„future fantasies from a shadow world long gone“

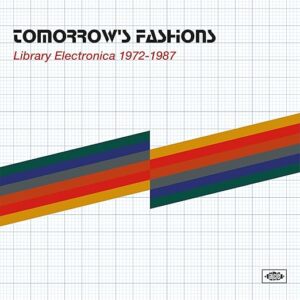

Bob Stanley (St. Etienne) did it again. A master of modern day theme albums with twists and thoughts. „Nothing said new or modern or futuristic quite like a synthesiser in the 70s and 80s. If you were shooting an advert and you wanted your product or your company to appear forward-thinking and ahead of the game, then you would want something electronic, something out of the ordinary.“ Let‘s enter the workd of ancient „library music“ with a brilliant compilation. Even Mike Ratledge and Karl Jenkins from Soft Machine sometimes operated from the shadows…this is a sophisticated work with in-depth notes on all the music you get to hear.

„Tomorrow’s Fashions (Flowworker’s August relevation from the „archive“) is sequenced with care so it’s a linear, satisfying listen. It is not a pot-luck grab bag. The opening track is Simon Park’s “Coaster” (1982). With human drums, it glistens, is gently funky and exhibits a mind-set close-to the roughly contemporaneous Human League instrumental “Gordon’s Gin.” The earliest track is Sam Spence’s “Leaving” (1972). It pre-figures what Jean-Michel Jarre would be up to; considering this, it’s spooky that Spence had studied at the École Normales de Musique de Paris. “Leaving,” with its bargain-basement Tangerine Dream vibe, also ended up as a German single in 1973. Any such external musical connections with this material are, of course, imputed, implied, but a prime goal of library music was to tap into and co-opt current stylistic zeitgeists. This is how it would get to be used. Take Rubba’s fantastic “Space Walk” (1979), which is along the lines of both Jean-Michel Jarre and Space (the French synth-disco combo, not the Liverpool band). While the endlessly fascinating Tomorrow’s Fashions – Library Electronica 1972-1987 deftly opens the door on what’s been a less familiar aspect of library music which aesthetically ripples through recent-ish labels like Ghost Box and Warp it also, perhaps more importantly, confirms that while these composers and musicians operated out of the public eye without any recognition, they did draw from the wider world. The music itself proves this, that these often shadowy figures and their creations were no further from the latest flavours in popular music than what was on sale at the high street’s hippest record shops. How extraordinary it is, then, that what’s heard here has taken four or five decades to reach today’s retail outlets.“

(Kieron Tyler, TheArtsDesk)

Ein Kommentar

Kieran Tyler

Mitte der 1990er Jahre stieg das Bewusstsein für das Phänomen der Bibliotheksmusik, parallel zum Trend des Easy Listening. Die Beschäftigung mit musikalischer Esoterik erreichte einen bis dahin unerreichten Höhepunkt. Zunächst war es das groovige, swingende Material, das auf Compilation-Alben landete. Komponisten/Spieler wie Alan Hawkshaw, Keith Mansfield und Alan Parker wurden zu bekannten Namen.

Library-Alben wurden für hohe Summen gehandelt. Schnell entdeckte man noch seltsamere Aufnahmen: Kuriositäten aus dem Bosworth Music Archive, Material des experimentellen Jazz-Komponisten Basil Kirchin. Man fand heraus, dass Jimmy Page und The Pretty Things für Bibliotheksorganisationen aufgenommen hatten. Es gab französische Firmen, die das produzierten, was man streng genommen als „Produktionsmusik“ bezeichnet. Auch italienische.

Diese verborgene Schattenwelt brachte eine scheinbar endlose Menge an Musik hervor, die es zu entdecken galt. Der eigentliche Trick besteht jedoch darin, ihr eine Form zu geben. Eine Erzählung zu finden.