Big Change Is Coming

„Revolutionäre träumen tagsüber. Sie träumen vorwärts und zwar gemeinsam.“

Da kann man nur hoffen, dass die amerikanischen Protestler in diesem Modus sind. Arcade Fire geht das nicht schnell genug. Die kanadische Band klagt in ihrem Song „Generation A“: „I can‘ t wait wait wait wait, I‘ m not a patient man…“ Neil Young, mein „hero forever“, schreitet durch eine verschneite Winterlandschaft mit einem Blockbuster unterm Arm und verkündet laut und stark: „BIG CHANGE IS COMING“. Wir hören täglich die Horrornachrichten aus der untergehenden „free world“. War die mahnende Stimme der Erzbischöfin während einer Messe, in der Trump sass, er solle sich mässigen, die singuläre Aufstandsstimme, die ein bisschen Hoffnung machte? Reichen die Aktionen der entlassenen Ranger des Yosemite Park, die die amerikanische Flagge kopfüber aufhängten? Ist es eine Option, die USA zu verlassen, was Cher überlegt? Ich bin ein Kind der Protestsongs. Viele der Musiker, die damals engagiert waren, leben noch. Alt und müde? Nun ja, sie treten noch auf: Bobby, Bruce, Joan, Joni… Sich still zu verhalten bzw. sich zu weigern, den Namen des Wüterichs in den Mund zu nehmen, reicht nicht. Ich bin gespannt, ob bei der Oscarverleihung heute Nacht Protest- bzw. Solidaritätskundgebungen stattfinden. „MASTERS OF WAR“ hätte Programm sein können. Bob Dylan wäre der Visionär geblieben. Nun heißt der Film über ihn A COMPLETE UNKNOWN. Man darf gespannt sein, ob „Der Brutalist“ gegen den Dichter gewinnt.

Neues von Brad Mehldau

Ein Freund schickte mir Ausschnitte aus dem Buch von Brad Mehldau „Formation – Building A Personal Canon. part 1“. What a pleasure to ready it.

