klängen von Towners Twelvestring („Brujo“) hinüberzugleiten ins Traumreich – das bleibt unvergessen.“ (aus einem Kommentar von Jochen)

„My favourite guitarists? Neil Young, wizard – electric. Ralph Towner, wizard – acoustic. And then – Steve Tibbetts. A revelation from the first album onwards. I’ve been returning ever since. Always returning.“ So ähnlich begann ich mein Interview mit Steve über sein Album Life Of, dem Ende 2025 das mich nach wie vor tiefer und tiefer in seinen Bann ziehende Spätwerk Close folgte, viele Jahre später. Den Werken dieser drei Musiker bin ich über Jahrzehnte gefolgt, und hier möchte ich nun ein wenig über meine ersten Hörerlebnisse mit Ralphs Musik erzählen. Sein Auftritt mit Oregon im Sommer 1974 in Münster (im Landesmuseum) gehört zu dem Highlights meiner Konzertbesuche. Im gleichen Sommer sorgten auchb das Gateway Trio mit John Abercrombie, Dave Holland, und Jack deJohnette sowie das Jan Garbarek-Bobo Stenson-Quartett für magische Abende.

Ich bin Jahrgang 1955, und das bedeutete in meinem Falle, dass ich die hohe Zeit der Kinks und Beatles als Teenager voll mitbekam. Teilweise unter der Bettdecke mit Transistorradio, oder ersten Singles. Drei Wochen in den grossen Ferien, morgens gerne dreimal hintereinander, das Sgt. Pepper-Album zu hören, hatte massive Folgen! Bald folgten nich ganz andere Einschläge, wie etwa die ganz frühen Jahre von ECM – als rock- und jazzsozialisiertes Individuum öffnete sich mir auch noch als „greenhorn“ die wilden Klänggebräu des „elektrische Miles“, Soft Machines drittes Album(zu dem ich ein ähnlich obsessvies Verhältnis pflegte wie zu Sgt. Pepper) – und eben die ersten zehn ECM-Langspielplatten. Ähnlich wie Steve Tibbetts (der ja Jahre lang im Plattenladen „Wax Museum“ arbeitete, und die ungkaublichste Musik der entfesselten 1970er Jhre in Minnepolis’ heissesten Vinylshop geliefert bekam), kannte ich von den ersten 300 Platten des Münchner Labels mit der regelmässig wiederkehrenden Zeile „produced by Manfred Eicher“ ungefähr 250. So dicht wie Steve sass ich ja nicht an der Quelle!

Ich glaube, zu meinen ersten zwölf „ECM-Scheiben“ gehörte Ralph Towners „Diary“, ein Soloalbum, das ich immer zu meinen besonderen „Erweckungserlebnissen“ zählen werde. Ich liebte und liebe die Musik so sehr wie das Cover, ich erinnere heute noch, wie Manfred Sack in der ZEIT von seinem „Samtpfotenpiano“ schrieb, als er die Musik dieses klingenden Tagebuches beschrieb, auf dem Towner eben auch mal zu Gong und Klavier griff. Als ich in jenen Jahren darüber hinaus seinem überraschenden akustischen Auftritt auf einem Stück von Weather Reports „I Sing The Body Electric“ lauschte, seinem fast ebenso spartanischen Beimischungen auf Jan Garbareks „Dis“ (unvorstellbar dieses Meisterwerk ohne Windharfe und Ralph), den Oregon-Alben „Distant Hills“ und „Evening Light“, Ralph Towners „Solstice“, war der Pakt besiegelt. Nicht zu vergessen Raph Towners Album „with Glen Moore“ namens „Trios, Solos“, ein erster Schritt, das vertraglich an Vanguard Records gebundene Oregon-Universum zu locken. Ralph Towners 1970er Jahre endeten im Herbst 1979, als live in München und Zürich das nichts weniger als grandiose „Solo Concert“ entstand. Fragen sie mal Wolfgang Muthspiel danach!

Man muss kein Instrument spielen, keine Raketenwissenschaft betreiben, um Ralph Towners Musik zu verfallen – auf ureigene Weise behandelte er in seinem Spiel Unaussprechliches, Parallelwelten, Zwischenzonen: hier wurden tiefe Emotionen und Essenzen ausgelotet, für die es Annäherungen, im Reich der Worte, vielleicht in der modernen Lyrik geben mag, im Bewusstseinsstrom eines Sprachrausches, oder in fantasievoll-pointierter Musikkritik. Hier wie da wäre die Sprache jedoch ein reines Lockmittel, ein Empfehlungsschreiben für die Pforten der Wahrnehmung, die sich letztlich nur öffnen, wenn sich Tonarm und Nadel auf das Vinyl senken, und die Musik beginnt. Let‘s call it deep listening.

