Uncategorized

Der Genozid

„Seit mehr als einem Jahr erleben wir ein unfassbares Ausmaß an Tod und Zerstörung im von Israel besetzten Gazastreifen. In Reaktion auf Kriegsverbrechen der Hamas und anderer bewaffneter palästinensischer Gruppen bei ihrem Angriff auf Israel am 7. Oktober 2023 hat die israelische Armee eine brutale Militäroffensive begonnen. Israel hat zehntausende Menschen getötet, ganze Familien ausgelöscht, Wohnviertel dem Erdboden gleichgemacht und lebenswichtige Infrastruktur zerstört. 1,9 Millionen Palästinenser*innen, mehr als 90 Prozent der Bevölkerung des Gazastreifens, wurden bisher vertrieben – oft mehrfach. Diese menschengemachte humanitäre Katastrophe ist beispiellos.“

(Amnesty International. Weitere Informationen HIER!)

„Lofoten, Lotus, Luminal“

„If this month‘s „horizons of sound“ at Deutschlandfunk, May 29, 9.05 p.m., is brimming with life, with the usual suspects from Eno to ECM, the „Klanghorizonte“ at the end of July will bring you – incl. sound, vision & interviews – some voices of Clay Pipe Music, label owner Frances Castle and electronic wizzard Cate Anne Brooks, and much more, for example the forthcoming solo album „Solace Of The Mind“ by Amina Claudine Myers.

Nach einem aufregenden Wochenende mit dem BVB erhielt ich von unserem Ratefuchs Lorenz aus Leichfelden-Echterdingen folgende Mail:

Hallo Micha, dein Päckchen ist wohlbehalten angekommen mit den 3 tollen CDs. Jede auf ihre Art klasse.Loose Talk erinnert mich an Laurie Anderson und auch Brian Eno (the Drop Phase). Wunderbare Geschichten, die sie erzählt. Joe Hendersons „Multiple“ hat absolut tolle Grooves und Überraschendes, wie den Gesang im ersten Stück oder auch immer wieder seltsame Keyboard sounds. Danke für diese super Entdeckung. Wie Joe Lovano und das Trio zusammen sind, auseinander driften und sich dann irgendwo anders wieder finden ist schon fast wie ein Jazzhörspiel. Großes Ohrenkino. Ja, und der Kaufbefehl für die Zwillingsalben mit Brian Eno stößt auf offene Ohren … Wenn nicht sogar noch Robert Foster dazu kommt, denn die Besprechung aus MOJO (5 stars) liest sich sehr interessant. Viele Grüße und lieben Dank! (und viel Spaß in der Champions League) Lorenz

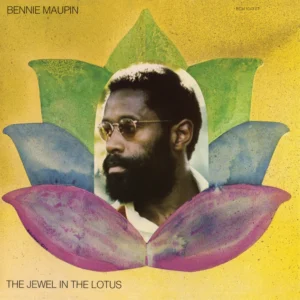

Mittlerweile verweile ich bei den Moderationen der Klanghorizonte für den 29. Juli. Die Stunde beginnt und endet mit grossartiger „Ambient Music“ aus Japan und England von Hiroshi Yoshimura sowie Brian Eno & Beatie Wolfe. Als „Album der Ausgabe“ wird „Luminal“ von Wolfe und Eno vorgestellt. Um mich selbst zu zitieren: „In regards to „Luminal“, surely one the most beautiful, haunting and seductive song albums of 2025, there is only one reason I don‘t come up with the minor quibble that Brian Eno isn‘t doing the lead vocals, and that is the voice of Beatie Wolfe! Und lässt man Musiikhistorie rückwärts laufen, hat folgende Ankündigung doch ihren Reiz: Im zeitlichen Zentrum gibt es einen Song aus dem spoken-word Album von Amelia Barratt und Bryan Ferry, flankiert von zwei ECM-Alben, „New Vienna“ von Keith Jarrett (ein weiteres Dokument seiner letzten Europareise von 2016), und „The Jewel In The Lotus“ (ein Klassiker des sog. „spirituellen“ oder „Fusion Jazz“ von 1974).