“My first memorable strong connections to music were through the clock radio in my bedroom in Bedford. I got it for Christmas when I was seven years old, and I listened to the hits of that period. As I didn’t have a record player yet – that came a year later – I would hear a particular song, fall for it, then simply wait around until it was played again. I would try to catch it when we were in the car, when I was allowed to sit in the front seat and choose the station. The other place I would hear those songs was coming from the lifeguard’s transistor radio at our public swimming pool, where I spent many days in the summers of 1976-79. I got lost in them. I can still smell the chlorine and feel the hot cement and the warm sun when I hear those songs from that time. I can feel the sweet anticipation in my belly as they begin. I hear them now, and they’re like a good dream I’m recalling. There’s a sad kind of feeling of something that’s gone, but there’s an ache of happy yen all mixed up in it. There’s something that I can never get back, but here’s the thing: maybe I never had it. The first time I heard it, it was already like a dream – it was already beckoning me to somewhere that was better than here. The music showed me that place, but I could never really enter into it. So when I go and try to make music every time, I’m trying to crawl back into that dream. Even though I can’t, echoes of it remain everywhere in this world of action, and experiences add more colors to it, and soften or sharpen the hues that are already there. The dream and reality stand apart, but they’re wrapped into each other at the same time. Music is not so much the gift itself, but the slow, endless unwrapping of it, and a hint of what might be under the wrapping. What lies there is the Absolute: God. He is infinite; I am not. Music is both the expression of my finitude, and its consolation. I walk towards God in an asymptotic line, never quite meeting him directly. Yet there is evidence of this absolute, abiding presence here and now, in the music, every experience that informs that music, and every experience it informs in turn, in a perpetual exchange.” “My first time hearing Coltrane’s music was an initiation, and it was ceremonial, like an Indian sweat lodge. The cabins were hot during the day, and usually we would just stay outside during those hours when the sun peaked and find some shade. But Louis and I went into the cabin, and we shut the door and kept the windows shut. We sweated and listened to the Coltrane Quartet for about half an hour on his cassette player. When we emerged again from the cabin, I was changed. Sometimes music can do that to you. It raised the bar for my expectation as to what music could be. The intensity of the Coltrane was something I chased thereafter as a listener. Later on, when I became a jazz musician, it was the ideal when I played. The idea was to change someone’s perspective – really, to change their life – through your playing. If you failed, and you might fail most of the time, the effort itself was noble. Through my other cabin mate, Joe, who was a piano player like me, a year older, I discovered Jimi Hendrix. We listened in particular to the live album, Band of Gypsys.” “For me, it never felt like we were merely aping those greats as a means to an end. It was a way of moving towards my own sound. And, even if I was aping, it was so much fun. We were having this conversation about the music we loved – by playing it, with all our heart. There was a whole swath of us piano players who were trying to play like Wynton Kelly, the great hard bop pianist who graced so many important records of that era. Sometimes, someone would simply play a whole stretch of one of his solos, transcribed from a beloved record. Normally, that kind of thing would be frowned on, because it went against the principle of improvisation but, here, the fellow piano players who knew the solo as well would give assent and nod in approval. I did this with several choruses of Wynton Kelly’s solo on „No Blues“ from the Wynton Kelly Trio/Wes Montgomery record Smokin‘ at the Half Note. I still quote from that solo regularly. It’s a bedrock of joyous swing, melody and badassed fire all at once. Ditto pianist Bobby Timmons’s solo on „Spontaneous Combustion“ from The Cannonball Adderley Quintet in San Francisco. I wouldn’t be who I am without those solos. We pianists wanted Wynton Kelly’s crisp articulation but, more urgently, his feel. Your „feel““ in jazz parlance, means the way you sit in the swinging rhythmic pulse of the music, or you could say, where you sit, which part of the beat you lean into: the front end, the back end, somewhere in between, or maybe a shifting mixture of all of the above. Kelly laid in the back of the beat, and the way he swung was completely unique, and remains so in spite of being imitated by many. I can’t hear where he got that feel – I think it was something elemental in him – but you hear lots of pianists who grabbed onto it. Just listen to Herbie Hancock on his early Blue Note records, like Takin‘ Off. Kelly’s comping was influential on Herbie as well. People think of Wynton Kelly as an „inside“ player, but he was the first piano player in the small-group jazz setting to comp in a way that wasn’t part of the rhythm section grid. He paved the way for the more interactive comping that Herbie Hancock and others would take up after him – jabbing and interspersing stuff between the soloists‘ phrases, adding punctuation marks. It’s a common understanding that Miles called Wynton Kelly in for „Freddie Freeloader“ on Kind of Blue because he wanted something for that tune that was Blacker – bluesier and more swinging – than what Bill Evans could supply. That may be true, but it’s a backhanded diss to Kelly, because his comping was every bit as subtle as that of Bill Evans. Wynton Kelly dotted his eighth notes quite strongly, and in his own hands the effect was exhilarating; it has that joyous tension and relaxation all at once. It makes you want to move, and if you don’t dance outright some part of your body will be squirming happily. Yet in someone else’s hands that unabashedly and more often than his own model, Bud Powell. He often did that right in the middle of a pretty ballad and made it work, like on „If You Could See Me Now“ from Wes Montgomery’s Smokin‘ at the Half Note. It was never trite. Herbie, being Herbie, was able to fold Kelly’s influence into his own con-ception, which