monthly revelations (may)

album eiko isibashi antigone

film oslo stories: liebe

prose west end jürgen ploog

talk jan and erik on manafon variations

radio playlist in motion

binge high quality tv

archive chick corea piano improv. vol. 1Am westlichen Ende des Abendlandes

Vor einer weiteren Etappe mit dem Kronos Quartet in deren Heimatstadt besuche ich ein paar Museen für zeitgenössische Kunst und kaufe überall (mehr oder weniger) billige CDs. Im Armand Hammer Museum verirre ich mich in eine Ausstellung über Alice Coltrane, „Monumental Eternal“, habe aber nur ganz wenig Zeit, da just in der Stunde meines Ankommens eine Sonder-Performance angesetzt ist, weshalb die Veranstaltungsräume früher geschlossen werden, ich jedoch leider keinen Einlass zur musikalischen Darbietung erlange.

So sehe ich einen Teil der Ausstellung zumindest in flottem Tempo: Zahlreiche Artefakte aus Alice Coltranes Biografie und eine Reihe eigens für diese Räumlichkeiten erarbeiteter Auftragswerke, die mal mehr, mal weniger nachvollziehbar und sinnig daherkommen. Ich notiere mir ein paar Namen mitwirkender Künstlerinnen zur späteren Weitererforschung. Das beste Werk ist allerdings der Tisch am Eingang (kein Urheber genannt), „Please No Food and Drinks inside the Gallery“, in souveräner Klarheit umrahmt von knallig-orangen Wänden.

Zwar kündigt es der Ausstellungstitel nicht an, aber die ein paar Tage später im SF MoMA besuchte Retrospektive mit Werken von Ruth Asawa ist ebenfalls monumental – und zwar monumental umfangreich; man entdeckt Unmengen Unbekanntes. Überaus verlockend sind die vielen tollen Bücher, Bildbände und Biografien im Museumsladen. Aus Kosten- und Gewichtsgründen halte ich mich zurück, gehe direkt weiter in eine ebenfalls umfangreiche Ausstellung mehr oder weniger monumentaler abstrakter Werke, unter anderem von Krasner, Twombly und, immer ein Ereignis, Agnes Martin, mit einer Reihe metergroßer quadratischer Zeichnungen.

Eine Etage tiefer halten sich ungewöhnlich viele Menschen in der Ausstellung von Kunié Sugiura auf. Ich gehe durch, doch begeistert mich ihr Schaffen nicht so sehr, sehe aber eine alte Frau dort umhergehen, die, so denke ich mir, erstaunliche Ähnlichkeit mit der Künstlerin auf den verschiedenen Fotografien in der Ausstellung hat. Sie lässt sich dann auch mit einer anderen Besucherin vor einem der Werke fotografieren, und ich stelle fest, dass das gerade die Eröffnung ist, und die Frau natürlich die bald 83 Jahre alte Künstlerin selbst.

Ausstellungen mit frühen Fotografien von Paul McCartney und Filmen von Isaac Julian im deYoung schaffe ich leider nicht mehr, fahre aber immerhin auf den Observation Tower hinauf. Und filme stattdessen verschiedene supertotale Stadtpanoramen von verschiedenen der zahlreichen Hügel, die ich an anderen Tagen angestrengt mit schweren Equipment-Rucksack auf und runter laufe.

Was andernorts offenbar noch kaum jemandem bekannt ist: Das komplette Taxibusiness wurde mittlerweile von Waymo übernommen, die überall der Stadt fahrerlose automatische Autos einsetzen. Auf den ersten Blick dachte ich: „Ah, ein Gugl-Street-Auto“, aber dann waren es auf einmal so unglaublich viele davon, dass ich erkenne: Die fahren alle mit leerem Fahrersitz und Kameras links, rechts, vorne, hinten, oben und unten durch die Straßen und folgen den Verkehrsregeln (Stoppschilder an jeder Straßenecke) zuverlässiger als alle menschlich geführten Autos. So gesehen eine tolle Sache, denn das hält die Menschen dazu an, ebenfalls vorsichtiger zu fahren und die Verkehrsregeln in Ehren zu halten.

Passengers, revisited!