Am 27. Juni erscheint das Album aus dem Hause Clay Pipe Music, das mich gestern erreicht hat, und das ich in den Klanghorizonten Ende Juli ganz sicher vorstellen werde, „Lofoten“ von Cate Anne Brooks. Das Hauptquartier dieses feinen „independant labels“ aus London vermeldet folgendes dazu (der Kaufbefehl wird beizeiten ausgeprochen und das Teil könnte sich in der heimischen Albensammlung finben neben „Flora“ und „Lateral“):There are imagined landscapes we all carry within us—dreamed, half-remembered, or just beyond reach. Lofoten, the new album by Cate Francesca Brooks on Clay Pipe Music, is a musical reflection on one such place. Located above the Arctic Circle, Norway’s Lofoten Islands are known for their dramatic peaks, open seascapes, and distinctive red fishing cabins dotting the shoreline. Though Brooks has never visited this remote northern region, it became an unexpected source of inspiration.

The project began when Cate listened to a narrated „sleep story“ set in the islands. Intrigued, she researched the region and found herself drawn to its stark beauty. „I fell in love with creating an impression of somewhere I would probably never visit, but felt a real affinity with,“ she explains.

This ambitious album translates that connection into sound. Through carefully crafted electronics, melodic themes, richly layered textures and big production, Brooks captures the essence of Lofoten—its icy light, vast horizons, and profound quiet.

„The other thing that happened around the same time was the first lockdown here in the UK. I had taken the opportunity of having some extra time to learn a new (to me) method of synthesis; that of the Synclavier, which uses one aluminium wheel and an array of buttons to control every parameter of the sound.

„I took to it with intrigue and before I knew it, I had built up hundreds of original sounds, many of which were perfect for the textures I could hear in my head for Lofoten. So that (along with a Prophet synth and a TR-808) became the sound world.“

Lofoten stands as an evocative testament to how music can transport us to distant places, transforming geographical limitations into imagined creative possibilities.

canariasjazz.com

My song of the morning: „The Zoological Gardens“ by The Dubliners. Als ich vor 5 Jahren auf El Hierro landete, gab mir Uli Koch (former manafonisto) den Tipp mit: dort gibt es alljährlich im Sommer ein internationales Jazzfestival. Inzwischen gibt es auf allen 8 kanarischen Inseln durchaus vorzeigbare Jazzfestivals.

Bist du auf List

Mach dir ne List

Hast du’s mit Inselgrammar

Hier ein paar wordshämmer

die List

listen

listig

listvoll

Listo Lista Listu

mi ListeDEE DEE Bridgewater Quartet 4.7.25 Teneriffa(US)

Alain Perez y la Orchestra 4.7.25 Gran Canaria(Kuba)

Gonzalo Rubalcaba with Matt Brewer y Eric Harland Gran Canaria(Kuba)

Take 6 y Orchestra Philharmonica(US)

Aimée Nuviola (Kuba)

Vijay Iver Trio (US)

Melissa Aldana Quartet (Chile)

Lakecia Benjamin (US)

Kennedy Administration (US)

Rita Payes (Spain)

Ariel Bringuez Quintet (Kuba)

Kristof Kobylinski (Polen)

Matteo Mancuso (Italien) (da geh ich hin!)

Espen Berg Trio meets Villu Veski (Scandinavia)

Giovane Orchestra( Sizilien)

The Bamboos (Australien)

Arin Keshishi Quintet (Armenien/Iran)

Ellister van der Molen (NL)

Zuco103 (NL)

Dahoud Salim Quintett (NL)

und viele Jazzmusiker von den Kanaren…Ich werde mir Esther Ovejero am 4.7. auf La Graciosa anhören.

VAMOS!

Der letzte Spieltag

Aus unserem „Europasong“ versuche ich immer noch ein Haiku zu machen – schwierig! Es ist wohl eine alte Tradition, in der Hafenkneipe meines Vertrauens alte BBC-Kassetten aufzulegen (an Tagen, an denen der BVB Grosses und Kleines zu feiern hat), in denen der grandiose Bandleader von The Clash eigene Lieblingsplatten erzählend und auflegend Revue passieren lässt, und dann ziehen die Stimmen von Nina Simone, Bob Dylan, und Jacques Brel seltsam zeitlos ihre Kreise, wie heute, als der der BVB nach einer lange Zeit grottigen Saison in einem furiosen Endspurt unter dem neuen Publkumsliebling Niko Kovac noch auf den lukrativen Platz 4 sprang. Wo läuft denn gerade Rod Stewarts „Hymne“? Eine ausgelassene Stimmung herrschte zwischen Kreuz- und Hafenviertel nach 17.30 Uhr, und so tauchte ich im „Sub Rosa“ mitten in eine Geprächsrunde ein, in der Ronald Rengs wunderbares Fussballbuch „Spieltage“ verhandelt wurde: Fussball und gute Musik, das passt hier zusammen, Sprünge über Generationen, glücklich erschöpfte Gesichter. (m.e.)„Thursday Afternoon in Paris“