Und dann: die späteren Jahre? Der Zauber ging weiter, aber nicht jedes Album hinterliess bei mir gleichermassen tiefe Spuren. So endete für mich die grosse Zeit von Oregon mit dem Tod von Colin Walcott. Weit verzweigen sich die anderen Projekte von und mit Ralph Towner. Die tiefsten Hörerelebnisse hatte und habe ich, wenn Ralph reine Sologitarrenalben aufnahm wie „At First Light“ oder „Anthem“ oder „Timeline“ oder „Ana“. Und auch bei seinen beiden Duo-Arbeiten mit Gary Peacock „Oracle“ von 1994 und, Jahre später, „A Closer View“. Ausgerechnet zwei Tage nach seinem Tod erschien nun „Oracle“ in der „Luminessence“-Vinyl-Serie seines Hauslabels. Umwerfend. Ich hörte es zuletzt jeden Tag einmal vom ersten bis zum letzten Ton, und es packte mich wie damals in den 1970er Jahren („when I was younger, so much younger than today“).

Der Sound: schlicht überragend. Und auf „Oracle“ erfährt man etwas darüber, wie virtuoses Handhaben von Bass und Gitarre keine Sekunde lang in die Falle des Perfektionsmus tappt. Wie zwei Musiker es nie verlernt haben, in ihren Klängen jenen „Geist des Anfängers“ zu praktizieren, der sich dadurch auszeichnet, dass man eben nicht alles zu wissen meint. Und die eigenen Fragen, Ahnungen wie Anmutungen, in jede erdenkliche Tiefe transportiert. Ekstase braucht halt nicht unbedingt, in solchem Einssein von Konzentration und Losgelöstheit, Geschrei und Wildheit. Das Cover selbst, mit den verschwommenen Umrissen der Körper und Instrumente, ein gelungenes Pendant zum „Ungreifbaren“ der Klänge selbst!

Nachtrag zu meinem Album des Jahres 2025

Die französische Fachzeitung „Jazz Magazine“ ist mir bekannt seit der Mitte der 1970er Jahre, ich hatte sie zwei Jahre abonniert. Unvergesslich sind mit die beiden Rezensionen geblieben über „Get Up With It“ von Miles Davis und „Luminessence“ von Keith Jarrett und Jan Garbarek. In der letzteren begeisterte sich der Rezensent über den Ton des Saxofonisten, und verglich ihn, anhand diverser Parameter (Expressivität / Energie etc.), mit etlichen Jazzgranden von Pharoah Sanders bis Sonny Rollins. Der Titel des Werkes war titelgebend für die ECM-Vinylserie „Luminessence“, in der ausgewählte Werke der ECM-Historie in hervorragender Qualität neu aufgelegt werden, zuletzt etwa, und zufällig zwei Tage nach Ralph Towners Tod, sein exquisites Duo-Album „Oracle“ mit Gary Peacock aus dem Jahre 1994. In Kürze folgt meine Besprechung von „Oracle“.

In der ersteren versuchte der Kritiker, den Lesern des Blattes eine Pforte zum „elektrischen Miles“ zu öffnen, die noch immer dem „akustischen Miles“ und seinen zwei alten Quinetten hinterherträumten – am Beispiel der Stücke „He Loved Him Madly“ und „Maiysha“. Nun entdeckte ich auf Steve Tibbetts‘ Homepage einen „link“ im Rahmen der Besprechungen seines neuen Werkes „Close“: „Parlez Vous Francais?“ Hier der Anfang des Gespräches, aus eben jenem „jazz magazine“, der auch eine Erweiterung von Themen darstellt, die in meinem Radio-Portrait vorkamen: Steves enge Verbindung zur Musik von ECM, sowie seine Faszination für den Sarangi-Spieler Sultan Khan. Wer nicht gut unterwegs ist in dieser Sprache, kann es ja leicht mit „Deepl“ übersetzen!

Sur votre nouvel album “Close”, vous mêlez l’acoustique et l’électronique sans qu’on sache très bien ce qui est fait en temps réel ou en post-production. Pouvez-vous nous en dire plus sur le processus d’enregistrement ?