was already showing itself on Takin‘ Of. Many players, though, go for Kelly’s thing and it doesn’t work. It’s the sound of a relaxedness that no one else wants – like a guy who wears a muscle shirt when he’s a little too overweight to pull it off, and his tits stand out. This kind of unwelcome let-it-all-hang-out feel is a common jazz virus. The other problem is when you’ve got Kelly’s spirit well enough but you’re simply not as strong rhythmically, your touch is too soft, or your articulation not as crisp. It’s a flabby kind of playing Jazz fans and musicians alike complain about the „tightness“ of someone’s swing feel. Tight playing is certainly a phenomenon, but I don’t believe it’s due to some incurable lack of hipness, lack of sexual experience, or any of the other clichés one hears. Rigidity of swing is often rooted in lack of self-assurance. That may come from lack of experience and, further, a lack of proper technique. Technique gives one self-assurance because it provides physical relaxation. If you look at a tight player, you’ll usually see it in their body language. In any case, I started out corny and tight, and became less so as I gained technique and, with it, relaxation.” “When Wynton [Marsalis] played, it sounded like he knew what he wanted me to hear. It played well into his mission to teach listeners about jazz. That didacticism in the music itself was not available to me; in any case, I did not pursue it. It wasn’t that I didn’t care what the audience thought. Rather, the music unfolded in such a way that I only knew what I played after it happened. I couldn’t lead the audience anymore than to say: go out on a limb with me and let’s see where this goes. In some of the musicians I loved the most, there was also a feeling that they didn’t know where they would wind up, and that it might all just fall apart at any moment. In fact, my favorite moments were often when the canvas cracked and splintered, and the imperfection rose to the surface. There it was: the bare-assed exposure of a musician’s disfigured, true self. Yet that was no simple failure. It was the ambergris in the perfume, the smelly human underbelly beneath the handsome torso. It made the beauty more compelling. Vulnerability was not a virtue in itself. If someone always conveyed it, it became as insufferable as ceaseless impenetrability. Yet it could invite a listener towards self-forgiveness. Redemption-through-error was part and parcel of the improvisatory aesthetic itself. Beauty was indeed on display in the finished product, but just the endeavor to make beauty, to push past your own handicapped frailty, had beauty. I could lay my chips on that logic because it seemed to come from a primal, shared experience: When you were young, you had an aspiration. But then you damaged or broke something in your naive ignorance, for all to see. Someone showed you mercy, though, because that person had once shared your aspiration – they empathized with you – and you had dared to try. Your own failed effort was not only forgiven but it was preserved in the redemption. In musical terms, that meant that, if you fell on your ass on the bandstand in the search for beauty, it wasn’t necessarily a negative in the long run. I found that vulnerable feeling in musicians like Billie Holiday, Lester Young, Booker Little, Wayne Shorter, Chet Baker, and of course Miles. „The Buzzard Song,“ the opening track of Porgy and Bess, Miles’s collaboration with arranger Gil Evans playing the music from Gershwin’s opera, is a strong example. He delivers the opening doleful melody with such hesitancy. It’s so intimate because he has no defensive armor; his playing has this beautiful uncertainty to it. There is a risk in that kind of playing – what if you get burnt, what if you get laughed at? Here, I’m speaking mostly of a masculine phenomenon. As crazy as it sounds, when I arrived in New York, a lot of male aspirants like myself, depending on what they were bringing already from their background, shied away from ballads for that reason. Miles made it okay for other male musicians to show their ass and not just wag their dick. He was a model they benefited from, because he gave them a safe space for what was already inside of them. Listen to trumpeter Kenny Dorham’s plaintive solo on „Escapade“ his own masterful composition on Joe Henderson’s. Blue Note date, Our Thing. You hear doubt and foreboding even as hope tries to push through. When I hear playing like that, I experience kinship. Being vulnerable in the music, versus directly communicating it to someone else through words or actions, was appealing for me. My Cain was different, and maybe that was cool to a degree, but he was also secretly unsure. that lack of self-assurance was repellent to me in its outward manifestation socially, and inwardly in the self-loathing monologue going on between my ears. Yet, when I could express vulnerability in music in addition to the confidence that was already there, it gave me a more integrated version of Cain. On the one hand, there was the guy saying, „‚ve been cast out and I’m not sure who I am. But there was also the guy saying, „This is me – I’m going to pull you over into my tribe: just wait.“ I was both when I played, even if I couldn’t be anytime else. Miles showed the way. When „The Buzzard Song“ breaks into swing after the opening melody, he is unstoppably self-assured. He’s flipped the script. It’s all the more badassed because we already know who he is on the inside. He catches us off guard. His self-assurance is so much more interesting because we know it’s not all there is to him. It’s also a surmounting- he is the victor over his own doubt. The doubt he initially expressed becomes more compelling retroactively because we see it was a strong person who doubted. There is still a sense of foreboding, interlaid within the strength. This deep irony on the emotional level was only achievable by him through initially conveying weakness. That kind of expression was sexual for me when I heard it, sexuality sublimated in music. It was about showing something personal, passively, and then taking charge – all within one performance. I’m not sure if anyone will pull that off again like Miles. Vulnerably uncertain is not the only way to sound, especially not for trumpet players. Thank God that Freddie Hubbard was Freddie Hubbard through and through. The trumpet can swagger like nothing else. Still, something magic happens when that swagger is tempered