A dream story with an album you’ve never heard of. Once again you are there, in your beloved little park called „Le Jardin du Luxembourg“, not far away from that old time jazz club, „Le Chat Noir“, Robert Wyatt once sang about, a smoky club with wooden walls that is long gone, with all its long stories, told and told again. Or never told. You still have a Sony walkman from the past that works fine, except for some stutter in winter. You put in that cassette a friend gave you as a gift and a sweet reminder of hot love and the best galettes in town. You never knew about this album to exist. Pretend, it is 1998. For reasons hard to explain you keep playing this one track again and again on a warm afternoon in Paris. A sentimental journey, and this piece HERE calls you by your name.Hawk Dreams

Zehn Jahre ist das Label International Anthem nun alt, es hat uns einige wunderbare Werke beschert, und nun bringt auch Blue Note ein Album heraus, das mit Carlo Niño, einen Perkussionisten und Geräuschemacher im Rahmen des „Openness Trio“ präsentiert, der wie wenige andere für die Welt von International Anthem steht. Selbst das Cover könnte von IAR sein. Aber lauschen wir einfach mal diesem langen Stück, um herauszufinden, ob wir Andy Cowan zustimmen, wenn er in Mojo schreibt: „… And while there are traces of Jon Hassell, Pat Metheny and Sun Ra, the next-level meditiations of „Openness Trio“ navigate unexplored frontiers, where inner and outer space is the place.“

Sollte das Album nur annähernd Andys Worten gerecht werden – auf Strecke – wäre es eine Idee, die Klanghorizonte Ende Juli damit enden zu lassen, und sie mit „Chicago Waves“ zu beginnen, einer International Anthem-Produktion von 2020, dunklen Zeiten also (die Zeiten sind dunkel geblieben, aber Covid sorgte damals noch mal für einen besonderen Schrecken), dem Mitschnitt eines vielgerühmten Duo-Auftritts von Miguel Atwood-Ferguson und Carlos Niño, der in Kürze als LP neu aufgelegt wird.

Die Stunde der wahren Empfindung

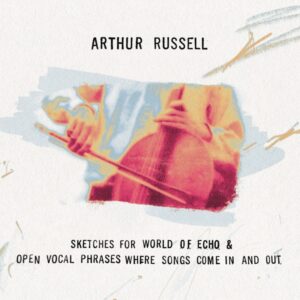

Es ist kein Problem, hier mal einen Titel von Peter Handke zu klauen. Wir haben viel zu wenig über Arthur Russell gesprochen. Rasch werden da die einschlägigen Fakten abgegriffen, die unterschlage ich einfach, oder lass sie nebenbei einfliessen. Sein Nachlass wird akribisch aufbereitet von Audika Records, und die Musik dieses „outsiders“ teilt die Lager. A love it or leave it (or love it sometimes)-affair. „Worlds Of Echo“, „Another Thought“ und das frühe Opus „Instrumentals“ sind meine gern genannten Favoriten. Sein Werk so facettenreich – als allererstes springt sein seltsam verletzlicher, weltoffener wie intimer Gesang vors innere Ohr, umgeben von Echos und seltsam brüchigen Celloklängen. Zuletzt erschienen, neu gebündelt, diese zwei Liveaufnahmen aus den Jahren 1984 und 1985, ein verwegenes Doppelalbum. Wie bei Thelonious Monk kommen immer wieder die gleiche Titel ins Spiel, und wie bei Monk ist das ganz egal und sowiesoso immer anders. Beth Gibbons, die Tindersticks und Lambchop lassen Arthur gerne stückweise vor ihren Konzerten laufen, ich hörte ohn da stets heraus. Er hat also ein paar verdammt gute Fürsprecher. Seit ich irgendwann einen Text von David Toop im Wire über Arthur Russell las, lang ist es her, komme ich auf ihn zurück, wieder und wieder, und nicht aus Chronistenpflicht. Manche bleiben dabei, dass da einer hilflos im Nebel stochere, ich spreche lieber von der Stunde der wahren Empfindung. Und dieses Doppelalbum aus alter Zeit ist zweierlei: eine ideale Einführung in seine Musik, und Stoff zum Versinken. Nicht nur die zwei Alben von Beatie und Brian bieten „space music“ und „dream music“. Er würde auch, anders als ich hier, keine grosse Welle machen, und einfach aus dem Stegreif „Go Swimming“ vortragen, mit einem Cello, das die halbe Welt für beschädigt hält. It‘s a miracle! A dream from the dance floor!