Je pilote des samples avec ma guitare acoustique [Steve Tibbetts, guitare en main devant sa webcam, joue un exemple de la sonorité hybride qu’on entend sur son disque]. Tout est donc fait en direct. J’enregistre depuis 1977, j’ai longtemps été fasciné par les capacités qu’offre le studio. La première fois que j’ai été dans un capable de multi-tracking je me suis dit « c’est ça qu’il me faut ! » Pour moi c’était le son de Tod Rundgren, Mike Oldfield, un rêve que j’avais toujours eu ? Je pensais que si une guitare sonnait bien, mille guitares sonneraient encore mieux ! Mais ça n’est pas toujours vrai. J’ai expérimenté avec ça à une époque mais maintenant c’est une démarche plus solitaire. J’ai aussi remarqué qu’à certains concerts, comme celui du violoniste Leonidas Kavakosque j’ai vu jouer du Chostakovitch en solo, il ne manquait de rien. Il y a bien des années, j’ai aussi été voir le grand joueur de sarangi Sultan Khan, et ça a changé ma façon de voir les choses. Le secret c’est d’essayer de trouver sa sonorité à la guitare avant de l’apporter à quelqu’un pour l’enregistrer.

Quand avez-vous découvert Sultan Khan ?

Mon ami, le tablaïste Marcus Wise, m’avait dit qu’il fallait absolument que j’aille à un de ses concerts, qu’il me donnerait même une place mais qu’il ne fallait surtout pas rater ça. « Marcus, j’ai fait de la musique toute la journée, j’en ai marre, là tout de suite je n’aime plus la musique ». C’était un jour où rien n’avait vraiment fonctionné musicalement, et je n’avais qu’une envie, c’était de rentrer me coucher. Mais il a insisté. J’avais quand même envie de voir les musiciens qui accompagnaient Sultan Khan : le grand joueur de tablas Alla Rakha et son fils Zakir Hussain – un de mes premiers concerts de musique indienne, c’était en 1975 avec Zakir et un flûtiste nommé G.S. Sachdev, un incroyable spectacle. C’était absolument stupéfiant de voir Sultan Khan jouer de cet instrument que je n’avais jamais vu, sa façon de promener son regard à travers la salle en jouant. Il avait facilement 30 ou 40 000 heures de pratique derrière lui, il avait dû commencer à l’âge de six ans et possédait un contrôle total sur le sarangi. Il semblait ne se soucier de rien. Alla Rakha et Zakir Hussain étaient de part et d’autre de lui, marquant des taals [des cycles de pulsations, NDLR] pendant que lui jouait son introduction en solo. J’étais fasciné, tout comme le reste du petit auditorium, rempli de musiciens bouche bée. J’ai été à quelques concerts décisifs comme ça dans ma vie.

Avez-vous le sentiment d’être plus proche que jamais du son de Sultan Khan sur votre nouvel album “Close” ?

Oui. Ou disons que c’est le mieux que je puisse faire. J’ai 71 ans, autant y passer un peu plus de temps sur un disque pour obtenir le résultat qu’on souhaite parce qu’il n’y aura pas tant d’autres occasions que ça. Je ne me projette plus quarante ans dans le futur comme jadis. Donc je suis très satisfait de cet album. Pendant l’enregistrement, mes intentions sont bonnes mais ça ne finit pas toujours bien. Souvent j’en fais trop, il y a trop d’ingrédients, et il faut revenir en arrière. Je compte donc sur Marc Anderson et d’autres pour me dire quand arrêter d’ajouter des choses. C’est aussi quelque chose que m’a appris ECM : certains albums très importants m’ont montré ce qu’on peut accomplir en restant simple. Quand j’ai reçu la lettre de Hans Wendl [qui fut longtemps l’assistant du directeur d’ECM, Manfred Eicher, NDR] m’annonçant qu’ils aimeraient travailler avec moi, je me suis précipité chez mon disquaire et j’ai acheté “Codona III” du trio Collin Walcott, Don Cherry, Nana Vasconcelos, et “Dolmen Music“ de Meredith Monk. C’était tellement génial de passer du temps avec Manfred Eicher et de lui demander comment les sessions de “Dolmen Music” s’étaient déroulées, comment ils avaient obtenu ce son sur le morceau Traveling par exemple. Il m’a dit qu’il avait dû quitter la pièce parce qu’elle était un peu tendue. Je connais Meredith aujourd’hui, nous sommes devenus amis, et elle me l’a confirmé tout en précisant que le résultat n’était pas aussi bon une fois qu’il n’était plus là. Voilà le pouvoir de cette production et de cette simplicité, sans parler du magnifique paysage sonore dont l’ingénieur du son Jan Erik Kongshaug avait le secret.**Im März 2026 tritt Meredith Monk in Berlin auf, wo sie dann auch den „Grossen Kunstpreis Berlin“ erhält. Auch vor dem Hintergrund ihres vielgerühmten aktuellen Werkes „Cellular Songs“ sind das gleich mehrere Gründe, Ingo J. Biermanns Film-Portrait eines Gespräches mit Meredith m März in unserer Seitenkolumne TALK zu veröffentlichen. Ein „Klassiker“ seiner „ECM Conversations“.