by uncertainty. The rub between the two is what makes trumpeter Lee Morgan’s music timeless – Lee Morgan, the perfect jazz musician, if there ever was one. The blues was in everything he did, his rhythmic phrasing was always interesting and never locked in a grid. He had more swagger than just about anyone.” “It was the unspoken subject of the music. I don’t mean finitude of musical ideas. I mean finitude as our existential condition. Beauty is beauty because beauty is temporary, and beauty is temporary because we are temporary. Our mortality is the birthright that angels can never possess. To seek beauty was to seek an affirmation of life, even as you knew it wouldn’t last.” “Barry Harris was a model not just because of his mastery of a particular musical language, but because his melodic phrasing was so free within that language. Pianist Tommy Flanagan exemplified that as well. I was fortunate to hear Tommy several times in New York. His, dising in the latter years of his caret had reached a peak level of refinement, distilled in a beautiful trio setting with basist George Mraz and great trio drummers like Al Foster or Kenny Washington. There was always all this room in the music, room to breathe. To some, Barry and Tommy may have seemed bent on preserving a style that had passed, but that wasn’t true at all. By the time we arrived in New York, they had achieved poetic justice, if you had ears to hear. Bebop, as it was written on walls in the East Village, really was the „music of the future. Barry, far from being a throwback, was a Futurist for us. Barry’s teaching style was solidly didactic, but it was more compelling for us at that point than the frontal assault that Wynton was heralding uptown. Wynton advocated a return to authenticity, critiquing the development of jazz, as it began to draw outside influences like rock’n’roll into its expression. it was a global critique, in broad brushstrokes. Yet his music seemed no freer as a result. As vital and influential as Wynton was during that time, his music did not convey the mixture of looseness and profundity of any number of older musicians on the scene then. We wanted something we called „between the cracks.“ Barry and others had it. „Free“ had nothing to do with atonality or lack of structure. It was a feeling, not a dictum. It was either there in the music or it wasn’t.” “Like all those kinds of designations, Americana was a term that appeared after the music had already come into being. It was a sound you could hear already in Charlie’s contribution on Keith Jarrett’s 1975 ECM record Arbour Zena, and I got a little taste of it a few years later when I played and recorded with Charlie on his album American Dreams – you can hear it strongly on the opening title track. The way I would describe Americana is that whatever it reminds you of depends on music you already knew, the common link being a North American source (thus including great Canadian artists like Neil Young, most of the members of The Band, and Joni Mitchell). For me, the sound of „American Dreams“ – the harmony, the spaciousness – was connected to Aaron Copland in a piece like Appalachian Spring. Ironically or not, a lot of the Americana music I discovered in my Bildung was released by a European producer, Manfred Eicher, on his ECM label. It may have confirmed the truism that one sometimes sees what is special about a culture when looking at it from a distance. In any case, we can all thank Manfred for documenting so much great music. Another musician who influenced me greatly was Keith Jarrett, and, while I hesitate to assign genres, no matter how pliable, to any of these great figures, Keith’s solo output spoke to me in a similar way. The first record I heard from him was the triple-LP set Bremen/Lausanne. It was a birthday gift I received from Dylan, of all people, that last summer of our tumultuous friendship, and it immediately changed my take on what was possible in music, in the same way that the Coltrane with Louis in Merrywood had the previous summer. I had heard a fair amount of jazz by that time, but this was something different. I initially connected Keith’s solo output on records like Bremen/Lausanne, Staircase, and The Köln Concert(…) There were all these lines you could draw between artists who were on the face of it very different in their designs, but the thread was emotional, and the emotion was often something like nostalgia, home and hearth, melancholy at times but, under all of that, quiet, abiding joy. It was like some kind of unspoken secret they were telling me about myself, and about whom I could become as a pianist, whether it was the sturdy weaving of George Winston, the busking arpeggios of Billy Joel, the wistful boogie-woogie of Guaraldi’s „Linus and Lucy, or the exalted vistas that Keith Jarrett reached. I remember that, after I had been listening to the first side of Bremen/Lausanne for weeks, one evening I sat down to play on our Sohmer spinet in West Hartford, and something came out of me that was inspired by Keith’s playing, something that seemed to have come from nowhere in terms of preparing for it in any way. It had that feeling of time traves got from the fantasy and science fiction I was reading – that large, endless scope – because what Keith inaugurated in those solo recordings was improvised music on an epic scale: music from one person alone that journeyed widely in one sitting, full of turmoil, joy, and mystery. It was a powerful experience, and I would meet it again a couple decades later at the beginning of my thirties, when I began to speak my own solo voice. Solo piano for me has always been just that – solo- in terms of a certain courage one must have to make a solitary improvisatory journey, with no companions. That is both its romance and its challenge.” “With Pat, the sublime was just as much a physical feeling. As his solo continued, I had the sensation of something overpowering welling up in my stomach and then emanating outwards towards my heart and through my whole body. I experienced that same welling years later when our first child was born, and I was there to see it. On that solo, Pat ran his guitar through a Roland GR-300 guitar synthesizer, and the wailing sound he got was like nothing else. It pushed its way immediately to the front of the top ten of my air-guitaring list, in a tie for first place with Hendrix’s „Machine Gun.“ … EXCERPTS FROM BRAD MEHLDAU’S NEW BOOK OF REFLECTIONS ON BEING AN ARTIST