Jonas Engelmann: Gesellschaftstanz

Sein Interesse gilt den Außenseitern des Musikgeschäfts. Denen widmet sich Jonas Engelmann mit viel Kenntnis und Sympathie. Dabei geht es ihm nie nur um Musik, sondern immer auch um ihre Einordnung in soziale, politische und wirtschaftliche Hintergründe.

Ein Beispiel gefällig? Ich habe bislang immer geglaubt, in einem Musikstück ein Sample einer anderen Platte unterzubringen, sei eine Art Statement: Das Sample soll wiedererkannt werden und dient so dazu, dass der Künstler X seine Verehrung für den Künstler Y zum Ausdruck bringt, oder — die spannendere Variante — sich ein Statement Ys zu eigen macht, im Sinne von: Ich, X, teile das, wofür Y steht.

So war das wohl auch mal. Aber wussten Sie, dass Sampling mittlerweile zu einem blühenden Geschäftszweig geworden ist? Dass es sich für Plattenfirmen mittlerweile lohnt, Leute speziell fürs „Clearing“ von Samples zu beschäftigen, um ihren Einsatz rechtlich und kaufmännisch korrekt abzuwickeln? Dass für ein Sample berühmter Künstler, etwa James Brown, Marvin Gaye, Otis Redding oder auch Barry White (richtig, dem „Walrus of Love“) fünf- bis sechsstellige Dollarbeträge über den Tisch gereicht werden?

So krass war mir das nicht bekannt. Mir scheint mit dem Sample-Handel inzwischen eine Form der Zweitauswertung entstanden zu sein, die oft schon mehr Umsatz generieren dürfte als der Verkauf der ursprünglichen Platte (wobei das Sampling natürlich auch zur Vermarktung des Originals beiträgt).

Was tut sich da für ein merkwürdiger Widerspruch auf zwischen einerseits einem sozialen oder politischen Anliegen der Künstler und andererseits ungebremstem Kapitalismus? Oder ist es gar kein Widerspruch? Man schätzt da vieles falsch ein. Denn war nicht der ungebremste Kapitalismus schon immer Teil der Szene? Sollte jemand gedacht haben, ein Grandmaster Flash sei mal aus irgendeinem armen New Yorker Schwarzenghetto hervorgegangen, so entspricht das sicherlich dem damals in den Medien vermittelten Image. Weiß man jedoch, dass der Grandmaster schon früh über einen Fairlight verfügte, stellt sich seine soziale Situation doch ein wenig anders dar. Offenkundig gab es einen Riss zwischen dem projizierten Image und der Wirklichkeit. Und was ist heute von gerappten Anklagen, Empörungstexten und der damit angestrebten Street Credibility zu halten, wenn der Rapper (oder sein Produzent) in der Lage ist, Summen wie die obengenannten für ein simples Sample zu zahlen? — Ein interessanter Aspekt übrigens auch im Hinblick auf aktuellste Entwicklungen der Black Music.

Die weltanschauliche Theorie ist offenkundig das eine, aber wichtig ist aufm Platz. Da sind wir mitten drin in Jonas Engelmanns Themen und Thesen. Seine Positionen sind eindeutig, nicht immer leicht zu schlucken, aber meist wohlbegründet. Er untersucht Felder wie Außenseiter-Jazz (Sun Ra Arkestra, Matana Roberts, June Tyson), HipHop, Avantgarde (John Zorn, Public Enemy u.a.), die politischen Lieder eines Woody Guthrie, ein Konzert (oder sollte man sagen: das Konzert) von Aretha Franklin.

Alles dies nimmt Engelmann als kulturelle Statements ernst. Er schreibt, wie der Untertitel des Buches verrät, über Klangverhältnisse und Außenseiter-Sounds. Auf 130 Seiten bietet das Bändchen eine Sammlung von insgesamt 19 Artikeln, die zwischen 2012 und 2024 erstveröffentlicht wurden. Ein Blick ins Verzeichnis ihrer Herkunft lässt Rückschlüsse auf ihre Perspektive zu: Neues Deutschland, Jungle World, Freitag, taz, Ventil-Verlag (dessen Co-Verleger Engelmann ist), außerdem ist er Mitherausgeber der testcard-Buchreihe.