In memory of Richard Beirach (1947-2026)

HIER meine Milestones Sendung aus dem Jahre 2019.

Even though Richard Beirach doesn’t know it, I have a special connection to Richie. He has probably influenced me more as a pianist than perhaps anyone else. One night, after a house concert in Sebastopol CA, he invited me into his “dressing room” and we talked for around 1/2 hour. We shared stories about growing up in NYC and going to the clubs etc. Of course, he is a bit older than me, and had had experiences that just weren’t available to me.

We got to talking about other pianists – somehow we got onto the subject of Michel Petrucciani. I told him I had spent an evening hanging out with Michel and some other interesting people (including the late Mel Martin) at a private home. Michel was a fierce coke freak back then and we were at a mutual friend’s house, a bassist who was a total coke fiend. The evening was very intense. A lot of great stories. Michel was a kind of nihilist- he had glass bones disease and he told me he didn’t expect to live past the age of 30 (I think he was around 24 at the time- this was when he was still playing with Charles Lloyd.) That’s another story really…

Richie said he knew Michel and had hung with him. He told me Michel, being so small, liked to walk around at social events and look up women’s dresses. It used to bug Richie and one day he said, “Michel, if you don’t stop that shit I’m going to take you by the head and roll you across the floor like a bowling ball!” He also recommended a Michel duo album with Ron McClure called Cold Blues. I got it and its a very good one.“

– Brian Whistler

Was Andy Partridge mir an einem warmen Sommertag des Jahres 1992 in Swindon erzählte

Zuweilen und sowieso sehr oft stolpert man über eine Erinnerung, die einen kurz aufflackernden Augenblick im endlosen Strom der Zeit wachruft, wie gestern, als ich eine Besprechung in den „Sunday Reviews“ las eines Albums, das meine Regale nie verlassen wird. Es war ein heisser sonniger Tag, als ich bei dem Bandleader von XTC im Wohnzimmer sass, einem Musiker, der uns so wundervolle Alben wie „Mummer“, „Drums and Wires“, „Apple Venus, Vol. 1“ oder „English Settlement“ bescherte – im Laufe ihrer Alben entwickelte sich die Band immer mehr vom New Wave zu barocker, „post-beatles-esker“ Komplexität, die dem sog. „Prog Rock“ weitaus näher stand als der punkigen Wucht ihrer ersten Lebenszeichen.

Vieles drehte sich um ihr neues Opus „Nonsuch“. Aus einem gegenüberliegenden Haus erschall eine Single daraus aus dem Radio, und Andy war froh, dass sie ihren Weg zur BBC gefunden hatte. Als das Gespräch auf Alben kam, die ihn besonders beeindruckt hätten, nicht die üblichen kanonisierten Gipfelwerke der jüngeren Historie, redete er begeistert von „A Walk Across The Rooftops“, dem ersten Album der schottischen Band „The Blue Nile“. Es kommt durchaus öfter vor, dass man den Favoriten hochgeschätzter Künstler nicht wirklich folgen kann, aber in diesem Fall öffnete mit Andy Partridge eine alte grosse knarzende Pforte zu diesen schottischen Aussenseitern, die nie mit einem ihrer Songs die Charts stürmten. Ausser einmal auf Nummer 13 zu landen in den Niederlanden.