Heroes never die

In dem Sonderheft vom RollingStone erschien im Januar eine Liste der besten Gitarristen. Weil meine Gitarrenheroes schlecht dabei wegkamen, erklärte ich mich nicht beleidigt wie damals Prince, der nicht berücksichtigt war. Ob es eine Bestsellerliste ist oder ob es eine Bestenflussreichste Liste ist, zeigte sich später bei Prince, der etwas später ganz vorne lag. Jedenfalls sind für mich Jimi Hendrix, Duane Allman, Keith Richards, Pete Townsend, Mark Knopfler und Joni Mitchell hervorragende Gitarristen.

Wenn mir ein Gitarrist verklickern wollte, dass er- Barbie mässig – mich erobern wolle, dass er nur für mich singt und spielt fände ich das charmant, würde ihm aber dafür nicht mein Hab und Gut überlassen. Das nennt man scammen. Hier auf der Insel lebt eine Frau die auf einen Scammer reingefallen ist. Sie hat ihm ihre Finca überschrieben und weg war der Schurke.

Martina Hefter hat über dieses Thema ein Buch geschrieben Hey guten Morgen wie geht es dir?lautet der Titel. Es ist – um genreübergreifend zu bestsellern – mit dem deutschen Buchpreis 2024 ausgezeichnet worden. Ich mag Bücher,die aktuelle Themen aufgreifen,hier wird also der Umgang mit LoveScammern thematisiert. Das Spiel mit der Wahrheit gegen die Lüge liest sich so gut wie ein spannendes Fußballspiel.