Jonas Engelmann geht an die musikalischen Wurzeln, er benennt gesellschaftliche Entstehungshintergründe, er spricht über Rassismus, Queerfeindlichkeit, Praktiken der Musikindustrie, er checkt die Quellen musikalischer Phänomene. Sein Buch ist voller Anregungen, denen nachzugehen sich lohnt (man staunt manchmal, was man im Web mittlerweile alles finden kann, wenn man einmal über die einfache Googlesuche hinausgeht). Und weil er zu argumentieren versteht, macht es Spaß, sich mit seinen Schlüssen auseinanderzusetzen, auch wenn man nicht jeden einzelnen unterschreiben möchte.

Jonas Engelmann:

Gesellschaftstanz — Klangverhältnisse und Außenseiter-Sounds

Verlag Andreas Reiffer, edition kopfkiosk Bd. 12

Meine 2025

ISBN 978-3-910335-12-7Verstörende Tiefe – ein paar einführende Worte von Lucy Mangan zu „Adolescence“ (Netflix)

„In den späten 80er Jahren gab es eine Trilogie von Dramen von Malcolm McKay mit dem Titel „A Wanted Man“. In den Hauptrollen spielten Denis Quilley und Bill Paterson, und im Mittelpunkt stand die phänomenale Leistung von Michael Fitzgerald als Billy, einem wegen grober Unanständigkeit verhafteten Mann, der des Mordes an einem Kind verdächtigt wird. Der erste Teil verfolgte sein Verhör durch einen Detektiv (Quilley), der zweite seinen Prozess und der dritte die Folgen. Es war und bleibt die erschütterndste und makelloseste Serie, die ich je gesehen habe – so nah an der Perfektion des Fernsehens, wie man sie nur erreichen kann.

Im Laufe der Jahre gab es einige Anwärter auf diese Krone, aber keine kam ihr so nahe wie Jack Thornes und Stephen Grahams erstaunliche vierteilige Serie Adolescence, deren technische Leistungen – jede Folge wurde in einer einzigen Einstellung gedreht – von einer Reihe preiswürdiger Darsteller und einem Drehbuch übertroffen werden, das es schafft, gleichzeitig intensiv naturalistisch und enorm eindrucksvoll zu sein. Adolescence ist ein zutiefst bewegendes, erschütterndes Erlebnis.“

Ich kenne „A Wanted Man“ aus den 80er Jahren nicht, und ich würde mich von Superlativen dieser Art zurückhalten, aber dass die Serie „Adolescence“ in Form und Inhalt Fernsehgeschichte schreibt und verstörende Tiefe bereithält, darüber habe ich nicht den geringsten Zweifel. Also, statt Lucy Mangans Besprechung des Vierteilers im Guardian (und englischen Original) „sicherheitshalber“ weiterzulesen, empfehle ich, ohne diverse, Schockwerte abmildernde, „Vor-Erzählungen“ auf den Abend zu warten, das Handy auszuschalten, und „Adolescence“ am Stück zu sehen. (m.e.)

„Grosses Leeres Land“

Parallel zu dem Songalbum „Luminal“ von Beatie Wolfe und Brian Eno erscheint am 6. Juni, als LP, CD, und DL, das Instrumentalalbum „Lateral“, mit der Komposition „Big Empty Country“: in der Vinyledituon heisst Seite A „Big Empty Country (Day), und Seite B „Big Empty Country (Night)“. Einmal mehr öffnet dieses Ambientwerk eine ganz eigene Atmosphäre, die zwar unverkennbar Enos Handschrift trägt, aber eben einen weiteren unerhörten Raum öffnet, insofern nur strukturell vergleichbar ist mit Grosskompositionen wie „Discreet Music“, „Thursday Afternoon“, „Lux“, oder „Reflection“. Der Titel „Big Empty Country“ ist mit Bedacht gewählt, und impliziert (mein ganz privater Höreindruck) sowohl das Unheimliche wie das Unberührte, das Pittorekse wie das Postapokalyptische. Der Klang der Gitarre, die hier und da ihre Spuren hinterlässt, ist pure Reminszenz ohne Nostalgie. Mehr wird nicht verraten. (m.e.)Once again, this ambient work opens up a completely unique atmosphere that bears Eno’s unmistakable signature, but opens up another unheard-of space that is only structurally comparable with major compositions such as “Discreet Music”, “Thursday Afternoon”, ‘Lux’ or “Reflection”. The title “Big Empty Country” was chosen with care, and implies (my very private impression) both the uncanny and the untouched, the pittoresque and the post-apocalyptic. The sound of the guitar, which leaves its mark here and there, is pure reminiscence without nostalgia. (m.e.)