Wieder daheim, besorgte ich mir diesen „Spaziergang über die Dachspitzen“, und bald stellte sich jener Kippeffekt des Hörens ein, bei dem aus einer kurzen Phase des Reinfindens pures Beeindrucktsein folgte. Bald auch begeisterte ich mich für das Nachfolgewerk „Hats“, das mir die Plattenfirma als Promo in Form einer guten alten Chromkassette zusandte. Zusammen mit dem dritten Album im Bunde, „Peace At Last“, wurden „The Blue Nile“ wiederkehrende Gäste meiner nächtlichen Radiostunden. Etwas obsessiv war wohl ihr Verhältnis zu den „Linn Drums“, so wie Kate Bush eine Närrin gefressen hatte an der Welt des Fairlight Synthesizers“. Aber, wenngleich man hieran die Spuren einer alten Zeit erkennt, können ihre Alben nach wie vor fesseln, mit ihrer unverschämten Würdigung der kleinen Dinge am Rande unserer Aufmerksamkeit. Mit dem Slow-Motion-Storyteller-Duktus der Gesänge von Paul Buchanan. Mit ihren Mitternachtsstimmungen. Als ich den Mann aus Glasgow dann endlich persönlich traf, in Hamburg, konnte ich es nicht bleibenlassen, ihn nach seiner kurzen Liebesaffäre mit einer meiner aus der Ferne flüchtig, wie auch sonst, angehimmelten Schauspielerinnen ansprach, Rosanna Arquette. In typisch schottischem Understatement spielte er diese Episode seines Lebens herunter, als Rosanna Jahre und Jahre zuvor nach einem Konzert von The Blue Nile seine Gesellschaft suchte und ein paar Schäferstündchen und Liebesnächte folgten.The ways love goes.

Einige Bewunderer von „A Walk Across The Rooftops“ werden in der Besprechung des Albums aufgeführt – Andy Partridge möchte ich hiermit ergänzen. An einer Stelle, die meine volle Zustimmung, erhält, heisst es in Sam Sodomskys „pitchfork“-Text: „For certain listeners, hearing the Blue Nile for the first time activates a part of your brain that exists beyond language and between emotions. It’s the same part that fills in the source of pain between the lines of a Raymond Carver story or maps the road from season’s greetings to profound melancholy in Vince Guaraldi’s Peanuts music. In a Blue Nile song, you sense the lonesome silence beneath the buzz of city life; the unnavigable distance between long-term partners; the acknowledgement that love and loss, life and death, success and failure are forever part of the same cycle.“ Glow-Faktor 10 für „A Walk Across The Rooftops“ und „Hats“! (geschrieben zwischen 10.30 und 11.30 Uhr im Café „Emilia Rue“ in der Rüttenscheider Strasse 239)

Kleiner Nachtrag, ein Tag später: wenn mein einstiger, hochgeschätzter Englischlehrer Dr. Egon Werlich, dessen Einfluss auf mein Leben ich etwa so hoch einschätze wie den von Ray Davies, diesen „Aufsatz“ zu lesen bekommen hätte, dann wäre seine Reaktion wohl so ausgefallen: „Das ist ja alles sehr aufschlussreich und flüssig geschrieben, aber das Thema hast du leicht verfehlt. Was dir Andy Partridge an jenem Sommertag erzählt hat, erfährt der geneigte Leser nicht! Alles in allem eine 3+!“ Tatsächlich weiss ich nicht genau, was mir Andy über „A Walk Across The Rooftops“ mitteilte, alleine seine Begeisterung ist mir im Gedächtnis geblieben. Und da mir die Interviewkassette verloren ging, krame ich nun aus dem Gedächtnis en paar Themen des Interviews aus:

- Andy erzählte mir von dem zweiten XTC Album, und das er mit Barry Andrews gar nicht zurecht kam, (ich mochte Barrys Band Shriekback sehr und sah ihn live 1980 in Weissenohe mit Robert Fripps League of Gentlemen)

- Andy erzählte von seinem Lampenfieber („stage fright“) und seinen Panikattacken, und dass er ab einem gewissen Zeitpunkt nicht mehr live auftrat

- Andy erzählte mir ein bisschen wasüber meinen XTC-Favoriten „Mummer“ (s. Cover), u.a. von dem unvergesslichen Erlebnis, wie ihn eine grosse Welle an der Nordsee umgerissen hatte, was einen der „Mummer“-Songs inspiriert habe (vor Jahren kam eine hervorragend remasterte Vinyl-Version von „Mummer“ auf den Markt)

- Andy erzählte von seiner Zusammenarbeit mit Peter Blegvad und dessen feinem Album „The Naked Shakespeare“ – und gab mir zwei Stücke mit zur freien Verwendung, die er mit Peter im Studio erarbeitet hatte (Unveröffentlichtes)