Es käme nicht ganz zuvorderst auf meiner Bestsellerliste, da steht schon eine Weile ein Buch,das meine philosophischen Heroes beschreibt : Paul Feyerabend,Susan Sontag,Adorno. Die Geister der Gegenwart. So heißt auch das Buch von Wolfram Eilenberger.

Fly me to the moon, let me play among the stars.

Bei den diesjährigen GRAMMYs fand ein Clip mit einem hinreißenden Auftritt von Cynthia Erivo meine Aufmerksamkeit. Die sehr emotionale Performance dieser exklusiven Sängerin war eine Hommage an Quincy Jones, der im vergangenen Jahr verstorben ist. Erivo wurde von dem 77 jährigen Herbie Hancock am Klavier begleitet. What a joy to listen to such a great voice and musican . Das Original “ Fly me to the moon“ wurde von Bart Howard verfasst. Frank Sinatra sang eine Swing Version, die Quincy Jones arrangiert hatte. Es war in der Zeit, als Apollo zum Mond geschickt wurde. Cynthia Erivo sang sie als Erinnerung an Quincy Jones. Just great.

Die big glammour Show hat ja doch zwischendrin hõrenswert Verstecktes von höchster Qualität. Man muss es nur entdecken. Wer den großartigen Clip noch nicht gesehen hat, findet ihn ziemlich weit hinten auf HTTPS://live.grammy.com

Nikolauswünsche von Lajla:

01. Alles von Jackson Browne

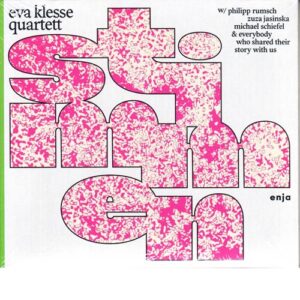

02. Eva Klesse Quartett, Stimmen

03. Reba Mc Intyre, Consider me gone

04. Lainey Wilson, Country ist cool again

05. Carrie Underwood, Before the Cheats

06. Miranda Lambert, I ain’t in Kansas City anymore

07. Willie Nelson, Last leaf in the tree.

08. Einstuerzende Neubauten, Rampen

09. Jeff Parker, The way out of easy

10. Und immer Anton Bruckner, Te DeumYou can always come back, but you can’t come back all the way

Diese Zeilen aus Bob Dylans Song „Mississippi“ sind bezeichnend für seinen Auftritt gestern in Düsseldorf. Wie kann er seinen langweiligen Auftritt vor 7.500 Gästen legitimieren? Braucht er die Einnahmen von 7 Millionen? Für was? Es ist nicht interessant. Er kommt in seiner Cloud, hält sich am Piano fest und seine gute Band überspielt galant seine Notenpatzer. In dem Dimmer Wohnzimmerlicht erkennt man ihn eh nicht, ja, aber hallo, das ist doch Dylans voice, überall sind Mischpulte, wahrscheinlich auch an der Decke. Er singt unverkennbar, 1 Stunde 45 Minuten und nie kam mir ein Konzert langweiliger und never ending vor. Freiwillig wäre ich nicht hingegangen. Es war ein Geschenk. In Bad Ischl, der diesjährigen europäischen Kulturhauptstadt spielt Hubert von Goisern, der aus der Gegend kommt und den ich sehr verehre, unangesagt jeden Abend in irgendeinem Club. Man darf immer davon ausgehen, dass es ein sinnliches Musikerlebnis sein wird. Diese Garantie bringt Bob Dylan nicht bzw. nicht mehr. Von manchen Konzerten hört man schwärmerische Kritiken, weil er doch tatsächlich mal gelacht hat oder sich am Ende bedankte. Wow! Joni Mitchells Auftritt vor zwei Wochen war auch nicht das ganz große Musikerlebnis, immerhin singt sie noch ganz passabel Neues und freut sich zusammen mit ihren Fans. Große politische Statements hat sie nie gesungen, aber eben Bob Dylan. A hard rain oder Masters of war sind meiner Meinung nach ein Must Sing in dieser wackligen Weltlage. OK. Er war da, er kann nicht mehr den ganzen Weg gehen. Das konnte man sehen und hören.