Am Record Store Day tauchte ein Vinyl-Remaster der „Original Soundtracks 1“ der Passengers auf, und es ist ein fantastisch klingendes Remaster. Nach Mark Smotroffs Eloge war ich so heiss auf das Doppel-Vinyl, dass ich es ziemlich teuer bezahlte. Aber heute lief es schon zweimal hintereinander – tatsächlich hat es nie so gut geklungen, es ist hochexperimentell und himmelweit. Voller Risse, Schnitte, Kontraste, Kühnheiten – und heartbreaker! Eno in the science-fiction wilderness! Dass ich selbst für Bono hier nur Lob übrig habe, bedeutet entweder falsche Drogen, oder, dass es sich um eine scheisswundervolle Scheibe handelt. Angeblich hat es HHV bald wieder für 48.90 Euro auf Lager. Es wäre noch viel zu diese Werk zu sagen. Ich dachte, ich würde es nach einer gefühlten Ewigkeit des letzten Hörens „ganz gut“ finden, es hat mich nahezu umgehauen! Hinterher musste ich erstmal runtergekommen, und fand dazu den idealen Song, der die Energie der Passengers auf seine Weise abholt und in einen Tanz verwandelt. Rhythm of the Heat, der Auftakt von Peter Gabriels bestem Album.

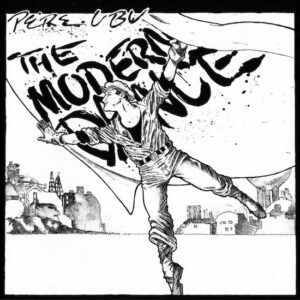

In memory of David Thomas, and if you listen to one his records, take this one!

Pere Ubu’s “avant garage” – a turbulent mix of punk, garage, art rock, jazz, experimental noise and influences ranging from MC5 to Sun Ra – ushered in a no wave/postpunk sound and inspired bands including Joy Division, Gang of Four, Sonic Youth, REM and Pixies. Other fans ranged from Rebus writer Ian Rankin to Beach Boys lyricist Van Dyke Parks, who once introduced Thomas to Brian Wilson with the words: “Meet the other genius”.das 27. Mana Musik Rätsel

Als ich gestern von meiner Reise in die alte Heimat zurückkehrte (ich empfehle jedem mit gutem Sinn für Humor und enttraunatisierte Kindheitsstories den gestrigen Post in Ruhe zu hören („Zurli erinnert sich“)), entdeckte ich zweimal die gleiche CD unter meinen Neuheiten, das famose spoken word Album von Amelia Barrett und Bryan Ferry. Wer als erster die die folgenden Fragen richtig beantwortet, erhält per Post eben diese, sowie eine ECM-Cd. Die Antworten ausschliesslich an meine alte Mailadresse: micha.engelbrecht@gmx.de Und nun geht es los. Gefragt wird nach fünf Albentiteln (bitte nur mitmachen, wenn daheim auch das Medium CD gehört wird)… der Gewinner wird hier im Text bekanntgegeben, natürlich nur mit Namen! Musik aus allen fümf Alben lief, mitunter öfter, in den Klanghorizonten über die Jahre, und alle genannten Platten finde immer noch sehr, sehr gut. Lifers! Wobei das von Roxy seine high rotation doch ein paar Jahrzehnte hinter sich hat…

Wie heisst das einzige ECM-Album, bei dem der Pianist Herbie Hancock mitwirkte?

Wie lautet der Titell des Albums, bei dem Brian Eno zwei Songs der Beatles und Kinks singt?

Wie heisst das erste Album, bei dem Bryan Ferry ohne seinen „Paradiesvogel“ dastand?

Wie lautet der Titel des einzigen Albums, bei dem Eberhard Weber und Mal Waldron dabei waren?