- Andy erzählte en detail von zwei Songs des brandneuen „Nonsuch“-Albums (das war der Arbeitsauftrag der Pop-Session-Stunde rund um XTC im WDR)

- Andy erzählte mir, dass er nach Album Nr. 2 bei Brian Eno angefragt hatte, und Brian antwortete, sie bräuchten überhaupt keinen producer (ich konnte ja 1992 nicht ahnen, dass Andy sehr bald doch mal in die „Kreise von Brian“ vorstossen würde, als er 1994 mit Harold Budd zusammen die wundersam-ambienten Klanggespinste von „Through The Hill“ veröffentlichte (leider erhielt die Vinyledition als Doppel-LP eine miserable Pressung – ich wurde ein grosser Fan von Steven Wilsons Surround-Versionen diverser XTC-Alben: „Drums and Wires“ etwa, oder „Black Sea“, und die Edition der Duke of Stratosphear-Werke sind absolute Surround-Burner!)

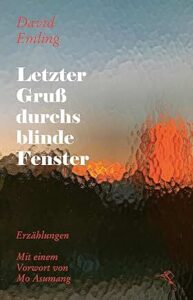

Einzig der gemeinsame Moment würde zählen

Bereits zwei Jahre nach seinem Prosadebüt, der Novelle „Daniels Hang“, legte David Emling im Frühjahr 2024 einen Erzählband vor: „Letzter Gruß durchs blinde Fenster“, erschienen im noch recht jungen Verlag kul-ja! Publishing. Während „Daniels Hang“ das Leben des Protagonisten über einem Zeitraum von sechs bis sieben Jahren begleitet, bis er etwa Mitte Dreißig ist (hier schrieb ich darüber unter dem Titel „Lebensträume“), lotet David Emling in den zwölf Erzählungen seines zweiten Buches seine Fähigkeiten als Autor weiter aus, indem er Perspektiven verschiedener Personen unterschiedlichen Alters einnimmt und seine Figuren vor ihre ganz eigenen Herausforderungen stellt. Das ehrgeizige Lebensziel von Daniel in David Emlings Debüt hatte darin bestanden, Texte über philosophischen Themen zu schreiben und zu veröffentlichen, um anderen damit zu beweisen, dass er über die Welt nachdenken konnte; dieses Ziel verwarf Daniel am Ende der Novelle und setzte als neue Priorität die Familie, die er inzwischen gegründet hatte. Es ist der Grundgedanke vom Wert des Familienlebens oder dem Leben als Paar, also einer Gemeinschaft, der die Erzählungen von David Emlings zweitem Buch wie einen roten Faden durchzieht. Alle Erzählungen handeln von Menschen, die ein „normales Leben“ führen, und, wie es in „Letzter Gruß“ heißt, „genau das und nur das wollten“, auch wenn es natürlich in den Geschichten selbst in der erwünschten Harmonie nicht gelingt, sonst gäbe es ja nichts zu erzählen.

Jeder Text ist auf seine Art fein komponiert, erzeugt beim Lesen sofort einen Sog und große Empathie für die Figuren. Vom Aufbau her folgen die Stories dem klassischen Schema; in einem Gespräch mit mir über Richard Fords Roman „Der Sportreporter“ im Oktober 2017 sagte David Emling, wenn schon das Leben unvorhersehbar sei, solle wenigstens die Erzählstruktur eines Textes verlässlich sein. Nur die Erzählung um ein kleines, ganz besonderes italienisches Restaurant („Kleiner Platz“) durchbricht diese verlässliche Struktur und spiegelt in der Raffinesse ihres Aufbaus einen Gedanken aus dem Text: „noch einmal scheint das Leben nur um sie zu kreisen, alles zu verschwimmen“.