Peace.

Women.On.Fire.

she wanted to be a blade

of grass amid the fields

but he wouldn’t agree

to be a dandelionshe wanted to be a robin singing

through the leaves

but he refused to be

her treeshe spun herself into a web

and looking for a place to rest

turned to him

but he stood straight

declining to be her cornershe tried to be a book

but he wouldn’t readshe turned herself into a bulb

but he wouldn’t let her growshe decided to become

a woman

and though he still refused

to be a man

she decided it was all

rightby Nikki

Jackson Browne

„A Human Touch“ zum Beispiel: „Everybody get s lonely / Feel like it s all too much / Reaching out for some connections / or maybe just their own reflection / Not everybody finds it / Sometimes all anybody needs / IS A Human Touch“

Es gibt sie noch, die Texte zum aktuellen Zeitgeschehen, sogar musikalisch unterlegt. Ich entdeckte sie im Austin City Limit TV, wo ich mir einen Auftritt von Jackson Browne anschaute. Die Lyrics kommen aus seiner Feder. Er trat mit der Sängerin Leslie Mendelssohn auf, übrigens eine spannende Neuentdeckung für mich. „A Human Touch“ ist ein wunderbar weich gesungenes Lied, sie schrieben und sangen es zusammen für einen Film. Auf dem Programm stand noch ein anderer Song, den Jackson den Kindern von Immigranten gewidmet hat: „The Dreamer“.

Just a child when she crossed the border / To reunite with her father / And with a cruxifix to remind her / She pledged her future to thls land / And does the best she can do / A dónde van los sueños…

Das ist ein Gänsehautsong. JB knüpft an die Traditionen seiner Songwriterfreunde an, die in den 69ern begannen über Proteste, Tod und Kriege zu singen: Bob Dylan, CSNY, Joni und Joan – was für glory times!

Jackson ist ein brillanter Songwriter, ernst und immer mit der Zeit gehend. Er kann aber auch lustig sein, wie er in „Red Neck Friend“ über einen Penis albert. Oder ganz laid back in „Take It Easy“. .Damit hatte er seinen Durchbruch, obwohl der Song für die Eagles war. Für die Kinks schrieb er Waterloo Sunset, das wusste ich gar nicht. Ich habe leider Jackson Browne nie live gesehen. Vielleicht klappt das ja noch, er tourt noch immer.

Meine Songliste ist lang, sie ist seit über 40 Jahren gewebt:

These Days

The Pretender

Too late for the Sky

Here come the tears again

I am alive

Missing Person

Song for Barcelona(oder überhaupt das ganze Album, das er in Barcelona mit dem wunderbaren David Lindley gemacht hat)