Wie lautet das Album, bei dem Steve Tibbetts ein Stück von Led Zeppelin covert?And the winner is…. Lorenz Edelmann…. hier die richtigen Antworten:

1. The Jewel in the Lotus

2. 801 live

3. Stranded

4. The Call

5. Big Map IdeaDie gute alte Singerhoffstraße – Zurli erinnert sich

Zurlis Erinnerungen beim Abwandern unseres alten Schulweges

Es gibt diverse Wege, sich auf die Suche nach der verlorenen Zeit zu begeben. Aber besonders lohnend ist es, einmal oder mehrmals die alten Wege, die nie ausgetreten sind, neu zu gehen. Mein Glückfall, dass mein alter Kamerad Zurli dabei war. The last time I walked this way was in 1965. unser alter Schulweg in Dortmund-Hombruch. Mein Mitschnitt ist, ungefiltert, knappe zwanzig Minuten lang – und selbst beim dritten Anhören musste ich herzhaft lachen. Und der trockene Humor von Zurli ist ansteckend. (Nächster „Einakter“ im Sommer: „Remembering Weissdornweg in the 60‘s“)

Hawkwind‘s magic first album

Deshalb liebe ich auch das erste Hawkwind-Album. Es ist sowohl von der Unschuld der Psychedelia als auch von der (Vor-)Erfahrung des Punk geprägt. Unglaublicherweise neigen viele Hardcore-„Hawkfans“ dazu, es zugunsten der späteren Alben auf Charisma (!) abzutun, und das ist eine Schande. Denn Hawkwinds gleichnamiges Debüt war anders als alles andere, was sie jemals wieder aufnehmen würden. Zunächst einmal war der Gesamtsound so organisch und dünn wie ein filigraner Moosschleier, während er Stimmungen vermittelte, die so verwirrend nach dem Jenseits griffen und dabei genauso scheiterten wie das primitive Coverbild.(from Julian Cope‘s Head Heritage)

Allison Flood und Michael empfehlen Kriminalromane (1)

„Meine letzte Lektüre in diesem Monat ist ein guter alter Polizeiroman: When Shadows Fall des ehemaligen Metropolitan Police Detective Neil Lancaster, der neueste Fall von DS Max Craigie. Ich habe die vorherigen Romane der Craigie-Reihe nicht gelesen, war aber von Lancasters Prämisse angetan: am Fuße eines schottischen Berges wird die Leiche einer Frau gefunden, die sechste, die innerhalb eines Jahres auf diese Weise ums Leben kam. Alle waren erfahrene Bergsteiger; alle waren allein; alle waren blond. „Alle waren gut vorbereitet, das Wetter war gut, die Wege fest und es gab keine Anzeichen für dummes Verhalten… Was, wenn jemand es auf einsame Bergsteigerinnen abgesehen hat und sie von den Klippen stößt?“ Mir gefiel das Netz des Bösen und der Korruption, das hinter diesen Todesfällen steckt und das Craigie und sein Team bei ihren Ermittlungen langsam aufdecken, und ich war angenehm erschrocken über die Situationen, die Lancaster den Bergsteigern schilderte, als sie ihr Ende fanden. Mittendrin in eine Serie einzusteigen, ist jedoch nie eine brillante Idee, und die Geheimnisse von Craigies Privatleben waren für mich infolgedessen weniger faszinierend. Daher empfehle ich den Autor, schlage aber vor, dass diejenigen, die die Sammlung noch nicht kennen, sich mir anschließen und mit dem ersten Craigie-Roman, Dead Man’s Grave, beginnen, der 2021 auf der Longlist für den McIlvanney-Preis für das schottische Krimi-Buch des Jahres stand.“

Allison hat natürlich Recht. Und rein zufällig lese ich gerade diesen vielgerühmten ersten Roman der Reihe um Detective Sargent Max Craigie. Es ist der erste Thriller, der mich fesselt, seitdem ich Liz Moores „Der Gott des Waldes“ vor Monaten verschlungen habe. Ich gehe soweit, schon jetzt, nach 159 Seiten, Neil Lancaster als Entdeckung zu bezeichnen. Eine ungewöhnliche Handlung, hoher Realismus, gute Humor, zwei sympathische Protagonisten (Janie Calder ist die Ermittlerin an der Seite von Max), und „Highland Noir“: all das sorgt für einen hohen „flowfaktor“! Bisher wurde auch der zweite Teil der Serie ins Deutsche übersetzt. In diesem Jahr werden übrigens zwei Romane meines Lieblingskriminalschriftstellers James Lee Burke in deutscher Übersetzung erscheinen. Einmal „Clete“, und dann der „standalone“ „Im Süden“, eine Geschichten aus der Zeit des Amerikanischen Bürgerkrieges, der im letzten Jahr den „Edgar“ als bester Thriller des Jahres gewann. Neil Lancaster verkürzt die Wartezeit auf den Altmeister aufs Feinste!Re-packaged Passengers

(highly recommended for my analog friends: we will soon meet in Hamburg, guys!)