Was die beiden Bücher von David Emling verbindet, ist auch das Nachdenken über das Leben der Eltern. Hier zwei Textstellen aus „Letzter Gruß durchs blinde Fenster“:

„Und hier, in dieser Bude mit Anja, dachte er, dass alles geschehen könnte und Leben eine Freiheit barg, die seine Eltern nie gesucht hatten, ja, von der sie wahrscheinlich nie gewusst hatten, dass es sie geben könnte – und dass diese Frau jene Freiheit mit einer Bestimmtheit verkörperte, die ihn völlig einnahm.“ (S. 46)

„Er könnte eigentlich überall abbiegen, einen neuen Weg einschlagen, ob es so anders wäre, sein Leben. Sich trauen, das Neue zu packen, wie es seine Eltern nie getan haben, bis heute nicht, jeden Tag leben, ohne zu hinterfragen. Er weiß, dass sie zufrieden sind, das ist vielleicht das Schmerzhafteste daran – dass sie nicht nach mehr suchen, oder aber, dass er es nicht schafft, in der Normalität etwas zu finden, das ihn glücklich macht.“ (S. 150)

„Nichts hat einen stärkeren psychischen Einfluss auf ein Kind als das ungelebte Leben seiner Eltern.“ Mit diesem Satz weist C.G. Jung darauf hin, dass es oft die unausgesprochenen Themen, Verhaltensweisen und Lebensmuster der Eltern sind, die das Verhalten ihrer Kinder prägen. David Emling führt in seinen Erzählungen immer wieder Figuren vor, die sich in ihrer Verunsicherung und ihrer Unzufriedenheit auf vermeintlich aufregende Menschen einlassen, dann aber Grenzen ziehen, weil sie irgendwann spüren, dass ihnen das, worauf sie sich eingelassen haben, nicht gut tut. Aus der Erzählung „Progesteron“: „Sie sah ihn an und erkannte etwas.“ (S. 131). Das ist für mich eine der stärksten Stellen des Buches. Wie nebenbei zieht die Frau hier eine endgültige Grenze und befreit sich aus einer toxischen Beziehung. Man lernt jemanden kennen, aber immer dauert es, bis man jemanden einschätzen kann. Vielleicht hat man erst ein seltsames Gefühl, kann es aber für sich nicht begründen. Dann: eine Geste, eine Mimik, ein Satz. Es genügt die Art, wie etwas gesagt wird. Die Erkenntnis, um die es hier geht, ist ein Schock, und es ändert alles.

Letztlich scheinen David Emlings Figuren, wie manche ihrer Eltern, zwar äußerlich in einem „normalen Leben“ anzukommen, aber sie haben andere Lebenskonzepte kennengelernt und für sich abgelehnt. Genau das macht den Unterschied aus. Bemerkenswert ist noch, dass uns David Emling in seinen Erzählungen auf eine sehr rührende Weise Väter vorführt, die wirklich für ihre Kinder da sein wollen. Ein sehr gelungenes, wundervolles Buch!

Fragments of a Snowy Month

Pausenaufsicht, während Schnee liegt, ist nicht vergnügungssteuerpflichtig. Einerseits habe ich Verständnis für die Kinder, für die die weiße Pracht eine große Magie hat. Nicht alle Kolleg*innen haben dieses Verständnis, viele sind ängstlich, dass bei den Schneeballschlachten und dem Rutschspaßen etwas passiert – auch nicht ganz zu unrecht, ich glaube es gab in der letzten Woche drei Gehirnerschütterungen an unserer Schule. Ein Beleg dafür, dass viele Kinder und Jugendliche deutlich über die Stränge schlagen. Insofern freue ich mich über eine Woche Pause (Zeugnisferien) und hoffe, dass der Schnee dann weggeschmolzen ist, auch wenn es derzeit nicht danach aussieht.

Der eisgraue Januarhimmel Niedersachsens ähnelt dem klaren Sternhimmel Afrikas vermutlich wenig, das Album „African Skies“ von Kelan Phil Cohran & Legacy ist aber viel zu gut, um nicht auch im Schneegestöber zu funktionieren. Diese Gebrauchsmusik, ein Soundtrack zu einer Show im Planetarium Chicagos in den frühen 90ern, Klänge zwischen Jazz und Minimal Music eines Sun Ra Gefährten, schafft es verträumt und funky gleichzeitig zu sein.

Deutsches Fernsehen: Die Fortsetzung der Ku’damm Staffel hat uns wieder sehr gut gefallen, bei der zweiten Staffel „Tage, die es nicht gab“ fanden wir die Auflösung enttäuschend, bis dahin gab es aber gute Krimiunterhaltung.

Vor über 20 Jahren musste ich mal Anfang Januar in einer eiskalten Wohnung meine ersten Unterrichtsstunden während eines Praktikums vorbereiten (meine erste Doppelstunde habe ich damals acht Stunden lang geplant), letzte Woche war bei uns zwei Tage lang die Heizung ausgefallen. Auch wenn wir im Wohnzimmer noch mit Holz Heizen konnten wurden die Temperaturen doch unangenehm.