Big Sister Taylor Swift in the Neighborhood

Was bitte macht Taylor Swift in Gelsenkirchen? Falsche Frage! Was macht sie aus Gelsenkirchen, der ärmsten Stadt in Deutschland? Sie verwandelt das „Shithole“, wie es die englischen Fans während der EM nannten, in ein singendes, glitzerndes Swiftkirchen. Miss Americana gibt dem Pott die Ehre, die Arena wankt wie in Assauers Bestzeiten. Was geht da auf Schalkes Terrain ab? Die große Freundin ist gekommen, und ihre tausenden Freundinnen besuchen sie. Ihre Swifties waren fleissig, haben das Outfit mit Pailletten und Glitzer genäht, sie haben Cowboystiefel bei dieser Hitze übergezogen und natürlich ist ihr Mund blutrot angemalt. An den Armen hängen viele Freundschaftsbändchen, die ihre Big Freundin mit LED Lampen versieht, damit ihre Fans auch in der Nacht zu dem grossen Friendshipevent finden. Auch ich spüre die kõrperliche Nähe einer mir unbekannten Freundin, die mir lächelnd ein Bändchen überreicht. Diese so hergestellte Nähe ist ein wahrer Kunstgriff, der die anonymen bleibenden Followerfriends ins Abseits stellt. Die Zahl 13 steht auf Stirnen oder Handgelenken, big sister was born on the 13th of Dezember. Auf meine Frage an die Fans: was gefällt Euch an Taylor Swift, kommt nie als Antwort, sie sei eine geile Frau oder ähnliches. Immer antworten sie: ihre Musik, ihre Lyrics. Es ist schon phänomenal, wie die meist sehr jungen Mädels die Texte singen können. Überall in der Innenstadt stehen Boxen mit jungen Fans, die die Songs wiedergeben. Alle singen mit, egal ob sie die Currywurst gerade quer im Mund haben oder nicht. Ich setze mich in ein Café und denke über die Sinnlichkeit in der Popmusik nach. Nicht vorstellbar, dass wir uns wie Bob Dylan oder Neil Young oder Joni Mitchell verkleidet hätten. Nur wenige konnten die Texte dieser alten Heroes mitsingen. Dass die Swifties das können liegt an den Videos auf YouTube, die alle Texte zum Mitlernen anzeigen. Das ist ein anderer Kunstgriff von Taylor, sich ihre Fans zu angeln.Und die Lyrics sind gut. Sie hat immerhin einen Ehrendoktor von der Universität in New York erhalten. Auch in unseren akademischen Breiten hält der Medienwissenschaftler Jõrn Glasenapp der Uni in Bamberg eine Vorlesung über Big Sister. Der Philosoph Eilenberger sagt in seiner Sendung Sternstunde der Philosophie über Taylor Swift am Ende: Warum wird sie nicht der neue Präsident der Demokraten. Taylor ist nicht politisch, sie ist bestenfalls eine engagierte Feministin und klar gegen Trump.

Mein Lieblingssong ist übrigens „The Lakes“. Da singt sie zu schöner Melodie über den Lakedistrikt und die Dichter, die dort starben. Ich habe immer einen Band von Wordsworth dabei, wahrscheinlich mag ich deswegen den Song. Er ist als Appendix des Albums FOLKLORE zu finden.

Hätte ich nur 5 Minuten Zeit gehabt, Frau Swift zu fragen, weshalb sind sie in die ärmste Stadt Deutschlands gekommen , spielen gleich drei Konzerte, für die Sie 100- 700 EU Eintritt verlangen? Ich denke sie hätte geantwortet: I promise, I soon come again.

Identität und Fußball

“ Wer bin ich?“ Ist die dauerwellige Modefrage nach der Identität. In den 60 er Jahren fragten wir uns weniger nach unserem Ich sein, uns interessierte mehr “ Was wollen wir?“ Wir wollten Steppenwölfe sein, wir waren geboren, um wild und frei zu sein. ( Der Film „Born to be wild“ kommt ab Donnerstag in die Kinos).Wir wollten Gerechtigkeit und waren gegen Atomkraft und Krieg. Bei der schwierigen Frage nach der eigenen Identität tut sich die Generation X mit den Eindeutigkeiten für das Ich sehr schwer. Das Gendern scheint als Geländer notwendig zu sein für die Haltung auf einer gleichberechtigten Lebensbühne.

Die Frage nach einer nationalen Identität kam mir gestern während des Spiels Portugal gegen Slowenien. Da identifizierte sich eine ganze Nation mit einem einzigen Spieler : Ronaldo. Dass diese Last für einen Einzelnen nicht zu tragen ist, zeigte sich in seinem Scheitern beim 1. Elfmeter. Ronaldo war verzweifelt, Tränen flossen. Als sich beim Elfmeterschießen die ganze Mannschaft um einen Sieg bemühte, kam Ronaldo ’s Identität, die sich durch Stolz, Stärke und Können auszeichnet zurück. Die Weitergabe des Helden an den neu gekürten King of the game, der portugiesische Torwart hielt gleich drei Elfmeter, war rührend mit anzusehen. Hier zeigte sich besonders schön, dass der Zusammenhalt wichtiger ist als die trendige Frage nach dem Selbst.