If you are like me and haven’t thought about Passengers and Original Soundtracks 1 in a long time, now might be the time to revisit this fine “new” album. Hearing it on vinyl for the first time, the music opens up in a fresh manner, compared to the relatively sterile sound of the original 1995-era CD. I love having this music spread out across four album sides, which allows us to better appreciate the song sequencing without it all getting lost as a mushy, hour-long digital playlist. Stopping to flip each side gave my brain a chance to take it all in, and better appreciate what I just heard.

Sonics-wise, there is no contest compared to the CD — the new vinyl edition of Original Soundtracks 1 sounds bold, round, and punchy, with loads of low-end, subsonic-style dance-beat vibes percolating beneath without sounding tubby-thumpy flaccid. Yet it’s not all boombox-car low-end here, as there is lots of nice midrange and high-end sparkle.

In closing, I’ll summarize that this new 180g 2LP vinyl reissue is like hearing Passengers and their Original Soundtracks 1 anew for the first time. If you love Brian Eno and U2’s work together, you probably need this one in your vinyl collection, ASAP.

„binge me sweet, baby, clear my mind“ – eine kleine auflistung hervorragender serien der letzten zeit

Nun, das zweite oder dritte goldene Zeitalter der TV-Serien ist aus und vorbei. Aber, Freunde von Twin Peaks und (um mal hundert Jahre zurückzugehen) „Mit Schirm, Charme, und Melone“, kein Grund, nostalgisch zu werden! Wer unverzagt auf Suche geht, mit gnadenlosen 10-Minuten-Tests von Pilotfolgen, findet Juwelen im Dreck, „deep stuff“ sogar auf Streaming-Diensten, die ihre nächsten Serienstoffe vorzugsweise an Kundenalgorythmen abklären. Und so haben sich bei mir diese folgenden Serien als Bereicherungen der Abende, des Geistes, und der Seele herausgeschält, als „food for thought and thrill“. Und mitunter auch eine gehörige Herausforderung.

Fairerweise möchte ich hinzufügen, dass es für den vollen „impact“ von „The Newsreader“, „The Last Of Us“ (Vorsicht, Zombies!), und „The White Lotus“ unerlässlich ist, die insgesamt vier vorausgehenden Staffeln zu sehen. Das ist allerdings keine Anstrengung, sondern das reine dunkle Vergnügen! Die auf Arte Mediathek laufende Geschichte über einen australischen Nachrichtensender Mitte der Achtziger Jahre ist wohl immer noch ein Geheimtip hierzulande – don‘t miss it!

“Spuren“

„Families Like Ours“

„Black Mirror 7“

„The Last Of Us 2“

„The White Lotus 3“

„Toxic Town“

„Adolescence“

„The Newsreader 2“Ich war ja schon fast wieder zum Kinogeher geworden, und, in kürzester Zeit, beeindruckt bis sehr beeindruckt von den Zeitreisen in die Musik meiner frühen und sehr frühen Jahre, und den kleinen Erforschungen dessen, was im Laufe der Jahre vom jüngeren Ich erhalten bleibt, was auf der Strecke. Dafür waren „Köln 75“, „Like A Complete Unknown“, und „Coastal“ idealer Stoff. Chapeau!

Zum Ende noch ein Kinofilm auf Prime oder Netflix, den ich hier mal in der Kategorie „my guilty pleasure“ empfehle, besonders für Freunde des „shark movie“-Genres. „Something In The Water“. Ein Film, der weitgehend verrissen wird, aber von mir blutige vier Sterne erhält. Im Nachgang stromerte ich bei „rottentomatoes“ herum, und fand dann doch etwas Zuspruch von der Zeitung meines Vertrauens: „Audiences hoping for lashings of graphic violence may be disappointed that not all of these problems involve gallons of blood – this is a relatively gore-free thriller – instead, it’s all aboard and anchors aweigh for some larky tension between likable characters who find themselves plunged into a nightmare scenario.“ Ein Grund mehr, langsam mal in eine Popcorn-Maschine zu investieren!