Robert Wyatts „Rock Botton“ war mir unbekannt, bis ich es kurz vor Weihnachten erstand. Wenig überraschend gefallen mir die wunderbar versponnen Klangtexturen sehr, auch diese Musik bringt mich an andere Orte. Und sie ist auch ein Kaninchenbau, der überraschendes zu Tage bringt. Der Name Mongezi Feza klingelte im Kopf, eine Recherche ergab, dass ich über ihn in dem dicken Wälzer von Joe Boyd gelesen haben muss. Eine Radiostunde von Niklas Wandt brachte mich dann zu der Bruderschaft des Atems, bei deren Stück MRA bestimmt kaum jemand still sitzen kann.

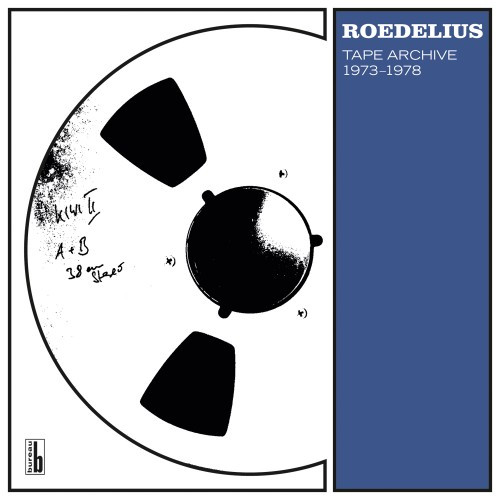

Ich verkaufe den „heiligen Gral“ des Herrn Roedelius

Das ist einer dieser Ausdrücke, die sich in den Musikjournalismus eingeschlichen haben, wenn man von der Höhepunkt eines Lebenswerkes spricht, manchmal ist das „common sense“, manchmal Geheimtip. Ich biete nun den „heiligen Gral“ von Hans Joachim Roedelius an, für 300 Euro. Ich verkaufe dieses „Opus magnum“ (noch so ein beliebter, etwas zu oft verwendeter Ausdruck) nur an Leute, die eine enge Beziehung zur Musik von Roedelius haben. Bei Discogs findet sich derzeit noch ein Exemplar für 200 Euro, ansonsten beläuft sich der Handelswert bis 400, 500 Euro aufwärts.

Zu meinem Verkaufsservice kommt aber etwas hinzu: ich bringe diese Schatzkiste mit drei Lps (und den beiliegenden Cds derselben Musik persönlich vorbei (mit meinem Toyota erreiche ich jeden Ort in Deutschland von NRW aus innerhalb von acht Stunden) incl. einer kostenfreie Übernachtung in einem Gästezimmer und einem gemeinsamen Abendessen (in einem Restaurant Ihrer Wahl, oder zuhause). Als besondere „Dienstleistung“ biete ich einen langen Abend voller Musikgespräche an, die natürlich stets weit über Musik hinausführen können.Bei dieser lang vergriffenenen, numerierten Sonderedition handelt es sich un einen umfassenden Einblick in die Tonskizzen, Miniaturen, Improvisationen von HJR, die an jenem legendären Ort in Forst, Niedersachsen, entstanden sind, als Moebius, Roedelius und Rother zusammenarbeiteten und als Harmonia spannende Alben in die Welt setzten, ganz zu schweigen von frühen Werken von Cluster sowie Cluster & Eno. Natürlich handelt es sich bei diesem Boxset nicht um das beste Album seines Lebens, vielmehr um einen spannenden Einblick in das Entwickeln von Klangideen, welche später im Studio in Weilerswist, aber auch in Forst letzte Gestalt annahmen.

Insofern ist „Tape Archives“, wenngleich kein „heiliger Gral“, kein „opus magnum“, so doch eins rundum interessantes, hervorragend gestaltetes Dokument, das eine ganz eigentümliche Sogkraft entfaltet, und das ich allein deshalb zum Verkauf anbiete, weil ich es damals, nach meinem „open air-Seminar“ über Eno, Cluster und Harmonia vor Ort, also in der Nähe von Forst, von zwei (!) TeilnehmerInnen geschenkt bekam. HIER mein damaliger Einladungstext! Contact: 0157 30765064 / email: micha.engelbrecht@gmx.de (die Kommentarfunktion ist geschlossen, alle Anfragen werden diskret behandelt).

(Michael Engelbrecht)